Irrational Logic: On Grief, Ritual, and Living Alone

31.07.17

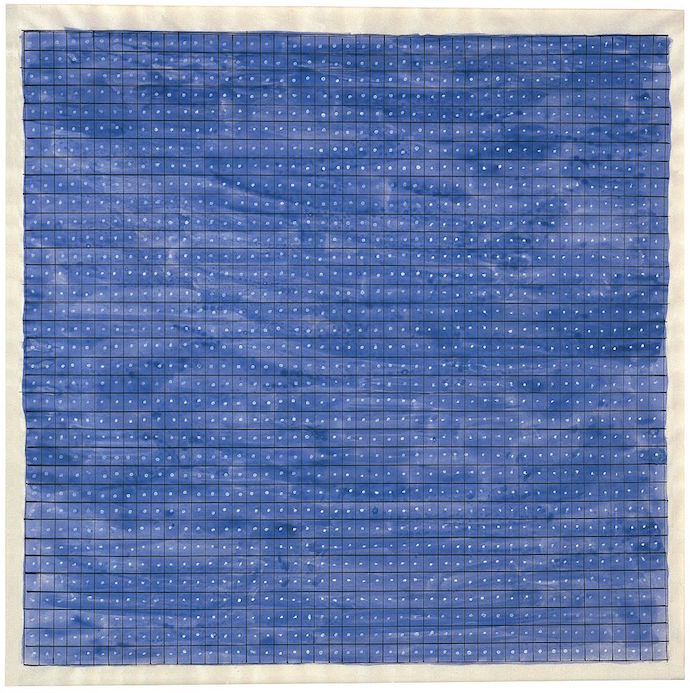

Untitled by Agnes Martin (1965)

In Eve Babitz’s Slow Days, Fast Company, she writes that the best way to get invited out for the evening is to make yourself an elaborate omelet, guaranteeing the moment you’ve finished preparing your meal, the phone will ring with plans to lure you away from your night in. In my own experience, I’ve found that the best way to guarantee someone will die is to screen their call three days prior.

I underline Babitz’s words in fuschia-colored ink, on a Saturday in January, in an apartment I share with no one but my pet cat, Claude. Five months earlier, on a Sunday in August, in an apartment I share with two roommates, my phone rings with news that my father has dropped dead. Or not dropped exactly, as he was swimming at the time it happened. Three days earlier, walking down Broadway during one of the hottest weeks of the summer, I receive a call from my father. I press ignore and continue walking home, careful to stay on the shady side of the street.

This is an irrational logic of course, but I’ve found grief to be a lot of things and rational isn’t one of them.

*

More irrational logic: Two months after my father drops dead, I wake up and decide I need to live alone. A week later, I have found an apartment. Three weeks later, I am carrying the contents of my former bedroom up a flight of stairs into my very first apartment all my own.

*

For the first month living in my new apartment, my body no longer exists. Or, in other words, I don’t own a full-length mirror. Atoms are rearranging themselves in the universe; some things exist more than ever before, some things exist less than ever before. There is definitively less of my father in the world. He has become absence. Or, in other words, as Rachel Zucker puts it in her poem “[taking away taking away everything]” he “is (I am not exaggerating) bone fragments and ash.”

In the poem, Zucker writes about visiting an exhibition of Matisse’s paintings at the Met, both before and after her mother’s death. When she first visits the show, she loves it. After the death of her mother, Zucker visits the show again and can “only see and feel loss—the losing, the erasure, the rubbing out, the flattening.”

I think of Zucker’s words as I hang the remnants of my life on the walls of my new apartment. The things I decided I could not live without when I was packing up for the move. After moving in, I am surprised that many of the things I brought with me I no longer have any desire to fill my new apartment with. Things that had once seemed so fundamental to how I would arrange my life go into the wastebasket.

I think of Matisse’s paints; I think of my father. He is gone—or, in other words, he is what is taken away: revision. I think of Zucker’s lines, “How do you know someone asks when a poem is finished?”

*

In the weeks following my father’s funeral, I find myself stuck on a word: “totally.” It sounds ungraceful and hyperbolic, but it’s the one that keeps arranging itself in my mouth, forcing its way out. As in: Dad is totally dead. Dad is totally not alive. Dad is totally not alive anywhere in this world right now. Maybe the word I was looking for was “definitely,” but what I said was “totally.” As in: My dad will totally never find out who wins the presidential election. I guess I was thinking of the word “infinitely” too. I had known that life was finite, that everybody dies, but I had never considered the inverse: that death was totally infinite. Or maybe, instead of “totally,” the word I was looking for was “finished.” As in: “How do you know someone asks when a poem is finished?”

As in: the end. As Babitz writes in “Rosewood Casket,” “Death to me has always been the last word in people having fun without you.”

*

What I didn’t mention is that I once saw Zucker read “[taking away taking away everything]” in a brownstone in the West Village when my father was still alive.

What I didn’t mention is that when my boyfriend asks who my mother’s favorite artist is, I say Matisse.

What I didn’t mention is that when my boyfriend comes to stay at my mother’s house the week of my father’s funeral, he brings my mother a book of Matisse’s cut-outs as a gift.

*

On a July day when the summer still feels endless, my mother and I take a Metro-North train to Dia:Beacon. Our seatmate for the duration of the trip is a tiny grasshopper who clings to the window. We joke that he is taking the train out of the city for a weekend escape. We plan to take him with us when we get off the train, but when our stop arrives, we forget and leave him behind.

Inside the museum, we stare at sun-washed walls hung with Agnes Martin’s sherbet-colored stripes and admire her dedication to repetition. Line after line meticulously drawn; fields of color blooming into dense grids upon closer inspection. The paintings have names like “Love” and “Happiness” and “Where Babies Come From.” It’s the type of painting you have to let swallow you whole.

That day my mother is wearing a striped skirt in the same shades as one of the paintings. We laugh and I take a photo of her next to the canvas. This is the last time I will see my mother while my father is still alive.

*

Alone in my apartment, while reading Roland Barthes’s Mourning Diary, I bump up against a familiar word: “totally.” As in: “Now, from time to time there unexpectedly rises within me, like a burning bubble: the realization that she no longer exists, she no longer exists, totally and forever.” I feel the sharp knife of recognition twist. Absence where there had once been presence—pencil mistaken for ink. Or as Zucker writes, “This is the end I thought but it was already over.”

*

On a Saturday in November, I go to an Agnes Martin exhibition at the Guggenheim. I follow the building’s curves, looking at canvas after canvas of lines and grids. I’ve always loved Martin’s work, but today I feel oppressed by her steady hand and precise pencil. I’ve been unable to focus on anything for months, and the exhibition’s grand scale and emphasis on concentration feels more like a taunt than an invitation to engage. Just the thought of drawing a straight line feels impenetrable.

I think of Zucker’s words: “What I like I used to say is process when there were still things I liked.”

Rather than appreciating the exhibition, I am distracted. Distracted by a man clearing his throat and standing too close to the paintings. Distracted by the perfectly white sneakers of tourists yielding selfie sticks. Distracted by the lines of my own life having become such a tangled mess.

I buy a print at the gift shop, hail a taxi, and hang the print above my couch—the only place that feels safe enough to allow myself to look straight at it. I tell myself the print is a promise that someday I’ll be able to appreciate things like this again.

*

In “Since Living Alone,” Durga Chew-Bose writes, “Living alone, I soon caught on, is a form of self-portraiture, of retracing the same lines over and over—of becoming.” Living alone is ritual: a repetition of accidents; accidents that become habits; habits that become who you are when no one else is watching. I think of Martin’s hand, confident and focused, tracing line after line. I think of Sunday mornings alone in my apartment.

I think of all of this while making chamomile tea, or lighting a candle. The rituals of solitude. The daily maintenance of a self without an audience. I think of what Roland Barthes wrote on an index card after the death of his mother: “I have not a desire but a need for solitude.”

I think of the rituals I have created for myself here. The routines I have stumbled into. I think of making coffee in the morning. I think of being a daughter of a father. I think of locking my door each night. I think of Matisse’s cut-outs. I think of cutting out the edges of how I define myself with a pair of scissors, careful not to snip away any of the important parts. I think about writing this. How it’s the same thing, really: trimming away the excess to get it all down the way I want it. I think of the endless revision of becoming who you are.

Mourning Diary itself is a project born out of habit; the revision of entire days condensed to a few lines on a scrap of paper; a ritual of the every day. On one slip of paper, Barthes writes, “In taking these notes, I’m trusting myself to the banality that is in me.” That is what living alone is: trusting yourself to the banality that is in you. That is what grief is: trusting yourself to the banality that follows a pair of scissors being taken to your life.

*

In the bedroom where I spent every other weekend for much of my adolescence, there was a print of Matisse’s “The Parakeet and the Mermaid.” I don’t know where it came from, or when it showed up, but it hung above my desk at my father’s house. I used to stare at it the way you stare at clouds. There was the parakeet and the mermaid, of course, but I was always trying to figure out the other shapes. I settled on the idea that the parakeet and the mermaid were surrounded by seaweed and dozens of little blue apples.

I had always assumed the print was the same size as the original. It wasn’t until years after I had last spent a weekend in that room that I realized the true scale of the piece. Matisse had spent the last decade of his life constructing massive memorials to the ritual of cutting away.

*

Things I have cut from this essay: how much I hate swimming; paranoia that I’ll accidentally leave my stove on; antidepressants; the golden toilet also on display at the Guggenheim that day; missing my boyfriend’s birthday for my father’s funeral; the flowers my friends brought to my apartment when I first moved in that I kept long after they had wilted.

It’s all still here, of course, whether or not I write it down. My father is still my father, but an absence in place of presence. Agnes Martin said of her work, “My paintings are not about what is seen. They are about what is known forever in the mind.”

“How do you know someone asks when a poem is finished?”

In an apartment I share with no one but my pet cat, Claude, I make myself an omelet and wait for the phone to ring.