Love Story: Frida & Diego & I

14.02.13

The gentleman on the panel says, “This is a love story.” That is the most important thing about the joint exhibit of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s work: “Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics, and Painting.” The gentleman is an artist from Mexico City and wears a porkpie hat. There are two artists on the panel, Hector Esrawe and Ignacio Cadena, and there are two rooms of color they have designed. There are many mansions in Frida’s house. One is red and one is yellow, reflecting the interior world of Frida and the folklore of Mexico. The foyer of the museum is white and cool and full of people who suspect you of not speaking Spanish. You suspect them right back, the preponderance of black trousers, shawls worn “artfully.” Some days it seems no one you love will speak to you, and then you are left alone in the world-room with visitors of terrible proxemics and no eye contact. Some days you are the only red aspect in the entire museum. And some days you find a double.

I used to think I was the strangest person in the world but then I thought there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do. I would imagine her, and imagine that she must be out there thinking of me too. Well, I hope that if you are out there and read this and know that, yes, it’s true I’m here, and I’m just as strange as you.––Frida Kahlo

I used to think I was the strangest person in the world but then I thought there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do. I would imagine her, and imagine that she must be out there thinking of me too. Well, I hope that if you are out there and read this and know that, yes, it’s true I’m here, and I’m just as strange as you.––Frida Kahlo

I saw her in San Francisco on September 28, 2008, the very last day of her exhibit at SFMOMA. I’d loitered months without going, in spite of a schedule that left a great deal of time for naps and bleak gazes and wandering the City dressed as a bag lady. I didn’t feel like waiting in line to buy a ticket that morning so I’d gone to Berkeley to find an apartment, failed, and returned to find the exhibit sold out. A gentleman approached me and offered to sell me his girlfriend’s ticket because she unexpectedly had to work and he’d seen me that morning. A familiar face in the crowd. I have never felt so grateful for being recognized.

The galleries were cheek to chum, schools of gawkers, and if I hadn’t been so thrilled I would’ve choked.

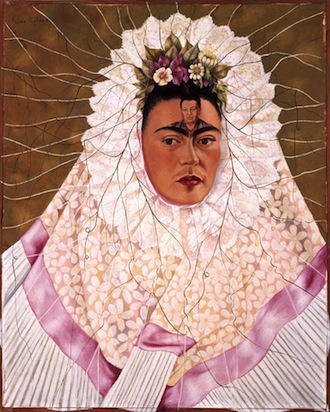

But the experience of seeing her paintings up close, because they are close things, diminutive only in size, requiring that the seer walks near and lingers––a terrible method of art-seeing in crowds––is the same feeling of recognition. Her origin story, her artistic myth, is built on the destruction of her body and the way in which she remakes it throughout her lifetime. Repaints, over and over, reimagines. In the same way, my sister folds laundry and tells me about Joseph Beuys. His personal myth is about felt and fat and the Crimea, the way in which he was reborn, and far more compelling than the original sentence I was trying to put together in the bath about the power of reconstructing oneself in one’s own image as a function of art. It is a particular concern.

I could tell you the story of Frida and Diego, of their two marriages, use the word “fraught” several times, provide context for their Communism, discuss the influences on their artistic practices. But so can any good biographer, and I am not their biographer.

I recommend her to you, not as a husband but as an enthusiastic admirer of her work.––Diego Rivera

I recommend her to you, not as a husband but as an enthusiastic admirer of her work.––Diego Rivera

Months later, the same number of months that would render specificity meaningless, I looked at my socks deciding to leave my boyfriend. We were living in an apartment in Berkeley and I was wearing Frida Kahlo socks that were also from Berkeley. It is perhaps the only place outside of my imagined Mexico that such socks are available, in predictably bourgeoise shoe stores. It was the season of the gladiator sandal and I was determined to find a similar yet attractive sandal I could walk in. Those were the walking around days. When I moved to Atlanta some time later I discovered myself in shoe stores that sold heels exclusively and surrounded by shit sidewalks. No one walks, there is only stepping in and out of air-conditioned cars. The Berkeley boyfriend decided that he didn’t care about being an artist. Perhaps there are some who are content with being artistic in their off hours. Perhaps he got enough art from his parents being artists. Perhaps it is indefensible to say “I cannot love you if you will not make art.”

* *

I love someone who is an artist.

It is 46* and blustery, the sky looks like it was painted on for Halloween with bare trees set blackly against it, thick furls of grey cloud with stripes of pale between them that would suggest snow if it were colder. We eat Mexican food and imagine being aztecas rather than estadounidenses. There is some spiritual aspect that has been lost from our daily lives, or that the original Puritans rigorously bred out, or that consumer culture has tried to smother. After lunch we go across the street to the Oakland Cemetery. Some landscape artists are taking a break and drinking something hot by their truck; we are mainly alone. There are daffodils, but they seem anemic to me, awfully spindly, and I wonder if perhaps I haven’t been spoiled by more robust flowers from warmer climates. Probably. It’s too cold to house-hunt mausoleums so we loop around and say “hi” to Margaret Mitchell, who is at home to visitors around the back of the Mitchell family monument under the name Marsh. She knew that great romance is not simple.

I do not know how she felt about flowers, or art, or ceremonial Aztec garb.

You will be called AUXOCHROMOS, he who attracts color. I am CHROMOPHOROS, she who gives color. You are all the combinations of numbers. You are life. — Frida Kahlo

You will be called AUXOCHROMOS, he who attracts color. I am CHROMOPHOROS, she who gives color. You are all the combinations of numbers. You are life. — Frida Kahlo

This is a love story about two artists and I will let you pick which two. There are the faces in the crowd that you recognize and the faces that respond with recognition. There are the eyes that will look you in the eyes, and mirrors that reflect your gaze.

There is no handholding in the galleries. There is a double bed, in the way that a bed that has been multiplied by two may be called “double,” looks into itself, and that its intentions lie. There is no repose. There are photographs of each artist and also together, where she fits into the corner of his arm, with an equal and different gaze. They intersect in their portraits of each other, and photographs in which they watch each other paint. This is a story about larger and smaller bodies––not which has the greater gravitational pull, but that in combination have an impact much larger and more nuanced than separate. A complete range, through the colors and forms and schools, the particular and the general, the political and the personal, the postcard and the mural, the triumph of survival and the triumph of industry, the story of a life and the story of a country. Their legends combining into a product rather than a sum.

The components of their joint myth are laid out line by line, but let me tell you that the object includes the glance, the glass eye watches on its chain: here is the eye of a painting, here is a painting of the color that eye beholds.

__________

“Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics, and Painting” is on exhibit at the High Museum of Art through May 12, which is the only U.S. stop on its tour.