Pop in the Anthro-po-scene

12.02.14

In my early days studying creative writing, I was required, as most of us were at some point, to take a workshop outside my primary genre. I chose fiction, and if you’re ever up for a laugh, you should corner me and ask me to read aloud my terrible stories of untimely pregnancies and people losing limbs in grisly car accidents. My stories received much criticism, most of it warranted, but there was one criticism that always stuck with me as being somewhat ill-conceived.

In my early days studying creative writing, I was required, as most of us were at some point, to take a workshop outside my primary genre. I chose fiction, and if you’re ever up for a laugh, you should corner me and ask me to read aloud my terrible stories of untimely pregnancies and people losing limbs in grisly car accidents. My stories received much criticism, most of it warranted, but there was one criticism that always stuck with me as being somewhat ill-conceived.

From what I can recall, my story featured quite a bit of consumer products, all referred to by name, very much in the vein of Douglas Coupland’s 1992 novel Shampoo Planet. I could understand a criticism of these brand names as being awkward and not central to how the story was operating in the world it had created for itself. The criticism I received, however, was that specific pop culture references would date my work. In other words, I was writing something that was disposable and would never have the potential of achieving the realm of the “timeless,” which apparently was a desirable goal.

##############

Almost ten years later, in April of 2011, poet and educator Rachel Zucker proposed the following question to readers of the Poetry Foundation’s Harriet blog: “Is it more important to you that your poems be timeless or timely and why?” Zucker received quite a few responses, but the one that stands out to me is a piece written by Kwame Dawes. In it, he asserts that

the quest for timelessness […] is arrogant because it grows out of a desire to be read by people long after we have left this earth. [… It] is a quest for immortality. […] Sadly, such an effort is likely to generate […] not great work, but [work that is] mediocre and ordinary.

Dawes concludes that the best way to go about writing poetry (at least for himself) is to “write for the present moment as fiercely and as beautifully” as possible. While I find the term “beauty” a rather loaded word, I think most would agree that a focused assertion of one’s writing abilities in the moment makes it more likely that higher quality work will be produced. Calculating the future “value” of a poem during composition seems like it would open one to the risk of self-censorship, at the very least.

##############

The term “Anthropocene” has been in use since the early 2000s, when Nobel prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul J. Crutzen and biologist Eugene F. Stoermer began to use it to describe a new period of the Earth’s geological history in which humans have come to shape natural forces. In the article “Learning How to Die in the Anthropocene,” Roy Scranton notes that a laundry list of scientists have come to agree that we have passed the point of no return in respect to global warming and that “the question is no longer whether global warming exists or how we might stop it, but how we are going to deal with it.” Scranton believes this reality leads us to one hell of a philosophical end point: “understanding that this civilization is already dead.”

The Anthropocene, by extension, implies that poetry can no longer have the grand claim to being timeless; nothing can make that claim in light of the Earth’s accelerated and certain decline. What goal can any of the arts have now but to be entirely of the moment?

##############

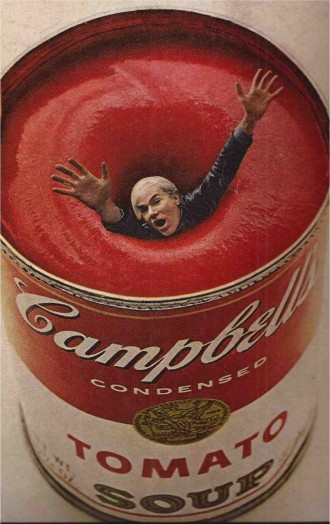

Over the years, popular culture has frequently found itself shoved into the academy’s “low-brow” box, a gesture that spawned an entire art movement, valuable volumes of cultural criticism, and the founding of one of the first departments of popular culture studies at BGSU in 1973. The “low-brow” categorization certainly operated in unproductive ways, too, which led to comments like the one I experienced with my terrible story. In circumstances like that one, pop is rejected because it is seen as fleeting and of the moment. It’s seen as something that will not have a long shelf-life in terms of cultural memory. But in the face of a civilization that is already dead, isn’t cultural shelf-life kind of a moot point?

##############

In 1997-1998, a “Super El Niño” wreaked havoc on communities and caused (at that point in time) the warmest year on record. It even made its way onto SNL. The natural becoming a pop event.

Shortly after the events of El Niño, a book entitled Real Things: An Anthology of Popular Culture in American Poetry was published by Indiana University Press in 1999. This anthology seems to address pop-as-subject, not necessarily pop-as-material, but the title alone announces a growing and serious literary interest (these things are real!!!).

Chelsey Minnis’s first book Zirconium is published by Fence in 2001. And while gurlesque isn’t 100% pop, its riot grrl influence is notable in that it is used as material/substance, not necessarily as subject matter (counterculture made pop through its usage as ready-made, culturally-charged material).

I’m not arguing that El Niño is the cause of a rise in pop language gestures, but I find it interesting that a growing concern directed toward global warming coincides with a more visible embrace of pop aesthetic within the literary community.

##############

Today, in 2014, we see a pop aesthetic thriving in the poetry/lit scene at a time where we (artists and academics, at least) have more or less accepted the fate of the planet and our civilization. The crafted pop-slacker lyrics of Ben Fama’s Aquarius Rising very much toy with the dichotomy of the high-brow/low-brow. Lara Glenum’s Pop Corpse, a playground of abject sex-barbie-mermaid-deathflesh, is complex in its theatrical pageantry, which distances readers into a serious consideration of the implications of all the shit, glitter, and hashtags that parade before their eyes.

Kate Durbin’s work blurs the line between the conceptual and the transformative by using language as a device to divorce reality show scenes from their highly-produced filmic roots. Her work takes on an added dimension in performance, where in a very pop gesture she repurposes her own pieces to create a live, remediated (and often interactive) experience.

And a poem like Andrew Durbin’s pop-epic “Next-Level Spleen” is ambitious in its conversational, Clueless-inspired consideration of Baudelaire. Once, during Durbin’s performance of this piece, a widely anthologized poet threw a tennis ball at him, which I think speaks more to the timeliness and success of the poem, rather than some sort of rotten tomato gesture. Only a powerful, culturally-relevant poem could reduce someone of such stature to a petulant state. Perhaps it was a harrowing realization that the notion of the “timeless” poem could itself be a thing of the past.