Listening for the Voices We All Hear: A Conversation with Scott McClanahan

23.06.16

Scott McClanahan has no friends. He tells me this via email, but I am skeptical. Our correspondence, much like his prose, walks the line between fact and fiction, sincere and tongue-and-cheek. Some newspaper called the New York Times says McClanahan’s prose is “a rushing river of words that reflects the chaos and humanity of the place from which he hails.” They say a bunch of other really nice stuff about him that happens to all be true. I’m not the biggest fan of the Times, but it’s nice to know they can still get it right every once in a while.

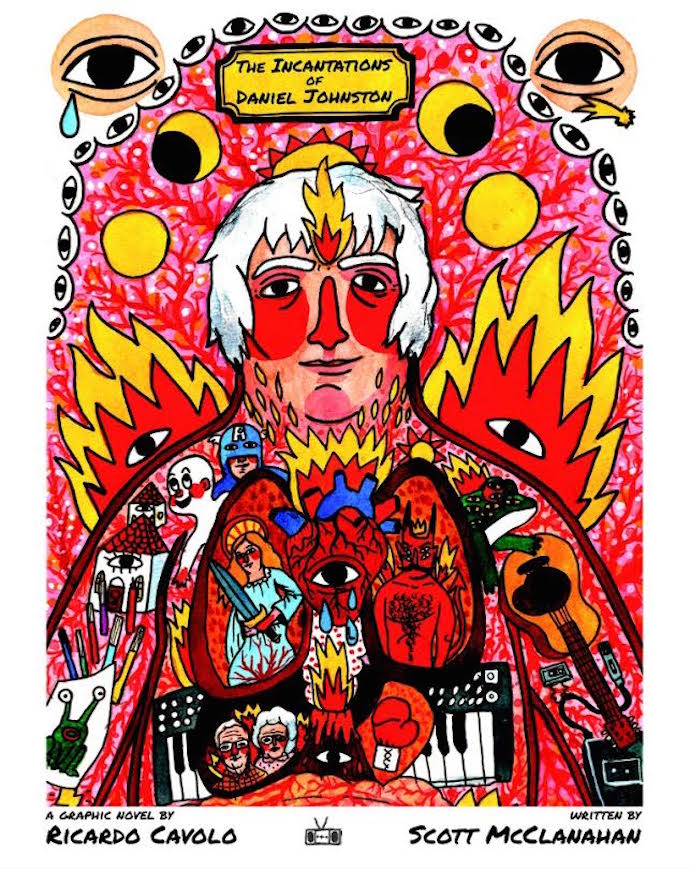

Scott’s latest project was to provide the words for The Incantations of Daniel Johnston, a graphic novel illustrated by Spanish visual artist Ricardo Cavolo from the consistently-stellar indie press, Two Dollar Radio. It is mesmerizing, equal parts ebullient and ecstatic as it is frightening and tragic. Cavolo’s playfully psychedelic illustrations and McClanahan’s dizzyingly-hallucinatory and infectious prose work together to forge a dark alchemy that summons Daniels’ angels and demons, that reaches deep into his mythos both for inspiration and to debunk. McClanahan says the project is cursed. He tells us this much in the book and insists it is so in the conversation we have. But he also says he has no friends, so it’s hard to say. The way I see it either he has no friends and we’re all fucked for reading the book or Scott is very popular and we’re all safe. I’m betting on the latter but I’ve also never been much for betting. Take a chance and preorder the book here.

Could you talk about the inception of this project?

Eric from Two Dollar Radio asked me if I was interested in doing the text for a graphic novel. I guess I didn’t process it at first because I kept thinking he was asking me to write a dirty book or something. For a second I was thinking, “Something graphic. What are you talking about? I don’t write porno.” Then I realized he said “graphic novel” and I thought, “I don’t draw. What a dumb idea. Eric’s on drugs.” This was followed by another 10 or 12 confusing conversations inside my head. I’m still wondering how the thing actually happened.

Have you ever collaborated on a writing project before? What was that like?

I don’t even have any friends let alone collaborators. People who publish books with their friends seem like wizards to me (Mira and Tao, Blake and Sean). Literal Wizards. I just want someone to tell me how you get a friend to begin with and then I’ll worry about writing a book with them later. Collaborations seem like a whole new way or writing though. Like the future almost. I mean that.

I guess in the end I was just really taken by Ricardo Cavolo’s art. I’m sure if Goya were around today he’d be making graphic novels. Cavolo had already published the book in Spain and so I had limitations. The page numbers were set. The images were set. I just used Google translate to get the general gist of what he had written and then I did the exact opposite. I kept imagining Cavolo’s voice inside my head saying, “This heel-belly is ruining my beyootiful comic. I hate him.” For some reason it was always a French voice inside my head cursing me, rather than a Spanish voice.

Who is Daniel Johnston to you? Were you a fan?

Oh man. That’s a big question. I wrote a whole book about it, but I guess I’ll answer with this clip. This explains everything.

Do you believe that everyone who makes something is really just saying, “Hi, How Are you?” and “Beware”?

For sure. Interviews are about making sweeping generalizations right? So I’ll say art can be broken down into two categories more or less: companionship or warnings of demon possession. These things we make are just seductions (even if the artist is no longer alive–like a weird necrophilia of the spirit across time. You are either seduced by it or not). But I was serious about the beware. The curse I put in the book is real, but now I’m super paranoid that it’s only going to be a curse for me.

Whenever I’ve dabbled with any stuff like this in the past the shit has always blown up in my face. I guess I would say if you’re not prepared to have your life ruined–then this probably isn’t the book for you.

But that’s always been the fun of the stuff I’ve loved. To be destroyed by something, to have something take over you. I think it’s my childhood fear of seeing trials about teenagers driven to suicide over the lyrics to Judas Priest songs and little Christian Scott thinking, “I’m not in control of my life.” And of course, I’m not. You’re not either.

I really am drawn to and fascinated with the level of self-awareness this graphic novel contains, both in your text and in Ricardo’s illustrations. Do you see breaking the proverbial fourth wall to be any sort of a risk?

I always get this “fourth wall” thing and to be honest I don’t think I even understand what the other three walls are. It’s like having somebody explain what a “novel” is. I guess if I knew what the other three walls are then I could answer.

I’m sure it has something to do with how rooms are made up of four walls or something. If you break one wall, then you can see into the next room. But writing has been doing this since the King James Bible and Sappho and Catullus and Diderot. It just shows how dorky and conservative most of us writers are.

I don’t think people realize that books are fake and you can do anything you want with a book. Anything. Of course, I guess I could have spent two years working on one of those typical literary third person novels an agent wants you to write where you end with a sentence about someone looking out a window or hearing something in the distance, but I’m not interested in prose as embroidery like most writers. I’m more interested in doing something different like this. This seemed fun and really a dumb thing to do as a “serious” writer of prose. I want that carved on my tombstone: Fun and Dumb.

The scene where you say it doesn’t matter if he did or didn’t join the carnival because he did in this book felt so important to me. This graphic novel manages to somehow both fuel the legacy and mystery of Daniel Johnston and simultaneously deflate that same mythology and romanticism. Was that all intentional?

That’s always the danger, right? It’s the old Kubrick idea that every anti-war film is actually pro war in the long run. It’s the same with Atheists. It seems like the only people who talk about god anymore are atheists. All the fucking time. The rest of us just kind of like, “God? Who?”

I really don’t think I was thinking about these things as I wrote it. I’m sure I was to a certain extent, but I had a practical concern above all. I was just trying to fit words into these little boxes. I talked to this college class last year over Skype and they asked what I was working on and I said, “I’m working on this thing where you have these little boxes and you have to fit a certain number of words in them. And then there are pictures that go along with the words.” People just shook their heads once they figured out I was talking about a comic and laughed like I was stupid, but that’s really the challenge. Getting the words to fit.

I noticed the recurrence of the words hope, wish, and pray. Daniel does a lot of wishing and hoping and praying to become famous, and you tell us that fame is the very thing that destroys him. I wanted to ask you if you think these are also the things that make all of us human. Is it human to in some ways, self-destruct?

Yeah, isn’t that the purpose of life? To destroy yourself (or at least prolong this destruction over the longest time possible). I quit bad things a couple of years ago because of the state of my mental health and eliminated eating beef jerky from my diet for dinner (stuff like that). So I started eating nuts for my snacks. Nuts, nuts and nothing but nuts because they’re healthy right? But now I have a condition called diverticulitis which makes you pee blood out of your butt. So maybe I need to go back to beef jerky.

I think Daniel would have been just as spiritually destroyed by not achieving some sort of fame. It’s real easy to say that he couldn’t handle it or he wasn’t equipped to handle it (even on the minor level he has experienced). But it’s probably even harder and more destructive for an artist to be ignored. You can literally kill an artist with a polite pat on the back. I’m sure all of us would rather deal with being on MTV. There are artists being destroyed right now, as we speak, because they aren’t being destroyed by this other thing: recognition.

Your frenetic prose and Ricardo’s beautiful and hallucinatory illustrations, the repetition of certain morbid phrases (“D in front of eye is die”) and omnipresent duality present in the language all in some ways worked to make me feel a bit manic (conservative observation). I was wondering that disorienting effect was perhaps all intentional to maybe make the reader feel a bit like Daniel?

Sure. The idea of writing for me has always been to have your work found in the possessions of an assassin after their arrest. To have your work found at a crime scene. This is always what you want to do to a reader. I always like the idea of Duchamp putting his geometry textbook outside so the weather could learn about the facts of life. That’s what this form does. The thing I like about comics is that there’s still something we associate with childhood from it, and there’s something so primal about a picture placed together with a word. It’s like our mother or a kindergarten teacher reading to us during nap time. I remember feeling controlled by stories when I was young and there was something dangerous about them. It’s that way with a ton of children’s books. The Little Prince just feels like sadness and violence to me. I remember thinking when I was four years old I was going to be devoured by a monster at the end of Grover’s There’s a Monster At the End of This Book. I was trying to do my own version that here.

I asked about this books role in perpetuating the legacy of Daniel Johnston, but I wanted to ask, in a separate way, was it important to you or this project to demystify mental illness or portray in in a more realistic manner?

Nah, that wasn’t my intention. I guess my last couple of answers about intentions have probably been dishonest as well. It’s probably more like how one time my former father in law got up in the middle of the night and cleaned out our freezer of these little ice cream cups. The next morning he complained that our ice cream was freezer burned and we should throw the rest away, when in reality he had been eating the ice cream we bought for the dogs. Frosty Paws or whatever. So I guess you end up doing stuff all the time you don’t realize you’re doing. It’s better to do it that way than to consciously think, “I want to eat some ice cream made for dogs tonight.”

Towards the end of the graphic novel you say, “And we remain mysteries to ourselves as well. For every story told about someone else is about the person who is telling it. Like Scott McClanahan. Like Ricardo Cavalo.” In what way is this story about you? How much of writing this was personal, and in what ways is it so?

I’m really interested in biography right now as a form. I’ve had about enough of language novels or “literary” novels or “weird” novels or autobiographical novels. Not to say I don’t like them. But biography feels like a whole new place we could go. We still look at it as a scholarly form when it is so subjective and open like the wild west. Robert Caro is selecting the facts for his books on LBJ. I heard a podcast with him the other day and he was describing how he found out an anecdote for one of the books was true and he verified it. The story of finding sources for the anecdote was more interesting than the actual anecdote itself.

Beyond that I guess I’m really excited about the future of the book. We’re going to be able to incorporate text and images and music together in one thing that you can hold in your hands. Technology will allow that. Not to say I don’t still love traditional books, but it’s a new art form. We just need somebody to come up with the app. Better get on that millennials.

At the end you postulate an idea, “What if Daniel was right about Satan and the voices in his head? What if the voices are real? What if he was drawing and singing the truth about being damned?” At first, this notion of pondering if Daniel was right seems so preposterous, but by doing so you are simply allowing him the same control or “sanity” over his life that many people enjoy their entire lives. So in a really strange way, it was kind of a beautiful ending because it empowers Daniel and his songs, his art. Do you agree? Was any of that your intention?

I think modern medicine and psychology have helped millions of people. They have helped me as well–so I’m not saying anything negative here, but I think there is something so condescending about the way we view mental health. We have replaced the metaphors of the past and ancient cultures and ideas with more modern metaphors. It’s like what I say in the text: a young girl can see visions and hear voices in the French countryside and she can become Joan of Arc. That’s not true today. We would see her as ill and in need of treatment. We would treat her primarily with medication and her visions would be proven false.

What I was trying to say at the end is that we all hear voices. All of us. Try to turn off the internal voice inside your head right now and see what happens. This is part of having consciousness. I just wish there was more room for these voices and eccentricities in our lives. If you are harming yourself or you are harming someone else, then of course something needs to be done there for your safety or the safety of others. But I have had manic episodes where I could really see something about my humanity, about my own place in the world, about God. There’s something so condescending about saying that none of this is “real” or whatever. That the Seroquel I take today is not anymore real than the buzz I used to feel in a fit of an episode.

We do this with the past as well. We look back at it as so barbaric and oppressive, and we laugh about their kings and queens and funny beliefs and feudal systems and yet we’ve just replaced the kings and queens with celebrities. We buy celebrity shit in order to provide them with our oath of fealty.

When it comes down to it, it’s like what Sam Pink said a couple of weeks ago in a tweet: Everybody talking about how to improve the world and 99% of people can’t even make a decent paper airplane.