Against the Narrowing of Language: On Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout

06.02.18

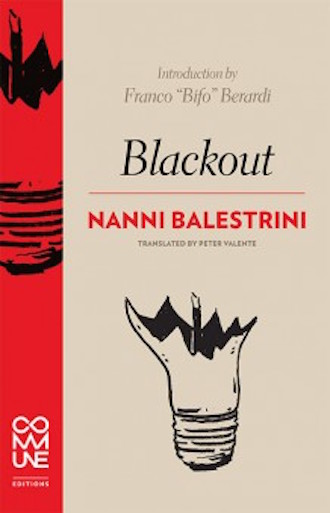

Blackout

Blackout

by Nanni Balestrini

Translated by Peter Valente

AK Press

$16 / 80 pp.

“Dancing in the Street” by Martha and the Vandella’s was an anthem of the youth movements in the emergent New Left. Martha called the children of the world out onto the street in celebration and protest. Blackout by Nanni Balestrini imagines a power outage in a city like New York as an opportunity for significant social change.

When the lights went out on July 13, 1977, New York City entered a place it had never been before. Throughout the power outage, there was looting, but there was also a sense of excitement and community. The New York Times ran a photo of Mother Bucka’s Ice Cream Parlor in Greenwich Village. Employees shoveled out cones by lantern light and the prevailing mood was one of joy. A blackout is one of the rare moments that can generate a total rupture. It’s a rare happening, an event in itself. Chicago Surrealist Franklin Rosemont described this experience in his memoir, Dancin’ in the Street: “Recognizing that certain rare moments in our lives radiate wonder, excitement, curiosity, and pleasure…we maintained that the central aim of poetry was to multiply those moments of perturbation and thus to create the conditions for a new (poetic) way of life for all.”

Nanni Balestrini was a revolutionary poet and activist in 1960s Italy. He was a founding member of the Gruppo 63, which eventually came to be called Neovanguardia, a group of artists and activists that spearheaded the carnival and parodying spirit of 1968 in Italy.

Through a rare alignment of progressive history, this party joined with other workers movements to form a governing coalition, before being chased out by reaction. Balestrini wrote poetry using cutup newspapers and found objects. He experiments in the modern tradition of combinatory poetics and the poetry of headlines, or the feiulleton.

At the turn of the 20th century, newspapers began including feiulleton or fait divers. These were brief accounts of happenings. Their breathlessness captured the spirit of acceleration and mass media. Many modernist luminaries spent years contributing these kinds of accounts including Robert Walser, Felix Feneon, Milena Jesenka, and Roberto Arlt. Balestrini used this method as a way of commenting on the strangeness and excitement of the events of the day, even as he influenced the course of these events.

In 1969, the Italian student worker’s movement effectively partnered with labor organizations, in a moment called “Hot Autumn.” This led to the establishing of a coalition government between several leftist factions Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua officially bringing in an era of operaismo and later autonomia government. Ideologies founded in an emphasis on governance through worker’s councils. Blackout is interspersed with the comedy and the cynicism of ten years’ worth of political experience and frustration.

For many, these years are often called the “Lead Years.” Lead from the bullets, or the sense of stalled progress, but as Bifo Berardi mentions in the introduction to Blackout, the violence of the era was stylized, symbolic. Today the violence in Italy is more pervasive. It percolates daily behavior, “in labor relations, in the rising tide of feminicide and child abuse, and in the waves of political hatred that never becomes open protest, never deploys as movement, but flows through the folds of public discourse.”

Balestrini’s experience with politics represents the frustration of modernism, and the New Left in the face of something never quite arriving, and in the face of the emergent new order. And as an activist poet of a named avant-garde, and an actor within a social protest movement, Balestrini was inevitably pulled into the histiography of the New Left. While his voice persisted through Italy’s Hot Autumn of 1969 and the subsequent stratification of worker’s under reactionary government, he is not primarily a poet of disillusionment. It’s important to remember that in 1968, change was inevitable. In Italy this change came and persisted for a decade without ever reaching the promise of a coherent socialism. Balestrini writes about the frustration of this promise deferred, but he also captures laughter and kindness, suggesting that greater freedom emerges when people work in concert against global violence. So while his trajectory mirrors many other luminaries of the New Left, like Godard for example, he captures a moment defined by many competing ideas.

The story of Blackout plays out in the sounds of many voices. The simplest aspect of its criticism coalesces against authoritarianism. It catches the violence of repressive government, alongside it’s incoherence: “41. I close my eyes and start to sing/ threads are entangled and transformed into spots whose fance moves/ ever more slowly/ I sang my repertoire then I started the monologues/ with my eyes closed I walked back and forth in the cell four steps/ forward four steps back/ I invented dialogues for two characters that spoke different languages/ like at the cinema when the film ends/ there are those who make love who smoke there are those who/ merely exist.”

But it also demonstrates the multiple voices within a single movement or party. Balestrini pulls quotes from agitators discussing their tactics and goals. He draws on texts pulled from the mass media: newspaper clippings, radio reports, and advertisements. He cuts all of these up and reframes them in an ongoing pastiche. This conversation reflects some of the productive exchange happening every day in contemporary societies straining against bonds. His practice becomes a mode of expanding social vocabularies. There is the mundane and banal language of governance, as the romance of protest is outlasted by another romance. Tension is never reconciled. There is no one way of making the good society.

Through the ambiguity of this pastiche, he elicits and subverts moments of clarity: “48. It’s finally over I’m almost healed of the red spots they are all black now/ seated at the large table on the porch with a gas lamp in front I begin to/ write to you/ completely in the dark and a prey to chaos with the car traffic outside and/ no limit to the amount of congestion/ we were admiring the view when New York suddenly disappeared say/ some tourists/ spilling out of the subway from baseball stadiums and movie houses/ in the confusion some weep but there is no panic/ only the torch of the Statue of Liberty stays lit thanks to a separate power supply.”

In a representative exchange, a student from Brooklyn identifies the case that he recently had no saxophones, after being forced to pawn his. During the blackout, he emerges from a music store with two. He triumphantly grips the saxophones. It’s a classic paradox: “18. A young man with two saxophones stopped me and said five years ago/ in Brooklyn I had to pawn my sax now I’ll start playing again”

Balestrini captures the solipsism and euphoria of experience alongside the frustration of a movement grounded in multiplicity. Much of the collection is steeped in the language of direct democracy. For Balestrini, social organizations are mutable. He identifies the challenges and joys of working with the levers of collectivism; realizing that the possibility of people having sovereignty over the organizations that influence their day to day lives is transitory. And that our social ties trend too often towards consolidation. The narrowing of language that he challenged persists today, with many of the trends he resisted having only become more pronounced. So the collection is timely without feeling too romantic. It’s part of an ongoing project.