Letter from London

12.08.07

I moved to Europe twenty-five years ago to get away from California. And now I think almost constantly about moving back. Go figure.

I moved to Europe twenty-five years ago to get away from California. And now I think almost constantly about moving back. Go figure.

This is not because I have ever stopped loving London, the first city in the world that made me feel at home. It’s more that I have lived here so long that I can now hate it with all the calm conviction of a native. When I “whinge” about the crowded streets, the corrupt middle-class professional culture, the smarmy government, or the bad sandwiches (yes, you can still find them), I like to think that I don’t quite sound like an Ugly American. I like to think that I sound like an Ugly Brit.

Not that this makes me very palatable to the English. But then, let’s face it—nobody’s very palatable to the English. Which is probably why I get along with them so well.

Unlike Californians, the English keep themselves to themselves, if you know what I mean. They don’t hastily tumble across whatever social or interpersonal boundaries stand in their way, flinging open doors and cupboards, sniffing behind curtains and settees. What’s more, they don’t smear you with their messy interiority, confessing their deepest dreams and aspirations at the drop of a hat. Like puppies (and I have to confess there’s a lot of this puppyishness in my nature as well), Californians are too confident in their enthusiasms. Then, when the world surprises them with something unpleasant, they don’t take time to understand it. They just bite.

In California, you can find yourself talking to people for hours about who they really are, and how they really feel, and how their sense of cosmic self-hood often conflicts too much with their spiritual values and so forth, but you never have any idea what they’re talking about. Once it gets out of the cage, this inner life of Westerners just multiplies exponentially, like that invading space creature in The Blob.

When I decided to make London my home in the mid-eighties, it was still very deeply English, both for good and bad.

When I decided to make London my home in the mid-eighties, it was still very deeply English, both for good and bad.

On the debit side: there were few decent moderately-priced restaurants; you couldn’t buy Ben and Jerry’s ice-cream anywhere; and on bank-holiday weekends, almost every shop closed for two or three days, I’m not kidding. You couldn’t buy a pint of milk unless you took a double-decker bus from one end of the city to another, and wiped the dust off the last UHT-impregnated long-lasting waxy-cardboard container of milk in back of a cluttered news agent shop. For many years, I lived in a tiny converted studio flat that I purchased (during one of London’s mega-perilous housing bubbles) not far from the now-infamous Finsbury Park Mosque. This was a largely West-Indian neighborhood, and about three or four doors down from the local Tesco you could find cow-heads hanging outside on hooks (if, that is, you were looking for them). I remember when the first American-style 7-11 opened over the hill in Crouch End, back before the neighborhood was over-run by movie actors and rock producers. At that time, you could still find people living in the area who did something useful––carpenters, plumbers and so forth––and when I’d trek over Crouch Hill in the middle of the night to this bright and spangly “convenience store,” it felt like journeying to Shangri-La. There I’d run into guys who’d recently fixed my central heating or rerouted my fuse box, and we would marvel at our sudden collective ability to buy things like light-bulbs and donuts at three o’clock in the morning, even on a Bank Holiday weekend. But then the new shopping laws came along, and 7-11 disappeared, replaced by more and more various late-night and weekend outlets. Today, there’s a 24-hour Tesco around the corner from my home in Russell Square, which is constantly packed by jet-lagging American college kids indulging their Krispy Kreme habits. Sure, it’s convenient, but it’s not the same as Crouch End at three in the morning. At that time, being able to buy something late-night in London was like keeping a beautiful secret. Well-lit, unguarded, and pristine.

There were a lot of things I loved about British London in the mid-eighties, even what is often derogatorily referred to as “English cooking.” Such as the British fry-up at a local “caff,” which is, to my mind, one of Britain’s least-recognized culinary innovations. When Brits go fatty, they go really fatty, and I can’t tell you how pleased I was to order my first “English breakfast” and be served both a pair of deep-fried British sausages (the best sausages in the world, to my mind) and bacon and eggs and thick-cut deep-fried chips, and even, I swear to god, a thick lardy slice of what they call “fried bread,” which is definitely the least nutritious (and most satisfying) way of serving bread in the history of, well, bread. Then to see this heart-stopping fat-fest dripping in really runny baked beans and buttery mushrooms, with a large cup of greasy-looking tea on the side––my mouth waters just thinking about it. It’s still my favorite breakfast in the entire world. Also, I don’t know why this is true, but if you decide to seek out one of these very anti-Surgeon-General-type breakfasts on your next trip to the Isles, I have one decent piece of advice (and most of my advice, by the way, sucks): the crummier the caff looks, the better the breakfast. I don’t know why that is, but it definitely is.

Then, of course, there’s British ale, which is the best beer I’ve ever known. I actually sip the stuff a bit like wine, which makes me look like a dilettante when I’m sitting with my book in the back of the dullest, quietest pub I can find. Another interesting thing I’ve learned is that British ale must be drunk out of pint-sized glasses. This doesn’t mean you can’t order a half pint at a time, but it simply must be poured into a well-toned pint-sized glass. It has something to do with how the fragrance is spun off by the large blobby mouth of the glass. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about. If you drink good British ale out of a half-pint glass, you’ll be bitterly disappointed.

Oh, and now that I think about it, I’ve never actually enjoyed a pint of ale with a British fry-up breakfast. But I’ve seen it done. And perhaps I will enjoy this experience one day before I die.

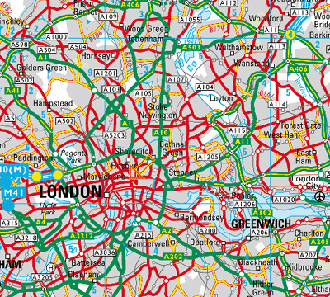

Another thing I loved about London from the start––and this hasn’t changed at all––is it’s belligerent unchangeable eternal sense of rampant disorder and barely-controlled chaos. It’s a city that doesn’t make any sense, either on a map, or in the American conception of things like neighborhoods or city blocks; and it continually spills off in oblique tangents and odd little brick byways and surprisingly-off-kilter flights of stairs, like some mammothly-conceived drawing by MC Escher. In California, I never felt I belonged amongst the wide-open flux of highway-strewn and telephone-line-knitted spaces. But in London, you are instantly grounded in a massy conjunction of time and architecture. History resounds everywhere, but never makes you feel burdened or confined. The only American equivalent would be a place like Los Angeles, with its vast motley of overgrown and discontinuous suburbs. But London has, and always will have, one thing LA never did. Walkable vistas. And in every direction.

Another thing I loved about London from the start––and this hasn’t changed at all––is it’s belligerent unchangeable eternal sense of rampant disorder and barely-controlled chaos. It’s a city that doesn’t make any sense, either on a map, or in the American conception of things like neighborhoods or city blocks; and it continually spills off in oblique tangents and odd little brick byways and surprisingly-off-kilter flights of stairs, like some mammothly-conceived drawing by MC Escher. In California, I never felt I belonged amongst the wide-open flux of highway-strewn and telephone-line-knitted spaces. But in London, you are instantly grounded in a massy conjunction of time and architecture. History resounds everywhere, but never makes you feel burdened or confined. The only American equivalent would be a place like Los Angeles, with its vast motley of overgrown and discontinuous suburbs. But London has, and always will have, one thing LA never did. Walkable vistas. And in every direction.

London is still an awful place for drivers; I’ve never even entertained the thought of buying a car here. Thickly-intertwined by weird one-way serpentine thoroughfares and insane roundabouts and interlocking bike-paths and concrete-barricaded road-works, London is a huge confusion of public and private spaces. In fact, there are still surprisingly large swathes of London that are actually owned by ridiculous things like earls and dukes and such, who rent out their inherited estates to the American universities and foreign banks, much like their multiply-great grand-daddies did many centuries ago. Meanwhile, amidst these old ancestral demesnes, London’s rampant capitalists (and London must be the most fiercely-capitalistic city on earth) have divvied up, subsumed and over-reached every possible loophole in the law—and in spatial harmony—to build radically conflicting intersections of private homes and garden-squares and office blocks and market-stalls. If you ever decide to buy a home in London (and I don’t recommend that you do), you will quickly encounter some of these weird class histories and bowdlerized notions of ownership I’m talking about. For example, the flat you want to “lease” for two hundred and fifty years turns out to be owned by the Duke of Velour, or the Earl of Somesuch, but the wobbly paving stones out front are owned by a long-bankrupted squatter who disappeared during the Blitz, and the backyard tree––the roots of which have invaded your downstairs toilet ––isn’t owned by anybody, so nobody can do anything about it. You never really buy property in London; you only conspire with the mess of history to borrow it for a while. This is probably why, halfway through every property negotiation, your fleet of lawyers and estate agents and surveyors and the seller’s fleet of same collectively agree to disregard at least half of the irresolvable problems they’ve discovered in the multiply-amended deeds and moldy blueprints recently unearthed at City Hall. Otherwise, nobody could buy anything in this town.

So some dead Earl’s tree will always be in deep conflict with some poor slob’s plumbing, that’s just the way it is. At least until another slob (or another tree) moves in to take their place. “Get used to it!”––that’s the British motto. Which is probably why Brits and Yanks have so much trouble seeing eye-to-eye, since the American motto, as we all know, is: “Fix it. Or knock it down.”

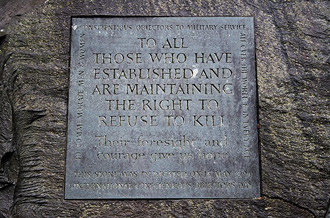

About eight years ago I moved to what I still consider the best part of London, a slice of San Pancras and Bloomsbury that was pretty clearly-demarcated by the bombs of 7/7. One of those bombs erupted deep in the Piccadilly line tunnel that runs underneath my building––where I hear the trains starting up every morning from my bedroom. This rush of underground trains is one of the satisfying sensory impressions that always reassures me I’m home after a long trip abroad, much like the outdoor frying of sausages and onions at Camden market, or the cordite and pigeony ambience of Victoria Station. Another bomb, the one that wrecked the bus at Tavistock Square, went off outside my bank on Southamptom Row, and just across the street from Tavistock Square, where my son, his noisy friends and I use to play squirt gun wars among the well-tended flowerbeds and antiwar monuments––a flower- and garland-bestrewn statue of Gandhi, a tree planted for the victims of Hiroshima, and a large obsidian stone to honor conscientious objectors to military service.

About eight years ago I moved to what I still consider the best part of London, a slice of San Pancras and Bloomsbury that was pretty clearly-demarcated by the bombs of 7/7. One of those bombs erupted deep in the Piccadilly line tunnel that runs underneath my building––where I hear the trains starting up every morning from my bedroom. This rush of underground trains is one of the satisfying sensory impressions that always reassures me I’m home after a long trip abroad, much like the outdoor frying of sausages and onions at Camden market, or the cordite and pigeony ambience of Victoria Station. Another bomb, the one that wrecked the bus at Tavistock Square, went off outside my bank on Southamptom Row, and just across the street from Tavistock Square, where my son, his noisy friends and I use to play squirt gun wars among the well-tended flowerbeds and antiwar monuments––a flower- and garland-bestrewn statue of Gandhi, a tree planted for the victims of Hiroshima, and a large obsidian stone to honor conscientious objectors to military service.

It use to be that many sections of London were noted for their “villagey” atmospheres––the family vendors and outdoor markets and local oddballs––but most of these distinctly-flavorful neighborhoods have been eroded by yuppification, name-brand coffee logos, and tourists. My neighborhood, on the other hand, has retained much of its original flavor over the three decades I’ve been here by doing what Britain seems to do best: throwing its hands up in the air and letting everybody in. All day and night, fleets of tourists escort their castor-squeaking luggage up and down the sidewalks, or sit out in garden squares with their packaged sandwiches and Meal Deals from the local Boots. Sometimes entire classrooms of Italians or Spanish kids swarm up one side of the street, or occupy a coffee shop, and it feels like a benign invasion. But still, most of our local shops and businesses are managed by the same people who managed them seven or eight years ago, though now they commute in from the suburbs, since they can’t afford to live here anymore. Meanwhile, the Brunswick Centre, a former council-estate, has been bought up and redecorated by top-drawer mega-merchants––Virgin, Waitrose and Yo Sushi! Oh no.

I’ve lived in many cities where it actually felt lonely to be alone––but this has never been true of London. It is a disorganized, uncoordinated, sloppy, disjointed, and counter-intuitive agglomeration of buildings where roads are always being torn up in every direction, and every pedestrian crossing feels like the most dangerous place on earth. Nobody seems to know where they are or where they are going, and every other person is feverishly consulting foldable plastic tourist maps or A to Zeds while looking more confused by the second. I can’t blame them, either. After twenty-five years in London, I am constantly surprised by its depths, its diversions, and its interconnectivities. You turn a familiar corner and find yourself in a place you’ve never been before. Or abruptly realize that this bit is actually connected to that other bit you thought was miles away. London is like constantly being lost and found again. You walk into a strange conjunction of dilapidated buildings, turn a red-brick corner, and suddenly find yourself home.

So while I still feel California calling––the blue winter skies and wide-open spaces––I don’t think I could leave London now if I tried. No matter how many flights I booked or trains I caught, I’m pretty sure I’d only be mysteriously tossed back again and again, like that guy in The Truman Show, eternally at home where I never belonged, waking up every morning to the same clocking clatter of trains underneath my bedroom, and the same outdoor smell of sausages.