Jazzercise Is A Language: In Conversation with Gabriel Ojeda-Sague

06.03.18

My first encounter with Gabriel Ojeda-Sague was through his debut book Oil and Candle (Timeless, Infinite Light, 2016). On a warm Sunday in Oakland, I lay flat on my back in the grass at Lake Merritt, absorbed in the book’s textural and astute treatments of ritual and race. I met Gabe for the first time a year later at a reading in Philadelphia, where I was glad to learn that he was just as smart, generous, and engaged in person as his writing was on the page.

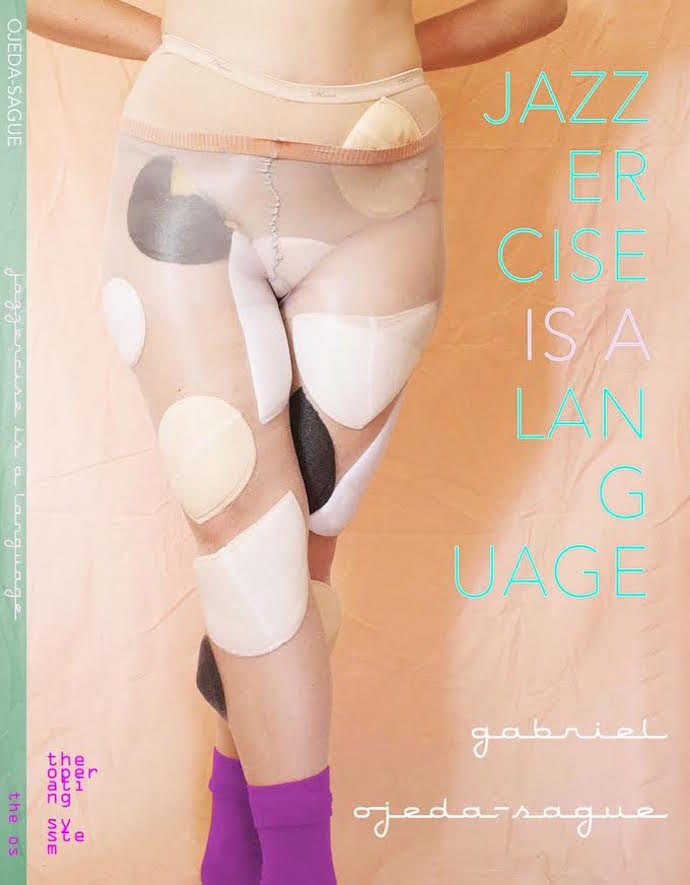

Gabe and I decided to do this interview as a way to celebrate his new book, Jazzercise is a Language (The Operating System, 2018), and to delve deeper into some of the books themes. The book is a long poem about Jazzercise, camp, racial politics, body politics, and feminine strength. As Gabe writes in the book, “the secret is in the derriere, the burning secret, the bushel of flowers” — in this interview I took the opportunity to ask about some of those secrets.

Alli Warren: Your new book Jazzercise takes it name from a fitness franchise I assumed was long gone. But poetry is where I get my news (jk) and I learned from your book that this horrifying American product unfortunately still chugs along. I’m curious how you came to know it? As a kid, I remember rolling around on the carpet watching my mom’s Jane Fonda aerobics tape, but I was born in 1983 and I think you must be too young to remember the ’80s? How did you come to write these poems, what brought you to this particular frame? Another more professional way of saying this is “Gabriel Ojeda-Sague, can you tell me about your ‘research’ process for this book?”

Gabriel Ojeda-Sague: You’re right that I don’t remember the 80s. I was born in ‘94! Please, reader, don’t stop reading now that you know how old I am.

I knew about Jazzercise in a very general sense from the way it was and is parodied in various cultural forums. And growing up as a gay boy, you learn (somehow) about Richard Simmons pretty quickly. But I thought of Jazzercise as a catchy name for any kind of dance aerobics. I had no clue it was a copyrighted name for a specific company, I didn’t know who Judi Sheppard Missett was, and I had never seen the tapes. The way the book starts forming is that I saw a somewhat viral video (I think my brother showed it to me) that was a compilation of funny Judi Sheppard Missett moments. People were saying it reminded them of Kristen Wiig and other quirky high-energy funny women. And I did find it funny, but I also found it oddly convincing and attractive. I just started doing a lot of googling about her and Jazzercise, quickly learning more than a person really should about this company.

I decided it was a viable writing concept when I kept focusing on the specific phrases she was using: “squeeze, tighten, square,” “again,” “feel the burn,” “if you’re smiling, I know you’re breathing,” “it feels good, doesn’t it?” What I felt in them was that they could be read quite ominously. Hyper-attention to the way your body is feeling and being positioned, even if she can’t see you (you only see her, as the case is). When I decided I wanted to tease out what I felt in those phrases, I started writing. After, writing say 15 pages of drafts, I knew I had something viable as a book. I enlisted Julia Bloch’s help to get me a regimented writing and reading schedule so that I could do the book in a timely and concentrated way and not abandon it at any point. And voilà, here we are.

You’re right in saying that Jazzercise chugs along. In many ways it drags along. Taken over by Judi’s daughter Shanna Missett Nelson, Jazzercise has this creepy and antagonistic relationship to nostalgia and its typecasting as an 80s thing. Two recent taglines that explain what I mean: “you think you know us, but you don’t,” and “our only throwback is our right hook.” Yeesh.

AW: No shame in any age, young or old, Gabe! It means we’re alive. Do you know that line in “Hey Ma” where Julez Santana is like “I told her I’m 18 and live a crazy life / Plus I’ll tell you what the 80’s like”? So cute.

That ominous feeling you mention really comes through in the book. There’s a lot of Foucault in those “feel the burn” aerobic phrases. I found myself thinking a lot about the ways that raced, classed, and gendered bodies are controlled and manipulated, appropriated and used up. You mention Jazzercise’s creepy relationship to nostalgia, I wonder if nostalgia always tends to be a bit ominous? The most prominent recent example which comes to mind is Make America Great Again and white people frothing at the mouth to return to some imaginary Leave It to Beaver era. Is there a relationship between nostalgia and biopolitics, or is that too much of a leap?

GOS: In a general sense, it’s hard to say. Certainly we see nostalgia being weaponized constantly in the examples that you give, but I think it’s important to say explicitly that nostalgia requires the invention of a false past there. Once you have a false past invented, you can bounce off of it in intensely emotional or political ways. Those mythologies of the past, in the examples you give, act as springboards into conservative and reactionary political futurity. We sometimes say of nostalgic people or institutions that they are “stuck in the past” but that is not exactly true. They are using a narrative about the past to architect their desired present and future.

You see this acting out on the personal level too. I used to have this ex boyfriend, a very intense and emotional person, verbally abusive, deeply manipulative, who was extremely nostalgic. He would sometimes bring up arguments he had with people when he was in kindergarten, no exaggeration, and tell me about how frustrated he still is with that person and how he still doesn’t understand why they said or did that. Or how he doesn’t understand why somebody stopped being his friend in elementary school. I mean, this was a person who really took stock of every relationship he has had and how it manifested. I don’t think this can be described as being “stuck in the past,” though of course it looks like that, because it was a kind of internal dialogue and thought experiment always going on in his mind to assess his own self-worth and how he relates to the world around him in the now. And being close to him, as a romantic partner, you could feel that internal dialogue externalized in lashing out or extreme passion.

This is all so far away from Jazzercise, but when I think of nostalgia, he is instantly what I think of. But let me recenter myself. What I describe as the company’s weird relationship to nostalgia is how they are always trying to push themselves away from other people’s nostalgia or other people’s images of their brand, while also constantly depending on reference to it. Their current brand is something like “not-our-80s-brand” but it doesn’t actually have its own identity. Which is certainly why they lost out to other dance aerobics trends like Zumba or other video-based exercise trends like P90X and Crossfit.

One last note on nostalgia from me: I was recently watching a Jazzercise video (can you believe I am still watching these occasionally when the book is long done?) and Judi said “oh, to have an 18 inch waist again.” We can easily assume that many of the people who used these videos never had an 18 inch waist after the age of 18. I mean, 18 inches? But it sets this verbalized body goal that you are asked to remember, whether you can identify your body in that state or not, and you are asked to achieve it through 30 minute dance workouts. The language of the video is to burn your body down to a proper/past size, to make you fit and to make sure you fit.

AW: I’m curious how this process of engaging with Jazzercise and its language affected you? Did it excise something? Did the process of writing the book change you? Did it teach you something about your own nostalgia? Given what you say above, I wonder if the writing was a way of working through the past in order to think about your desired present or future?

GOS: Well, the book comes out of two parts of my identity I wanted to worry. I wrote this at a time when I was having an internal and mostly-private conversation around my gender identity and my relationship to womanhood. I don’t think there’s a term exactly that I can put on my gender identity, but I like genderfluid in certain contexts. Part of the book’s insecurity (the key term of the epigraph from Lypsinka: “‘Cause everything I have in the world has many, many insecurities”) is that dialogue about seeing myself as or not as a woman. And that conversation is also framed by a larger conversation about womanhood in relationship to my life as a gay man. The second part would be racial. A lot of my work deals with a category I disapprove of but live within: “the white latino.” So much of the book sets out to deal with understanding how I, a latino viewer, encounter white bodies on screen doing “samba” steps or “mambo” moves, etc. The book is narrated inside of that scene of me looking at a screen that has a white blonde skinny woman on it. And that’s where the writing and the questions start.

I think the book let me deal with a lot of those identity based questions, especially issues of jealousy and inclusion/exclusion, but whether I am any less or more confused about my relationship to those questions is unclear.

I said recently that I think the point of poetry is to make a climate in the mind where a question can be warmed, an anxiety cooled, or an apparatus bothered. I don’t know if I can say that the book changed me, exactly, but I set out to make that climate and I think my little cloudbuster worked.

AW: I think the book does a great job of experientially depicting your viewership vis-à-vis identity, both fixed and fluid. Can you say more about how you think about the cloudbusting abilities of poetry? Are there other tools in your life you use to create such a test climate, or does poetry feel particularly well-suited for this?

GOS: I think what poetry does really well is give the opportunity to poets to perform thinking on record within the constraints (self-defined) of literary form. Reading poetry lets you interface with that performance of thinking, or maybe simulation of thinking is better-said, which is where that cloudbusting is. Force your mind into a gale, write out a gale in the mind, reader picks it up and interfaces with that gale, decides how to manifest it in their own mind. Is it wrong for me to think of poetry so away from the bodily? I hope not. Many people think of poetry as deeply embodied. There’s even a kind of racialized axis to this where criticism around poetry treats it as if poetry by people of color is more embodied than that by white people. I don’t find that a particularly useful, interesting, or exciting stance. I understand why poetry is a thing of the body for so many people, but it’s never felt that way for me. For me, it’s a simulated hallucination at the bottom of the brain.

In my life the other place I go to for such a test climate is probably video games. They work differently, obviously, and are more obviously physically manifested, but I feel that my mood and thinking patterns are similar inside of video games and poetry. That’s part of the reason why I’ve tried, at certain points, to fuse them. One obvious difference is that you have a more legible visual landscape that you interface with in video games. Poetry certainly has a visual landscape, but one that is more automatic and taken for granted than video games. You sort of always have to take stock of the landscape in video games, but certain readers of poetry (not the ones I like the most, but certain ones) don’t do that. That also comes from my practice of wanting to really take seriously that which people have deemed not serious, which would connect back to the world’s favorite aerobics craze.