WWATHYOSTD: Kelly Schirmann & Tyler Brewington on Boyfriend Mountain

11.06.15

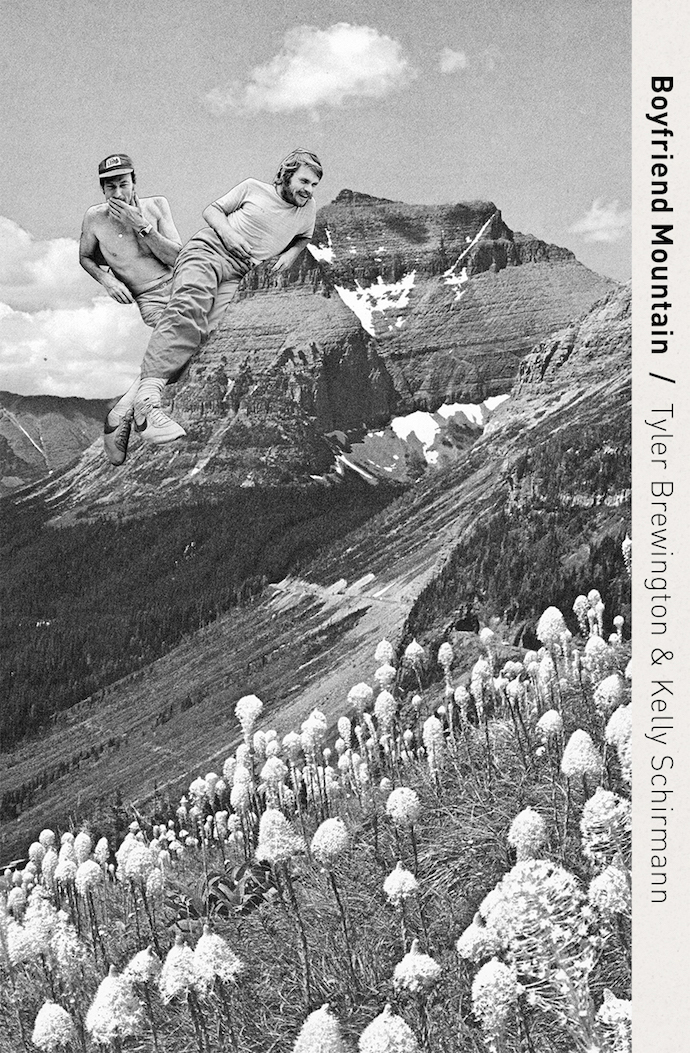

Poor Claudia recently released Boyfriend Mountain, a collaborative tête-bêche written by Kelly Schirmann and Tyler Brewington in which each poet wrote a book of poems called Boyfriend Mountain. Fanzine asked the authors to interview each other about their experiences of writing the book.

Kelly Schirmann: My first question for you is the first question that everyone asks me about the book. Why relationship poems?

Tyler Brewington: When the Poor Claudia team (Stacey Tran and Travis Meyer) approached us about doing a full-length collaborative project, we’d kinda been recently in the shit, relationship-wise, and a lot of the conversations we had when we hung out were revolving around makeouts, breakups, hookups, makeups. Our ideas about romantic interactions had become this wall that was really fun to graffiti over and over again, but it was also a wall we were anxious to see around, you know? We were obsessed with the Big Questions that can only be answered, or partially answered, by knocking your head into that wall: how do I love others, how do I love myself, how do I love the world. The other thing we talked about constantly was poems, so it felt perfectly natural to gather up our equipment and head to the mountain together. If I’m qualified to give any piece of advice in this lifetime it’s this: if you’re feeling curious about your interior life, write about it. Oh, and always be asking: what would a 300-year-old spruce tree do (WWATHYOSTD)?

Also I believe in the appeal of relationship poems, even if I was occasionally nervous about getting really real. Writing about relationships seemed like a great way to lay the foundation for the kind of intimacy we both admire and appreciate as readers. Did you have an ideal reader in mind while we were working on this? Who do you think our book is for?

KS: I want to say this book is for a 300-year-old spruce tree. But additionally, this book is for everyone, and especially for people who are interested in sorting out what it means to be a person. Isn’t it? When we started this project, I know we really wanted to lean heavily into the melodrama of romantic relationships as a kind of exaggerated setting for this sorting out. “In the shit” is exactly how it felt; like everything pertaining to being a human was at once magnified, irritated, supported, illuminated, and destroyed by these relationships. It always feels so intense, so insane, so unbearable when you’re inside of it. It never feels like you can communicate any of it fully to anyone else. It felt important to try to replicate this feeling by pushing the confessional poem form as far into fiction and truth-telling as we could, to shed light on some of these peaks and valleys. So, additionally, this book is for people who get that, and who are willing to go with us down both roads—real and imagined, quiet and exaggerated—as a way of surveying that amazing, unbearable landscape.

I think it’s been a pretty great journey so far, although there have been some things I’ve definitely struggled with (“getting really real” being front and center). What was the hardest part about writing this book for you?

TB: It’s so embarrassing to admit that you care about your life. I don’t know why that is. Now here we have this very public record of how much I care and what caring looked like to me. I tried not to think too much about eventual publication, but I knew we were taking a risk that any writer takes: once a book enters the world, it’s tempting for other people to be like, oh, okay, this person writes this kind of poem. But entering into this dialogue with you felt acutely necessary at the time, and I think I knew I had to write those poems before I could write anything else. For a long time my secret desire was for everyone in the world to buy the book but never, ever open it, and once that passed, I thought, well, at least give me the chance to explain to everyone that I’m not this depressive, mopey, constantly weeping lil’ forest critter. I think what I’m trying to say here is that it was really fucking hard to relinquish all fantasies of control over how the book might be received. It was my job to stay true to the poems and not worry about what might happen to them once they were all alone out there. I guess I already started talking about this, but what do you think is the hardest part about sharing the book, or now sharing the world with our book?

KS: Totally agree. I think the hardest part about sharing this book is/was/always will be the hardest part about writing it as well: not only is it difficult to admit that you care about life, it’s difficult to admit that you are also totally devastated and enamored by life. That you are thinking constantly about how you fit into each other, and what the scars and trophies of this process look like. It’s hard admitting that you have kept the scars and the trophies, and that you look at them every day. I worried that, by putting out a book of these kinds of poems, we were running the risk of being strictly categorized as confessional poets, or much worse, poets who trivialized or disrespected the characters inside them. While I am looking forward to being out from behind the microscope of intimacy, I want to defend these poems as methods we employed to understand the world, and to understand ourselves inside it.

I know we’ve had lots of discussion about this in person—how to navigate the relationship between writing and living. To me it feels like one supports the other, or maybe that they are one in the same. To what extent does the thought of eventual poem-making influence the decisions, thoughts, and feelings you’re having in “real life”?

TB: You know how it’s so rude to answer a question with a question? Answering a question with a poem is probably even more obnoxious, but I want to give this one to Adrienne Rich. Here’s #7 from her “Twenty-One Love Poems”:

What kind of beast would turn its life into words?

What atonement is this all about?

—and yet, writing words like these, I’m also living.

Is all this close to the wolverines’ howled signals,

that modulated cantata of the wild?

or, when away from you I try to create you in words,

am I simply using you, like a river or a war?

And how have I used rivers, how have I used wars

to escape writing of the worst thing of all––

not the crimes of others, not even our own death,

but the failure to want our freedom passionately enough

so that blighted elms, sick rivers, massacres would seem

mere emblems of that desecration of ourselves?

I’m that kind of beast and I’ll die without knowing the answers to all of these questions. I am such a monster but can I go ahead and throw the same question back to you?

KS: Yes, and wow. Now and forever it helps me to be reminded that “I’ll die without knowing the answers to all / any questions.” To me, the experience of “real life” feels very much like a long process of reminding myself that I don’t know anything, that I might actually know less as I get older, at least about the kinds of things we are encouraged to know about. The rivers and the wars—what are they? Do words have bodies? Are the bodies different? I have to wonder, because otherwise I would just know. As much as real life is about discovering and then abandoning, remembering and then forgetting, suffering and then moving on, I want my poems to behave in the same way. I want them to be unearthing ancient and useless truths, and then to bury these truths in the yard again to be discovered later. The process of failing, learning, and trying again is so much more helpful to me than being told what to do or how to do it. Maybe I never want to know anything for certain if it means that I will always be trying to figure it out.