Low Orbit: “Packing for Mars” by Mary Roach

04.08.10

Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void

Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void

Mary Roach

W. W. Norton & Company

334 pages

August 2, 2010

–––––––

I was excited for Packing for Mars, Mary Roach’s foray into the logistics of human space travel. I mean, really, “Packing for Mars”? Sign me up. I have a suitcase ready, just tell me what to bring and where to catch a flight.

I’m a Mars nerd, or at least that’s one of the kinds of nerd that I am. The idea of traveling to and maybe eventually colonizing Earth’s nearest, and most similar, planetary neighbor is one that has captivated me since my childhood introduction to the works of Robert Heinlein and Ray Bradbury.

My souvenir “University of Mars” T-shirt, purchased from New York’s Hayden Planetarium, has long since ceased to fit. I have had full-color NASA photo landscapes of boulder-strewn red sand vistas tacked to my wall. Other than the the pink-hued sky and unnaturally close horizon, which make the image unmistakably and intriguingly alien, they look not unlike parts of the Utah desert that I think of as my own.

When it comes to Mars and the prospect of travel thereto, I’ve done some reading. One of the best is The Case for Mars, by Robert Zubrin, founder of the Mars Society, an international organization dedicated to the proposition of sending humans to Mars. It is one of those books I frequently loan and repurchase with evangelical zeal. It talks heavy-lift boosters and escape velocities and resupply logistics in an accessible yet hefty way that makes a layperson like me feel satisfied in having a little more science behind my science fiction reading. He talks tech — engineering, which is obviously important to the notion of space travel.

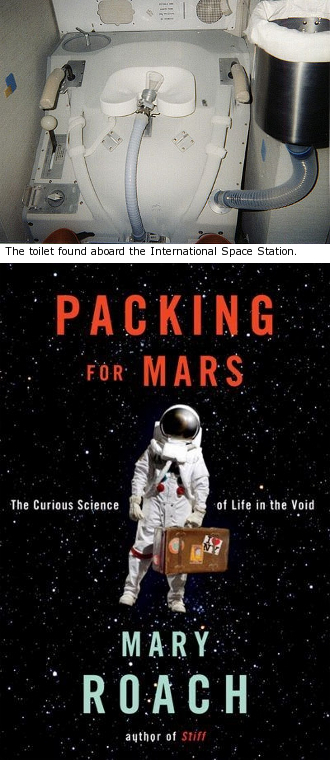

Roach has Zubrin in her bibliography, too, but she’s more interested in the human side of the problem. Packing for Mars opens with the line, “To the rocket scientist, you are a problem.” She goes on to catalogue the engineering problems posed by the human machine and its delicate maintenance. You know, all the extra fuel required to boost the food and various devices required to keep a soft human body alive inside a metal tube in the vast black nothing of outer space.

She drinks booze with old cosmonauts while they lament the lack of vodka on the now-defunct Soviet space station, Mir. She touches on the hypothetical notion of losing an astronaut during a spacewalk and leaving the body to drift in a wholly dignified “burial at sea”. She discusses vomit and poop slightly more than your average ten-year-old boy.

This approach is the book’s strength and its weakness. The idea of Mars is necessarily approached from oblique angles. As there is currently no official plan for a crewed mission to the Red Planet, by NASA or any other space agency, Roach ends up filling most of the book with relevant, yet frustratingly past-tense research into prolonged space travel in general, to, you know, somewhere. Or not really to anywhere at all, but simply the perpetual falling around the Earth by space shuttles and stations that has occupied humanity’s envoys to the void for nearly 40 years now.

So she focuses on the Apollo program and Gemini, which preceded it, to explore the initial confrontations between human physiology and the extremes of space travel. She tags along on simulated missions perpetuated in extreme Earthly environments designed to test the psychological limitations of individuals in groups forced to live and work with the same limited cohort for months at a time. She rides the “vomit comet”, NASA’s training aircraft that flies in a series of steep dives to briefly create the sensation of free fall and hence the zero-gravity of space. She throws up.

So she focuses on the Apollo program and Gemini, which preceded it, to explore the initial confrontations between human physiology and the extremes of space travel. She tags along on simulated missions perpetuated in extreme Earthly environments designed to test the psychological limitations of individuals in groups forced to live and work with the same limited cohort for months at a time. She rides the “vomit comet”, NASA’s training aircraft that flies in a series of steep dives to briefly create the sensation of free fall and hence the zero-gravity of space. She throws up.

She manages all of this with a light, conversational style and sincere enthusiasm. She convinces you that the mundane, day-to-day concerns of pooping without gravity and not killing the crewmate with whom you share a space the size of a small bathroom for weeks on end are equally important as fuel consumption and heat shielding to the success of a prolonged space mission.

Also, she brings you the history of human space travel straight from the mouths of those who strapped themselves on top of barely harnessed explosions to escape gravity’s grasp, and it is enthralling. Again, Roach doesn’t show us heroes stepping down from statue pedestals humming “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” but slightly-shorter than average men (to fit in the capsules) talking about the accumulation of body odor on a trip to the Moon.

There is, however, frustratingly little talk of Mars itself. Roach seems to have page space to dedicate to an anecdote about nearly puking on Tom Cruise in his airplane, but the main topic at hand seems to get lost in the minutiae of eating, throwing up, and excreting in space.

The trouble for the reader lies in parsing where this is a failing of the author and where this is the failing of the governments of the world. She is reduced to interviewing aging heroes because they are the only heroes we have. The will, and with it the funding, for great feats of technology and daring have long since disappeared as national priorities.

The popular and pragmatic argument, as embodied in President Obama’s recent slash-happy NASA budget, is that space dollars are better spent elsewhere. After pointing out that the estimated dollar cost of a trip to Mars is roughly the same as that of the invasion and occupation of Iraq for most of a decade, Roach addresses the practical money question at the conclusion of Packing for Mars: “Since when has money saved by government redlining been spent on education and cancer research? It has always been squandered. Let’s squander some on Mars.”

This is a spectacular and strangely brave sentiment. It’s true that we can send robots to do our scientific bidding at a fraction of the cost of sending people. The risk is less. The cost is less. But, who gets really excited about it? How many people know who Neil Armstrong is? Who knows the designation of NASA’s most recent automated outing to Mars? The perfectly unreasonable intangible appeal of sending people out there is simply in the doing. There is adventure and romance mixed up in all that eating and pooping by actual people doing crazy things that no person has ever done before. And it’s OK if those are the main reasons. I’m comfortable with the sheer frivolity of it. Like I said, sign me up.

________________________________

Mary Roach’s official site.

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Rob Tennant on Indie Rock Writing and Banksy’s Salt Lake Graffitti

Hard Core UFOs: Mike Louie on NASA’s Dark Days and Sputnik