LITTLE WAR

08.08.14

‘Between you and me, I will not give up,

will never leave the mausoleum of my feelings

to the vultures’

—Christina Chalmers

for Antoine Berard

This name, Batignolles, comes from either ‘bastidiole,’ meaning a little country house, or from ‘batagliona,’ from the Latin, for “little war.” The land belonged to the Benedictine women of Montmartre, and later was hunting ground for nobles, replaced after the revolution with farms, farmers. The light here is bare and crepuscular; it’s a sequence of nuance. I’m sitting again at the writing table, trying to develop a conceit around the neighborhood I’m in, the Batignolles—dealing with, on the one hand, the very interesting history of the rail fallows along the rue de Rome, and on the other, desire itself, instantiated at times, in my desire for the poissonnier who I bought some fish from this afternoon.

I’d like to submit to the levity of it, that is, feeling the irony I’m poised to endure in this city, the elaboration of lust being all around me, sa lubricité. Really, I’m the spitting image of it, walking through these streets in dark red lipstick. O cosmopolitanism. O defenestration, the water or the washing coming over. O chaleur! I was trying to write to Luke, but loosing my train of thought, as the barista turns up the music.

I often struggle to be polite, aux folies—I’ve feigned and guarded, as for me, we were known to have fished and eaten fish out of need. My father was a wrestler and me, a poor mason’s daughter. I was worried that it all had to come from inside of me. That the concept couldn’t be developed on the surface. The love of surface lost on what was once hunting ground and replaced with indirect domination, with glossolalia, or new worldedness, subject to a more diffuse practice of power, and a changing belief in nature.

*

At first use a butter knife. Scale the tail, and move toward the head. Scale near the fins and under the collar. Start gutting by slipping into the vent and slicing upwards, away from the intestine. Force the knife through the bone between the pelvic fin and the base of the lower jaw. Remove the guts by grabbing at the base of the head. Scrape out the liver, the swim bladder, a whitish sac. Cut the gills at either end of the arc they form. Or rip them. Wash in ice water.

I remember opening an animal for the first time, and thinking of course, that it is brutal, but so was my species with itself, thinking one uses so little, only the meat around the bone, and thinking it would be like this if something were to carve up my little body, even graciously; this is what we call the essential self, the being oneself a remnant, that which is left over, after being picked apart by anything with its own gravity, you start cutting at the parts that could be integrated by others, discarding what could belong to them, or shared between you, forcing the knife until you can only see the degree of waste a thing is.

*

Antoine says that if you’re ever looking for a place to fuck in the city of Paris, just push open the first door—the right one, he says, will always open. This reveals something about his obsession with fate. What was Simon saying the other night, was it really about fate? Something too about vengeance—oh, yes, that it can’t be justice, or can’t be justified anyway. I am thinking this in The Cri-Cri, as the old men take their vin blanc and cigarellos. I have this horseshoe shaped burn from when Antoine let the lantern get too hot and the top blew off into our little cold bed in Montreuil.

How do I continue to find you in all these cities, this occident, and what a sickening joke the new world is. We are living inside place names. Have I taken you against your will, into the recesses of feeling, taken your name there, with me, taken your provocations, your minute resentments, your property. Are you afraid to stumble in the basement were I keep my things in their season. Should I have given you more tenderly the already ungovernable parts to keep in your locker under a light?

*

The rail fallows: I was walking down the rue de Rome, on the errand of Birthe Muhlhoff, to deliver the keys of her flat to her proprietaire before the first of June. I had just met Birthe, in the house of Danilo Scholz. Since Danilo and Birthe, and the other very pleasant German academics of their flat are leaving for the south of France, I was charged with the errand of going to 6 rue d’Edimbourg with Birthe’s keys, near the Gare Saint-Lazare.

I’m walking: to my left, this deep train valley, with 19th century apartments and green lawns sidled up to the edge of the embankment. Above, electrified train cables. I was snapping a few pictures when a man stopped me. He said before trains existed, the Batignolles was just a village with farms, famers, cows grazing all over the hills, this hill, the hill of Batignolles, where the Rue de Rome now is. He said when the trains came they built these lines, underneath the hill, and a series of tunnels for the trains to pass through, where there’s now only steel and soot and graffiti. He used words for ‘burning,’ ‘burnt,’ ‘engulfed in flames.’ He was saying something I didn’t catch about wood, something wooden. Because of the fire, and because of there being so much death, the tunnels had to be deconstructed. But now I’m late, being that I’m meeting Simon back at mine in a half hour, so I issue my most convincing thanks to the man for his story and proceed with my errand. I’m on my way to 6 rue d’Edimbourg, to the house of Madame Peltier, who Birthe Mulhoff says voted for the Front National.

*

Little war, little peace, little love, little military exercises. What was once hunting ground for nobles replaced after the revolution with farmers, in indirect domination. I was reminded today that historically speaking, the appropriation of male peoples has always meant a campaign. I am now returning, in my solitude, to all this talk with Jacob about first nature, second nature. Returning to all this talk with Christina about experience and subjugation, about location, and reversal. About the violence of reversal, or the reversal of violence.

As for this order of nature: you act as if it doesn’t exist because there is no way to measure it; it is immeasurable with respect to the epic pre-emptive claims it makes, that one person can own another, that it is easy, that one kind of person could own all the other kind, that it’s immeasurable and therefore exhausting. And mostly we are exhausted and unmoved, even if at times a flare crests the wind and plaining voices rue inside this very long, little war, the opacity of it, around which we stumble as if looking for a light.

Would that I were a boy, and could travel like one, would that I could travel like Evan Kennedy through the Holyland, talking to men in the cafes, would that I could “lament and love and go about the afternoon with an unchallenged captivation in my demeanor.” But I can’t exchange form for blending with the tone of a city like glass. So my body becomes the prize for whomever accelerates dismantling the hesitation I’ve designed, that is, what precipitates, or collects: as tribute.

*

I was walking down the Avenue de Saint-Ouen, which is arguably inside or outside of the Batignolles, depending on one’s orientation to the center, to the administrative or proprioceptive definitions. Because I can feel the lust of elaboration all around me, and because I’m the spitting image what most would call persuasion, walking through these streets in dark red lipstick, cosmopolitan and anarchic, meaning alone. And because at times I feel the blood rushing through me, only slow enough to notice the sweet breaking feeling, of breaking over my own denial of weakness, of being made weak by anything, and holding onto that bad, very bad, sensation—catholically. I thought I would love to meet someone this way, in this dress, under this afternoon sun, but because ‘shame’ is the perennial theme of this melodrama, of the story of foreignness, this is how I would meet the poissonnier, without language, or coherence.

It must have been the blood rushing out of my head, but all alpha-numeric units fled. The inability to speak either language I know—searing. Undoubtedly, my propensity to be attracted to the fishmonger is Oedipal, as I cathexed to the image of his rubber apron, as I failed to even really look into his face. O catastrophe! I’m left with only this receipt from the ‘Petit Chalutier’ for 2 euro 81. I walked home from the Avenue de Saint-Ouen, full of honte muttering ‘quatre-vingt-un.’ The real crisis, for now, endowed with the potential to redirect the trajectory of this opera, deals with whether or not one should go back to the fish market, even when fragile with uncertainty: to stalk or not, the poissonnier.

But what of desire then? What of its red windmill creakily grinding into the light polluted night generating nothing? And what of sliding haphazardly off the love of surface, realizing you were all the while on hunting ground, that there is no façade, no new-worlding, no ‘indirect’ form of domination, or master language on which to build up the gleaming facets of the spirit, ever subject to the tartuferie of power, and to the dissolution of what you could mean each time you say nature. As Antoine says, you have your fragility, and they have theirs.

*

He said the valley of tracks was once a spring with animals grazing. When trains were made they dug out the spring, so the cows grazed the top of the hill in the Batignolles, until there was a fire below.

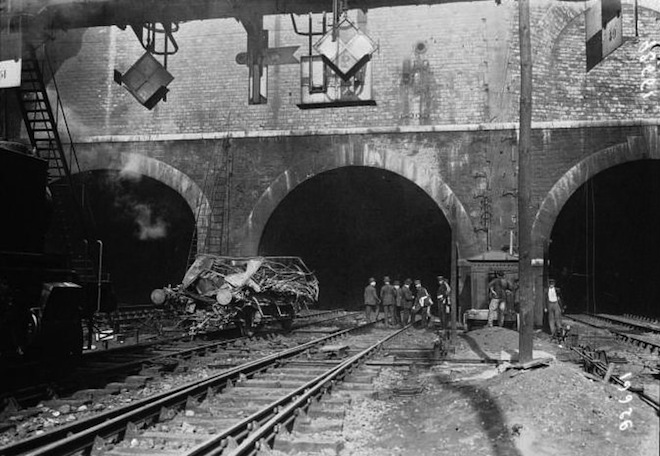

The rail lines unfurl down the rue de Rome as they approach the Gare Saint-Lazare. In the west, a trench was dug, and four arches built, named: Saint-Germain de Laye, Saint-Germain Argenteuil, Versailles, and Auteuil, the last in 1909. In October 1910 there was a strike of cheminots, and the army was brought in to prevent workers from destroying the locomotives. October 1921, a commuter train stops abruptly, from a broken connection. A second train hits the first. The tunnel, being filled with smoke blocked the view. Because the train cars are wooden, and because the tunnels are cylindrical, lit by gas fire, the trains are kindling in a furnace. It burned for days. Remains of a crushed car in the gallery. And all the tunnels were deconstructed, even Auteuil, under the rue de Rome.

They crush a tunnel from the top and only then scrape the contents, stripping the field. The steel hangers are left, then gradually removed. The trench of the future ahead.

*

Speaking with derision and generality about the grumbling affective disposition of the French peoples loudly on a bus in Paris in the weeks immediately following the election of the Front National, could, in some cases, be described as sport, based on the necessity of strategic thinking, the apparently immanent contingency of volition, and of course, the risk of bodily harm. It helps if someone on your equippe is French, even if that person spends so much time in North America his accent is like a puddle brimming or colors running or fly eggs hatching, even if he is often mistaken for Belgian, which is something of an insult, I suppose. Having spent the day ingeniously, that is, casually inebriated, talking about the usual, the important, the dangerous, and the ineffable, at times speed walking through arcades, to assuage the specter of possible tardiness, as we have dinner plans with Rob, Antoine and Luke and I are taking a bus back to the Batignolles. Antoine is positioned in the middle of the bus, on a riser, a perfect place from which to give a speech, and we are a bit closer to the doors, from which people are leaping to the streets at each stop, predictably grumbly when they are unable to leap fast enough, and we are careless, meaning, a little drunk, and only concerned with not getting controlled on the bus as we are making good time back to the Batignolles. Antoine begins an anecdote in English about the boarding of international flights to France, and the predictable grumbling of the French peoples. This elicits the rolling of his bright blue eyes into the back of his head, which in turn elicits the intervention of a man in a tailored gray suit who is genuinely upset at the effrontery of his country, at the ease with which Antoine might say, “Fuck France.” You can imagine how things unfolded from here, and though this man, in his tailored gray suit and prematurely balding white head, did not throw a punch, his body was shaking with adrenaline so completely, it seemed he was prepared for just such a hazard; and being that a fist-fight over the appropriateness of mocking one’s holiday territory would have killed the mood, we decided to let the man fling his insults, and his patriotism, and his racial theory of the loudness of anglo-saxons all over the Avenue de Clichy at the metro La Fourche, until he went grumbling away and the three of us went up to Danilo’s apartment, put on some Motown and did the Watusi. So this is also a story about desire, as it adumbrates the relation between desire and the prospect of force.

*

Smashing trains: this dream of politics, what it does to the blood. Simon and I agreed, after I had sketched the geography of the active minority, had noted the calibration of allegiances, had represented with decorative arrows the teleology of separation across tendencies, we agreed that the bad world, and all the sorted types of exile it supposes were better than the world conceivable as exodus, propagatory in purpose and puritanical, at least perspectivally speaking, since only now can I again see each tin door closing, and men coughing at the bar, while Monica tells me where her mother lives, on that other continent, in a country once fought over, in what by twentieth century standards was, a little war, where one group of men tried to appropriate another, for one hundred and three two years. We agreed, Simon and me, that we could see grace, as substance and as substrate, better from here anyway.

*

It was only after an immoderate amount of research that one finds mention of “the accident of October, 5th 1921 in the Batignolles tunnel,” that there was a fire that burned for days after two trains had collided in the tunnel named ‘Versailles.’ One can find engravings of the construction and deconstruction, only a few decades apart, of the four arches that were once there.

I discovered that the Batignolles was the original site of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the train station immortalized in the eponymous paintings by Claude Monet. When I snapped a photo of the rail fallows, with the red and white tile-work spelling of “PARIS ST. LAZARE,” I didn’t think anything of it. In 1872, Edouard Manet lived at 4 rue de Saint-Petersbourg, equidistant from the former station and the current location of the Gare Saint-Lazare. He painted the rue de Rome in Chemin de Fer. For him, the engine of the train, represented by the smoke against the steel bars of the fallows, was the intelligence of that century, the glory and the fortune.

Luke and I are walking there. I show him the rail fallows, and the sign of the former station. The fallows closest to the metro are sheathed in mesh wire fencing over steel, but I remember that the mesh ends as you approach rue d’Edimbourg. I say to Luke, let’s walk down a bit, so we can see really the tracks.

*

Antoine says if you’re every looking for a place to fuck in the historically communist village of Montreuil, just try the door code “1789.” I was thinking about force, which for us is thinking resistance, and about its counterpoint, surrender, that is for me, a giving in to all the love I feel, and I am wondering whether it even makes sense to place desire here among these nettles. We know at least that love is inseparable from the signatures of this world, of all the little wars, made visible, our love indexed by wars, steeped in predication; vengeance. I was walking down the rue Marceau, and wounded myself—the alacrity with which I picked a pale pink flower—and saw that some one had filled a whole garden wall with the phrase, “La Jeunesse emmerde le Front National.”

Between these things, is you. It is the ‘you,’ and it’s my solitude, and it’s these bizarre theological seances with Simon where we are speaking seriously of grace. It is the ‘you’ in the front and back of each thought, of the Batignolles, and the fish, and the bad choice of wine I made this afternoon, in the chaleur, and the lourd. It’s what’s happened to my heart as I am standing at the bar of the Etoile de Clichy, talking with Monica, with the boys watching football and speaking Arabic in the backroom; my heart as I told Sophie before the gardens, yes, I will always love you for exactly what you are, there is nothing else to do, or to expect. To talk about trains colliding through a dark expanse would be too easy. Where does my heart live when confronted with the autonomy of objects? My heart as if in parallax of the fray of everything just as it escapes.

What we have come to understand so far: that all states are bad states, even after the revolution. That all poems know more than us. That we practice a species of power, if for some, power is something we have been known to fish and eat out of need. That some of us are leguminous. That some look like persuasion, to a fault, and play it like brass. That somehow some believe in fate, when some believe in hunger. That it is not our nature, or theirs, with which we organize or mitigate the surface. Jacob’s french horn playing pouring honey down the stairs into the garden. O my love. Come over. Vouchsafe my silent ears to deadly swannish music.

12 June 2014

————————

Jackqueline Frost is the author of The Antidote (Compline Editions), You Have the Eyes of a Martyr (O’clock Press), and Young Americans, forthcoming from Solar Luxuriance. She lives in Ithaca, New York.