One Prism of History: On Desire and Secrecy in Wendy Ortiz’s Excavation: A Memoir

22.12.14

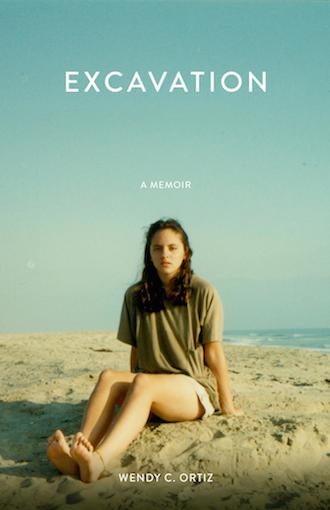

Exacavation: A Memoir

Exacavation: A Memoir

by Wendy C. Ortiz

Future Tense Books

242 pp / $14.95

“Don’t eat a beefsteak. If you do the eyes of that cow will pursue you through all eternity.” – Joyce, Ulysses

“If I maintain my silence about my secret it is my prisoner…if I let it slip from my tongue, I am ITS prisoner.” – Schopenhauer

Wendy C. Ortiz’s Excavation: A Memoir chronicles two interconnected acts of discovery: the book details a young Ortiz’s relationship with her teacher, an older man who claimed to see her as a writer and woman in ways her parents and peers did not. Echoing this story of a painful, dysfunctional relationship is that of Ortiz’s present self, attempting to reclaim language and experience by telling it.

One afternoon when I was eighteen, I walked into a tattoo parlor in downtown Nashville and got the phrase “Fear no more, says the heart.” inscribed below my left breast. Hours later, I proudly showed my 12th grade English Teacher, who had written her dissertation on Woolf and exposed me to Mrs. Dalloway months before I – uninvitedly, I should add – exposed my ribcage to her.

My relationship with my high school English teacher was certainly not an erotic or sexual one, but I did romanticize it in a manner not dissimilar to that described in Excavation. Like its narrator, I was a private person. I craved recognition from teachers and adults I perceived as intellectual, wise, or representative of a sophisticated world that might one day deliver me from my own. What made me lonely made me lonely. I don’t remember exactly at what point I decided or was given the idea that it might also make me special, artistic, intelligent – but it is still one I cling to, however lame or juvenile or weak. Just this morning, I cried in my boyfriend’s shower and softly repeated Ortiz’s words in a random instant of some own placeless, illogical loneliness of my own. There are always those impossible things we still want, aren’t there?

Excavation’s narrator’s relationship with “Mr. Ivers” begins with a similar convergence of recognition and desire. Shortly after Ortiz’s eighth grade teacher praises young Wendy’s writing, his compliments take on a primarily sexual dimension. As 21st century readers, able to Google the author’s personal history on our phones without even closing the book, I think one of the greatest challenges with memoirs is the temptation to pay attention to the wrong parts of the story: to crave “closure” and fail to recognize subtler aspects of the book than “what happens” to its characters. Excavation offers us a salacious and profoundly engaging story, but it is not a simple or moralistic one, condemning “Mr. Ivers” in order to elevate its author and protagonist.

Instead, Excavation tells a difficult, delicate story about desire that is human, always fallible, and often excruciating. As much as it is a story about love or self-discovery, it is also a story about secrecy. Why do we keep secrets? What do we risk or gain by keeping them or giving them up? I return to Mary Ruefle – this time on secrets – who reminds us: the origins of poetry are clearly rooted in obscurity, in secretiveness, in incantation, in spells that must at once invoke and protect, tell the secret and keep it, of the astronaut who said Sometimes you get the feeling the universe is trying to prevent us from discovering the truth.

“For as long as I could remember, there were secrets I found myself weaving with a lover or potential lover, man or woman, the co-conspiratorial air that forced such strange intimacy,” Ortiz reflects in a session with a Jungian analyst years after the affair. I found this, the accounts of Ortiz’s rituals of compulsive secret keeping, one of the most provoking and relatable aspects of the book. The act of weaving carries with it a rich history that is both literary and distinctly female. Scheherazade intricately weaves stories, fending off her death at the hands of the king and ultimately wooing him.

So, female authorship is mythically linked to the secret cultivation of desire as a means of survival. The craft of storytelling becomes means to fend off consumption, a way out of the paradigm of appetites. In “Laestrygonians,” Joyce’s Leopold Bloom wanders the city, famished and somewhat paralyzed by his hunger and revulsion at the devouring male image, unable to chose between famine and cannibalism. In other words, is it better to starve or survive by becoming a monster? If, like Leopold Bloom, the male literary narrator is always (or even, often) asking himself eat or be eaten, female language comes into being under this ever-present threat. The female voice is always distractive, is always under threat of extinction.

Ortiz writes of language and history as forces containing her within trauma and holding the possibility of a self freed from it:

The history I write is just one prism of history, a place where a part of me feels trapped in time. In my ancient history, a man arrived as my junior high teacher and metamorphosed into someone I would timidly think of as my lover.

The fossils of a woman have been found in the La Brea Tar Pits. The “La Brea Woman” is about 10,000 years old. The La Brea Woman is thought to have been between the ages of 17-25 when she died. Someone unearthed her, freed her body from the bitumen.

I watch people holding the black fence that keeps them from losing themselves in the lake of muck. We do not want to become part of the ooze primordial. An ooze that lives on…

The La Brea Woman is long dead but lives on in a display, along with a variety of creatures. They perished in a tar that also preserved them.

The display is how we tell the story.”

The act of excavation suggests salvage, retrieving something that would otherwise remain buried and ultimately be lost. However, I would like to argue that Ortiz is doing something more than preserving her own story: she is altering its very substance, creating it anew. Though language cannot bring us back to what we have left or has left us, its creation breathes life into otherwise unspoken existence. There are always those impossible things we still want, aren’t there? Our words form worlds that that we can belong to, create tribes that otherwise would not exist. Secrets do not dissipate when we speak them; they flower into the atmosphere and we breathe them back in, and out, and in again. The display is how we tell this story, but it is altered – and alters – with each telling.