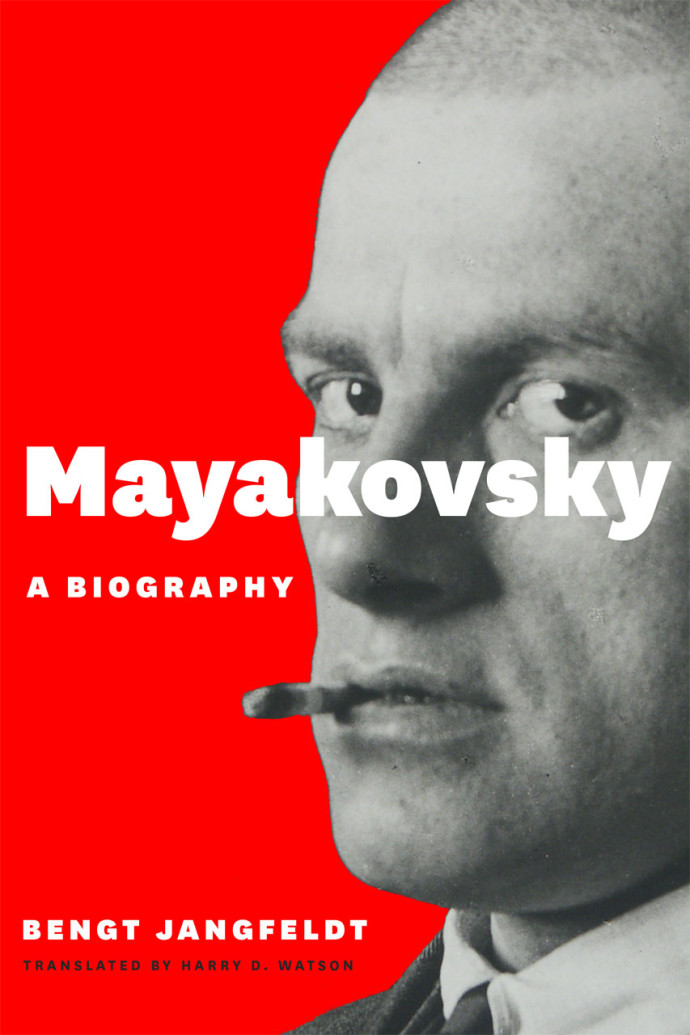

Mayakovsky: A Biography: An Excerpt

03.08.15

The following is an excerpt from the opening pages of Bengt Jangfeldt’s Mayakovsky: A Biography, the most exhaustive study of Vladimir Mayakovsky to date, translated from the Swedish by Harry D. Watson.

VOLODYA: 1893–1915

Through us time’s horn rings out in wordplay. The past is stifling. The Academy and Pushkin are more baffling than hieroglyphics. Chuck Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, etc., overboard from the ship of the Present. We alone are the face of our time. —A Slap in the Face of Public Taste

Vladimir Mayakovsky was Russian but spent his childhood in the Caucasian province of Georgia, which had been under Russian sovereignty since the end of the eighteenth century. The population consisted mainly of Georgians but also of peoples from neighboring provinces and countries: Armenians, Turks, Russians. In the east Georgia borders on Azerbaijan, and the Black Sea forms the border to the west.

He was born on 19 July 1893 in the village of Bagdady in western Georgia, not far from the provincial capital of Kutaisi.* His father, Vladimir Konstantinovich, was a master forester and, according to family legend, was descended from the legendary Zaporozhian Cossacks. According to the same source, the name Mayakovsky stemmed from the fact that most members of the family on his father’s side were tall and powerfully built—mayak means “lighthouse” in Russian. His mother, Alexandra Alexeyevna, came from Ukraine. Vladimir—or Volodya, as he was called—had two sisters, Lyudmila, who was nine years older than himself, and Olga, who was three years older. (A brother, Konstantin, had died of scarlet fever at the age of three.) The family came from the minor aristocracy but were wholly dependent for their living on the father’s salary, which provided a reasonable living without any luxuries.

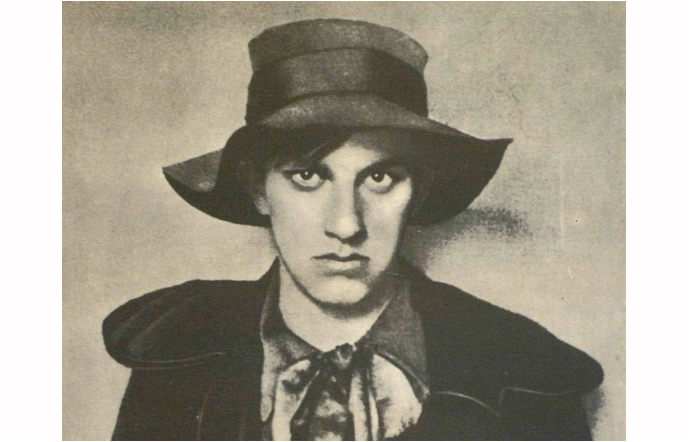

Mayakovsky in 1910 at the age of seventeen.

Vladimir Konstantinovich—a big man with broad shoulders, like his forebears—was a cheerful, friendly, sociable, and hospitable person with black hair and a black beard. He was full of energy and found it easy to talk to people. He spoke with a deep bass voice; according to his daughter, his speech was “full of proverbs, wordplay, and witticisms,” and he knew “innumerable events and anecdotes that he would relate in Russian, Georgian, Armenian, and Tatar, in all of which he was fluent.” At the same time he was extremely sensitive and impressionable, with a fiery temperament and a tendency to mood swings that were “frequent and violent.”

Mayakovsky’s mother was the opposite of her husband in every way: reserved, thin, fragile, but strong-willed. “With her character and her inborn tact Mother neutralized Father’s impetuosity, hot temper, and mood swings,” according to Lyudmila: “Never once in our life did we hear her as much as raise her voice.” She had chestnut-colored hair and a high forehead, and a rather thrusting jaw. Volodya resembled his mother in looks, but in build and disposition he was like Vladimir Konstantinovich, who passed on to his son his temperamental nature and his sensitivity. From his father Volodya also inherited his dark bass voice.

The little mountain village where Volodya spent his first years consisted of around two hundred small farms and had fewer than a thousand inhabitants. It lay in a deep, longish valley surrounded by high, steep mountains covered in forests which were full of bears, roe deer, wild boar, foxes, hares, squirrels, and all sorts of birds. Volodya learned to love animals at an early age. The houses were surrounded by large vineyards and a wealth of fruit trees: apple, pear, apricot, pomegranate, and fig. In direct contrast to the abundance of the natural world were the deficiencies in the administrative resources of the village, which had a post office but neither a school nor a doctor. It was twenty-seven kilometers to the nearest town, Kutaisi, and the only public transport was by coach. When Olga and Konstantin fell ill with scarlet fever, it took so long for the doctor to reach Bagdady that the boy was dead by the time he got there.

The family house stood a little out of the way on the edge of the village, on the right bank of the Khanis-Tschalis River. According to Volodya’s siblings, it resembled “a gold miner’s house somewhere in California or the Klondyke.” There were three rooms, one of which was the master forester’s office. Directly underneath was the surging water of a pebbly mountain stream. The children spent a lot of time outside, and Volodya soon taught himself to swim and ride. He was particularly fond of dangerous games and pastimes, the more dangerous the better. Along with his sister Olga he loved to climb trees and cliff faces and rush around on the narrow mountain paths that coiled around the sheer drops.

The imagination and inventiveness that Volodya showed in his games prefigured the rich creativity that he would later demonstrate. The same applies to another trait that manifested itself very early, when he was only five years old: his ability to recite poetry. His father lacked a higher education but loved literature and often read aloud to his family such classics as Pushkin, Lermontov, and Nekrasov. Although Bagdady was a long way from the public highways, relatives often came to visit, especially in the summer, and on these occasions Vladimir Konstantinovich used to ask Volodya to read aloud for their guests. The boy was not yet able to either read or write but his phenomenal memory made it easy for him to learn things by heart. He recited both well and expressively. To exercise his voice he used to creep inside the large wine amphora which lay on its side on the ground and recite poems to Olga, who stood outside playing the part of the public.

In his learning of poems, just as in his games, there was a strong element of competition. Volodya wanted to be the best at any price and liked to participate in the games of the grown-ups. One game was a sort of “ship comes laden with lines of poetry”: the first player begins to read a poem, stops in the middle and throws a handkerchief to the next person, who has to try to finish the poem. Or they had to find as many words as possible beginning with a particular letter. Volodya’s competitiveness was matched by an unbridled energy which made him never want to stop playing. “Volodya was often obstinate and had the ability to persuade the adults to yield to his wish to continue the game,” his mother recalled. “At such times he would also usually take it upon himself to organize the whole game and carry with him those who were already tired and who didn’t want to play any more.” He brought the same passion and impatience to all kinds of games: cards, dominoes, croquet, and more besides. In October 1904 Olga reported to her sister Lyudmila that Volodya had “become terribly obsessed with playing dominoes” and that he had already managed to win a whole album full of foreign stamps. Here we see the contours of a dominant trait of Mayakovsky’s character, his love of gambling, which we will have reason to return to more than once.

As Bagdady lacked educational facilities, Mayakovsky’s eldest sister, Lyudmila, had been sent at an early age to a boarding school in Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi, and in 1900 her mother and Volodya moved to Kutaisi so that he could start his schooling there. He was seven years old by then. After two years’ preparatory study he was accepted into what the Russian school system called a “gymnasium.” His studies went well, and he distinguished himself particularly in drawing. Lyudmila took lessons from a Kutaisi artist who found Volodya so promising that he taught him for nothing. “Before long Volodya was almost competing with me at drawing,” Lyudmila remembered, and “we began to get used to the idea that he would be an artist.”

Just as striking as Volodya’s talent for drawing and reciting poetry was his total lack of musicality. He could not hold a note and was utterly uninterested in music, he was never seen to go near the piano and never wanted to dance. “When the young people gathered at our house and the dancing started, Volodya was asked to join in too,” his mother recalled: “He always said no thanks and instead went to his friends in the yard next door to play gorodki,” a kind of skittles.

Mayakovsky’s famous image, Как делать стихи (“How to Make Poems”).

TO MOSCOW!

In the winter of 1906, when Volodya was twelve, his father died of blood poisoning at the age of forty-nine. He had pricked himself with a needle while sewing documents together. Volodya was the youngest of his children, but he was very mature for his age and took an active part in the preparations for the funeral. “He took care of everything and never lost his composure,” Lyudmila recalled.

The death of their father was devastating for the family, not least for the son, who from this time onward, according to Lyudmila, “became more serious” and “regarded himself as grown-up.” The way in which his father had died left a deep impression on the sensitive boy’s psyche. He was afflicted with an intense fear of infection which in later life developed into a phobia about cleanliness. He always had his own soap and his own rubber drinking cup with him, and on his travels he always carried a folding rubber bathtub. He avoided public transport, disliked shaking hands with people, and never grasped a door handle with his bare hand, preferring to use his jacket pocket or a handkerchief. He always lifted a tankard of beer with his left hand so as to be able to drink from the side that no one else’s lips had touched—a trick made easier by the fact that he was ambidextrous.

Their father’s death also had an immediate effect on the family’s financial situation. For the past two years Lyudmila had been studying at the Stroganov school of applied arts in Moscow, and in order to provide for her Alexandra Alexeyevna and the children who were still living at home also moved there. In Moscow, Alexandra got by on her widow’s pension and by letting out rooms to students. Volodya and Olga earned their keep by painting boxes, Easter eggs, and other objects. Volodya also drew advertising placards for a firm of chemists.

Mayakovsky had already read a fair amount of radical literature while studying at the gymnasium in Kutaisi, but it was thanks to the family’s lodgers that he first came into contact with convinced socialists. When he was in his fourth year at the gymnasium he joined a social-democratic study circle, and a year or so later he became a member of the party’s Bolshevik wing. At the same time he was expelled from the gymnasium because of unpaid termly fees.

During the following two years, 1908–9, Mayakovsky devoted more or less the whole of his time to political activity. He read and disseminated illegal literature among bakers, shoemakers, and typographers. The police carried out surveillance on him, and although he was only fifteen or sixteen, he was arrested several times. During one raid he ate a bound notebook containing addresses to prevent it from falling into the hands of the police. His first two periods of detention were short lived, one month in each case, but on the third occasion he spent six months in jail, five of them in solitary confinement.

His time in Butyrki prison brought about a change in Mayakovsky’s life. If he had previously read mostly political literature, his reading now took a different turn. “An incredibly important time for me,” he wrote later: “After three years of theory and practice I now immersed myself in literature.” He read the classics—Byron, Shakespeare, Tolstoy—but without great enthusiasm. As for the Symbolist poets Andrey Bely and Konstantin Balmont, he appreciated their modern form of writing but was put off by their themes and metaphorical language. The reality he sensed should be depicted in another way! He tried, but it didn’t work. When he was freed in January 1910 the guards confiscated a notebook full of poems, something he later declared that he was grateful for.

Between arrests Mayakovsky had studied at Stroganov’s school of applied arts, just like his sister. But he had been banned from the school because of his political activities. Nor had he graduated from the gymnasium. He now felt that he wanted to get an education, something that he saw as incompatible with continued work for the party. “I was faced with the prospect of devoting my whole life to writing leaflets propounding ideas taken from books that were politically correct but which were not the result of my own thinking. If you were to shake out of me all I had read, what would be left? The Marxist dialectic. But had not this weapon ended up in hands that were too immature for it? It is a weapon that is easy to use if one only has like-minded people to deal with. But if one encounters opponents?” The quotation is from 1922, but the problem Mayakovsky hints at is no rationalization. The conflict between art and politics troubled him right from the start; it was to color all his actions and hasten his death.

Mayakovsky gave up his political activity, but as he had doubts about his literary talent, his liberation from politics was followed by a resumption of his painting. After four months at Zhukovsky’s art college, which he felt was too traditional, he began studying in the studio of another artist, Pyotr Kelin, where he prepared for his application to the College of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture— the only college which did not demand any political “certificate of reliability.” After his second attempt, he was accepted in August 1911 for the college’s model class.

Mayakovsky (third from right) with friends including Lili Brik, Sergei Eisenstein (third from left)

and Boris Pasternak (second from left).

THE MARVELOUS BURLYUK

Mayakovsky was eighteen when he started at the college and he soon became known for his self-confidence and cheek. He was vociferous, quick-witted, and capable of devastating rejoinders, and as nervy and impatient in his speech as in his movements. He could never sit still on a chair but rushed around the whole time with a cigarette in the corner of his mouth. The dominant impression he made was strengthened by his height—he was about six foot three. His pushiness meant that many people found him quite unbearable—he was liked only by those who suspected or understood “his enormous personality, which exceeded all bounds.” The challenging image he presented was underlined by a consistently Bohemian style of dress: long, unkempt hair, a broad-brimmed black hat pulled down over his eyebrows, a black shirt and black cravat—a Byronic hero in search of his artistic identity.

But his cheek and provocativeness reflected only one side of Mayakovsky’s character. Basically, as a friend from the painting school explained, he was an extremely sensitive person—something he tried hard to hide under a mask of arrogance and an uncouth exterior. Anyone who knew Mayakovsky closely could testify that his aggressiveness was a defense mechanism. Boris Pasternak, for example, gave a telling definition of Mayakovsky’s “brashness” as the result of a “farouche timidity” and his “pretence of willpower” as the consequence of a “lack of will, phenomenally suspicious and prone to a quite gratuitous gloom.”

But Mayakovsky never gave any outward sign of this side of his personality, so when he came across David Burlyuk at the painting school—a fellow artist who was slightly older than Mayakovsky but equally sure of himself—the potential for conflict was there. Burlyuk, a Cubist, was also hit by Mayakovsky’s poisoned arrows. “An unkempt, unwashed giant with the definite air of a hooligan about him constantly persecuted me, as a ‘Cubist,’ with his jokes and witticisms,” Burlyuk recalled. “It went so far that I came close to resorting to fisticuffs, especially as I was interested in sport at that time and in Müller’s [gymnastic] system and so I could look after myself in any confrontation with this enormous, long-legged youth with his dusty velvet blouse and his glowing, mocking dark eyes.” However, it all ended happily, and Burlyuk and Mayakovsky became the best of friends in the “life-and-death battle between the old and the new in art and life which was then raging around us,” as Burlyuk put it.

*Dates in the book are given consistently in terms of the Gregorian calendar, which was in use in the western world. In the nineteenth century the difference between the Gregorian calendar and the Julian, which was used in Russia until 1918, was twelve days, and in the twentieth century, thirteen days. According to the so-called old style, Mayakovsky was born on 7 July.

Excerpt appears with permission of the University of Chicago Press.