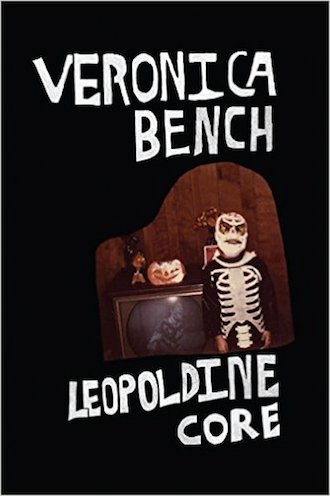

Leopoldine Core’s Veronica Bench

08.09.15

Veronica Bench

Veronica Bench

by Leopoldine Core

Coconut Books

$18 / 170 pp

Pop Corpse, Lara Glenum’s rollicking feminist allegory of “The Little Mermaid,” opens with the disclaimer, “THIS POEM IS MY VOCAL PROSTHESIS.” As the story goes, the mermaid barters her vocal chords for a human body and is left to wander mutely in search of her prince. But in Glenum’s rendition, the mermaid (who’s really after a human orgasm) never sacrifices her audibility. Instead, she wields the poem as a dialogic organ with which she keeps speaking, naming her desires and making demands of those around her. Since reading Pop Corpse, I’ve been infatuated with the idea of poem-as-prosthesis: its inky little speech-acts, its promise of reactivated subjecthood.

The poems in Leopoldine Core’s Veronica Bench are such prostheses. They move in the associative loops and discursive rhythms of conversations, voicemails, and irreligious prayers. Yet, often at the moment when a poem is most parlando—when it is most convincing as a vocal simulacrum—Core hypes its textuality. “[L]ook at the sky / look how red it is,” she writes. And then: “No sunset makes its way / into print.” As readers, we are confidants and onlookers by turns. We follow Core down trompe l’oeil tunnels just to skin our knees on painted walls.

“VIDEOTAPE” is a stunner, and it’s also a microcosm of VB: every line alludes to a theme explored and interrogated elsewhere. Like all these poems, “VIDEOTAPE” is buffered by capacious white space; double-spaced with ragged line-breaks, it wanders between memories and registers, opening with a concrete observation that quickly gives way to an epistemological one:

Here is an egg at the window

Here is my bobcat head on your knee

Here I am staring past you at a memory

I’m squinting because it’s true

that writing ruins memories

melts and replaces them.

While here, the “egg at the window” is probably a sunset, eggs recur throughout these poems, each instance suggesting a few more shades of connotation. From “MORNING COCKTAIL:” “I looked away / from the eggs and tipped / into a tiny film / of someone’s dick.” From “CHARMS:” “I want to have my ovaries removed / and wear them like earrings.” Eggs also collocate with farm animals, with which this book is packed—in “EGG,” two goats push their goat daughter in a carriage; in “MY BABY,” the speaker gives birth to a tiny horse. Lindsay Lohan has an udder, a tender lover is a lamb, pigs are eminently fuckable. Core knows that everyone is an animal, but she knows that women are farm animals: domesticated for consumption, teeming with commodified fertility.

If the archetypal farm is prosaic and safe, Core’s is an abject paddock in a constant state of postcoital dampness. One of VB’s central jokes—and it’s full of jokes—is the queering of some normative scene, the insertion of a dick where we’ve been led to expect a pussy, the sandwich “suddenly…full of cum.” Take for example the next chunk of “VIDEOTAPE:”

I have one now in my mouth

something soft and defaced from 1998

I was young so there was

plenty of room

for him.

I was a purse

I once wrote.

He liked females

but needed men.

They were always huddling

around the fire in awe of each other.

One of them owned a video camera

and he taped me squatting over a

hole in the earth—there’s a video somewhere

of the hour

I am now gutting

with text.

But I remember him

holding the camera.

And I remember

the love

beating

between them.

The big male gaze like a sunset

pouring onto another man.

I remember being naked

in the woods

and actually very turned on

and thinking straight men

never get over their homosexuality

because they never acknowledge it.

All of them sniffing around

for a purse.

Part of what’s compelling about Glenum’s proposal of the poem as a vocal prosthesis is that the text becomes both corporeal and ecstatic—laryngeal in theory but ultimately neither in nor out, here nor there. Queerness is like that: it’s a sexuality whose taxonomic liminality means it’s always writing itself, surprising itself, revising according to its own desires. In the above passage, Core unmasks the libido effervescing beneath of the surface of events— events not inherently sexual, and a libido not inherently hetero-, homo-, or even anthro- sexual.

And the symbolic purse is stuffed with polysemic potential: it’s a feminine accessory, a vessel for cash, a verb for what mouths do before a kiss. Obviously vulvar, it’s Joyelle McSweeney’s “bejeweled purse…a pearled vagina,” Ish Klein’s “recycled sheepskin wallet” from which “womb/vagina sets” are made. Gertrude Stein’s purse “was not green, it was not straw color, it was hardly seen;” “purse strings” metonymize the control, generally by men, of an organization’s expenditures, etc., etc. The lack of punctuation between the implicit quotation “I was a purse” and the exposition “I once wrote” allows “wrote” to predicate both/either the clause and/or the isolate noun—the second, more interesting reading suggesting that Purse is writable, that its field of associations—vagina and woman and money and power—are themselves linguistic productions. When Whitman “sings himself,” he invokes an exophoric self (simulation), but he also produces a self via song (simulacrum). Likewise, the purse. And since “I once wrote” refers to an unspecified point in deictic time, we can read the act of writing either as having already happened, circa 1998, to be duplicate years later in this poem, or as happening only synchronically, in the previous line, which Core necessarily “once wrote.” In other words: I’m a clitoral cash-sack, and I just wrote that.

I’m pointing here to the ways that Core’s koan-like phrases, so concise and seemingly declarative, come easily unsealed. I’m pointing to the ways that all language opens and distends under a little pressure, maybe more the more colloquial the language is. How often do we replay a conversation in our heads, discovering new implications, weighing possible intentions? Core’s gnomic verse demands the same obsessive analysis, and it takes the weirdness of language as one of its major themes.

Many of the poems in VB are fewer than six lines long. Among my favorites are “WEIRD AIR:”

time feels full

but it’s not full

it’s full of fear

and “BIRDS COME HERE:”

to shit

well

just one

hawk

These short poems are jokes and eavesdroppings. They’re mantras and mondegreens, and they make no move to reconcile their internal contradictions. Toward the end, “VIDEOTAPE” veers back into ars poetica, fleshing out the origin story of Core’s epigrammatic style:

Someone wrecked by drugs

but new too.

I never wrote then

but I would imagine

writing. I would imagine

the words and let them dissolve.

PLEASE INCLUDE

YOUR DAUGHTER

IN YOUR VISION

OF HER

and the sound

would

stupidly

stay in my head

like a t-shirt

or a sticker on a car.

It’s hard to believe I was her

and now me, walking around

with a skull full of videotapes.

It’s hard to believe I could

love a man who loved

a little girl.

While this poem is set largely in the past, no one should mistake Core’s interest in personal etiology for nostalgia. She mines history for the same reason she interviews God and preps theatrically for death: to expose the tyranny of those offending institutions—of religion, patriarchy, capitalism, the doomed and leaking body—and with every kiss-off, sap a little power for herself. Core’s pervasive “you,” which refers at first to an ex-partner, balloons over the course of the book to encompass everyone and everything that threatens to breach the speaker’s porous subjectivity. And as the pronoun’s referents multiply, the speaker’s animosity must cleave as many times, shrinking, defusing, turning on itself until “you” is inseparable from “I,” and the refrain of the early poems (“You’re gonna die too”) morphs into the book’s last line: “It won’t be the perfect time. I’ll die.”

“Am I free?” asks Clarice Lispector in Água Viva. “There is some thing still holding me. Or am I holding it? It’s also this: I’m not entirely unbound because I am in union with everything.” Core’s forte is putting into demotic language her subordination to the forces that hold her, through which articulation she becomes the holder: a vulgar, soggy god. Dually poet and poem—subject and object—she asserts her everythingness, converses with the Reaper, and claims her imperfection as her muse. “[L]imitation is good for poetry / the waning apocalypse is good for poetry.”

And while not all of VB’s poems are VIDEOTAPEs (some shift erratically between minimalism and excess, and a couple taper off in a protracted anticlimax), Core’s goal was never formal tidiness. “It’s important, you know / for geniuses / to be sloppy // It makes other people brave,” she charges in “FOUNTAIN.” And following a clichéd metaphor in “OTHER PEOPLE,” she declares, “I know / a bad line / when I see one. // When I write a bad line / I know.” Rather than rewrite it, Core makes the bad line an occasion to revel in the glitchiness and dank homophony of words. It’s this refusal to scrub off the phatic residues of thought and talk that makes Veronica Bench so intimate, so vocative and ballsy. Core invites us to be transparent—and boldly, tenderly, she shows us how.