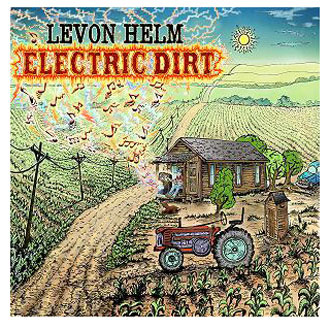

Levon!: Levon Helm, The Dirt’s Gone Electric

16.09.09

Titans stride through The Last Waltz, Martin Scorsese’s elegiac documentary about The Band, the mostly-Canadian supergroup who started out backing Bob Dylan and finished up as unlikely conservators of Southern-American music and culture. But no matter who else is around—Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters—I can never take my eyes off of Levon Helm when he’s onscreen: That lean, scruffy, wolfishly handsome face; a knife-blade of rural cunning in a well-traveled sheath.

Titans stride through The Last Waltz, Martin Scorsese’s elegiac documentary about The Band, the mostly-Canadian supergroup who started out backing Bob Dylan and finished up as unlikely conservators of Southern-American music and culture. But no matter who else is around—Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters—I can never take my eyes off of Levon Helm when he’s onscreen: That lean, scruffy, wolfishly handsome face; a knife-blade of rural cunning in a well-traveled sheath.

All Band fans have their favorite Band singer, but nothing defines the group in public perception so much as Helm’s iconic vocal turn on “The Weight.” His drumming, like his voice, was both powerful and ragged, freighted with the farmer’s weary persistence. Helm’s body language was that of a lifelong hustler: an intractable yet skewed set to his shuffling shoulders, like a man dealing marked cards. In the interviews, he was taciturn, with a mildly-impish version of courtly Southern manners, very calm in affect. Yet there was a riot in his eyes: a mischievous gleam, backlit by a deep wound or haunting that only vanished when he sang, and then only because his eyes were shut tight. Those eyes make me interpret his body language as a drummer differently—as that of a man with an immense weight on his heaving shoulders.

As the only genuine Southerner in a band that mythologized the American South, Helm did have an insupportable folkloric payload to bear. He was part Paul Bunyon, part Atlas. He actually grew up in place called Turkey Scratch, Arkansas; he actually had cotton-farming parents with the unbearably poignant names of Nell and Diamond. Helm could sing “like my father before me/ I will work the land,” and mean it. He was the heart and soul of the Band, disgorged from the very soil they mythologized, carrying it under his fingernails, drenched in its local idioms—blues, country, folk, rock, gospel. There was always something of the loner or outcast about him: His bandmates measured the land against their dreams, but Helm took his own measure against the land, always threatening to buckle under all that history.

Helm’s physical aspect—the wounded hustler—expresses the series of exiles that have informed his life. First, he was torn from the native soil he loved so well, to distant Canada, to play with Ronnie Hawkins’ band, the Hawks. The South, for Helm, was forfeit, but he still had the dream of it he created with his bandmates—and at a time when the South that Helm idealized was faded, its ugliness overwriting its virtues in the collective consciousness, perhaps the dream seemed more sustainable. But the Band gradually broke apart like the dream itself, and he lost that as well. He still had his voice, a column of flame in which Southern traditions were transfigured, and then he lost that too, to throat cancer, around the turn of the millennium—an entirely too-symbolic moment for the avatar of vanishing American idioms to fall silent.

And then, miraculously, his voice returned. It was changed—certainly an older man’s voice, rusty and flaking at the edges, but clear and pure at the core—changed in the manner of a seeker coming back from the wilderness, possessed of new knowledge. It was still Helm’s voice, but charged with greater depths of emotion, as if he’d plunged into his silence and extracted a pungent sense of mortality. He made an amazing return to music with 2007’s Grammy-winning Dirt Farmer, with its double-edged title: Helm was still, in his heart, a farmer, as if his decades of pop stardom were a long hallucination. He was also pushing 70, and grappling with death in a way that was not at all symbolic or metaphorical. If Dirt Farmer was a rebirth, it was one where another death, final and uncompromising, waited close at hand. Between his short silence and the inevitable long one—between the vanished South of his childhood and the vanishing world at large—Helm makes his last rebel stand.

And then, miraculously, his voice returned. It was changed—certainly an older man’s voice, rusty and flaking at the edges, but clear and pure at the core—changed in the manner of a seeker coming back from the wilderness, possessed of new knowledge. It was still Helm’s voice, but charged with greater depths of emotion, as if he’d plunged into his silence and extracted a pungent sense of mortality. He made an amazing return to music with 2007’s Grammy-winning Dirt Farmer, with its double-edged title: Helm was still, in his heart, a farmer, as if his decades of pop stardom were a long hallucination. He was also pushing 70, and grappling with death in a way that was not at all symbolic or metaphorical. If Dirt Farmer was a rebirth, it was one where another death, final and uncompromising, waited close at hand. Between his short silence and the inevitable long one—between the vanished South of his childhood and the vanishing world at large—Helm makes his last rebel stand.

Helm’s new record, Electric Dirt, is aptly titled too—he takes the rustic soul of Dirt Farmer and plugs a live-wire into it. Produced by Larry Campbell, it employs the same roster of musicians as Dirt Farmer, who were culled from Helm’s Midnight Ramblers, a sort of ramshackle musical medicine show of the type Helm described to Scorsese in The Last Waltz. An impressive roster of talent is on display—two songs have horn arrangements by the New Orleans R&B legend Allen Toussaint, and two more have arrangements by Sex Mob bandleader Steven Bernstein. With a blend of covers and originals, Helm produces a remarkably thorough self-portrait of a personality so intractable it seems hewn from stone, a natural land formation.

A duo of tough, raucous Muddy Waters songs, “Stuff You Gotta Watch” and “You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had,” cover Helm’s fixation with sweet girls who’ll do you wrong, not to mention his desire to lay off the heavy stuff sometimes and just kick up tourbillions of feathers and sawdust. The Grateful Dead’s “Tennessee Jed” polishes up his working-class bona fides. He reckons with his death, in the humble but unbowed manner of late Johnny Cash, via a rawboned gospel take on the Staple Singers’ “Move Along Train,” and closes the album with a joyful cry against all that binds him, in an upbeat version of “I Wish I Knew How it Feels to be Free,” made famous by Nina Simone. After a lifetime in music and a humbling brush with death, Helm doesn’t seem to compete with the original versions, as can happen with covers—he fully inhabits them, makes them sound like his own. His version of Happy Traum’s “Golden Bird”, croaked out mountain-style over a dragging fiddle, just breaks your heart.

This only leaves room for a few originals, but Helm fits everything he needs to say in them. One, in particular, is too good, too perfectly Levon, not to discuss at length. This is “Growing Trade,” a lament for the plight of working farmers in a time when land is more of a commodity than a site of holy vocation. The song is circumspect, with images of encroaching lawmen, greedy bankers, and the summer beauty of the cotton fields all mixed into one plangent mass. When Helm sings, “I’m half the size that I used to be/ and half of that is stone,” he’s speaking for himself and the land; there’s no difference. There are hints that he’s singing about growing marijuana: The chorus goes, “I know the law won’t be forgiving/ but that is the choice I made/ I used to farm for a living/ and now I’m in the growing trade.” The questions this raises are huge and unsolvable—what does it mean to love the land, if you have to degrade it to keep it? And what does a child of the land do when the land is no more? “Granddaddy said that harvest time was what the good Lord made us for/ I guess he’d wonder, where’s the dignity in a crop you raise to burn?/ But this land is my legacy, I’ve got nowhere else to turn.” This sheds some light on why Helm seems so sanguine about his mortality on songs like “Move Along Train”—he’ll be finally, unambiguously delivered back to the land that has so eluded him in life.