Ideal Home Noise (4): Chytilova, Ocampo, Bourgeois

12.11.15

The fourth installment in Jeff Jackson’s monthly column for Fanzine, Ideal Home Noise, in which he rounds up some of the more compelling recent releases you should think about letting loose in your world. – ed.

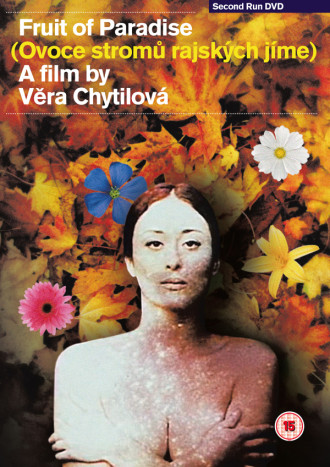

FRUIT OF PARADISE

A film by Vera Chytilova

(Second Run DVD)

The Czech New Wave was one of the most exciting film movements of the 1960s–and it was largely unseen in the West. The filmmaker whose work burned brightest during this brief heyday was Vera Chytilova, who fused pop art visuals, punk energy, mythic tropes, and feminist politics. She’s best known for Daises, an anarchic farce featuring two young women upending polite society that’s a precursor to Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating.

The Czech New Wave was one of the most exciting film movements of the 1960s–and it was largely unseen in the West. The filmmaker whose work burned brightest during this brief heyday was Vera Chytilova, who fused pop art visuals, punk energy, mythic tropes, and feminist politics. She’s best known for Daises, an anarchic farce featuring two young women upending polite society that’s a precursor to Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating.

While Daises has attained cult classic status, her even more radical follow-up Fruit of Paradise (1969) is mostly unknown. Hopefully that will change with the release of Second Run’s beautifully remastered and newly subtitled DVD, which for the first time properly showcases the film’s ravishing visuals.

Fruit of Paradise pushes both form and content to the brink of abstraction, opening with a hypnotic, kaleidoscopic prelude about Adam and Eve that’s reminiscent of Stan Brakhage. Set in a modern-day spa, the main story revolves around a troubled marriage and its potential betrayals. Although the film continually touches on an Edenic theme, it never lapses into easy symbolism. The images of fruit reappear in such different contexts that they pile-up of a dizzying profusion of possible meanings. The episodic narrative brims with absurdist humor and playful gags, but it takes a back seat to the kinetic color-saturated visuals and inventive score. The film rewards multiple viewings, inviting you to piece together the intriguing narrative–this essay by Matthew Revert does a nice job teasing out the various story strands and connections.

Though it heralded from the Eastern Bloc, Fruit of Paradise remains wilder than any contemporary commercial feature made in the West. It highlights Chytilova and her key collaborators – cinematographer Jaroslav Kucera, composer Zdenek Liska, and screenwriter Ester Krumbachova – at the peak of their artistry.

Though it heralded from the Eastern Bloc, Fruit of Paradise remains wilder than any contemporary commercial feature made in the West. It highlights Chytilova and her key collaborators – cinematographer Jaroslav Kucera, composer Zdenek Liska, and screenwriter Ester Krumbachova – at the peak of their artistry.

Shortly after they completed it, the Prague Spring crumbled, the Soviets invaded, and the New Wave evaporated. Their strange masterwork was temporarily swallowed by history, but it’s reappeared undigested and undimmed.

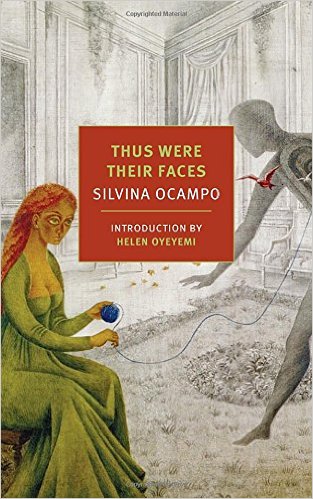

THUS WERE THEIR FACES

By Silvina Ocampo

(New York Review of Books)

Praised by luminaries such as Italo Calvino, Jorge Luis Borges, and Cesar Aira, it’s surprising Thus Were Their Faces is the first major release in English by Argentinian writer Silvina Ocampo. Overshadowed in her lifetime by her sister Victoria, publisher of the journal Sur, and her husband, novelist Adolfo Bioy Casares, Ocampo’s own work has steadily grown in stature. It subtly sleepwalks the line between the mundane and the fantastic, gothic tales and modernist meta-fictions.

This New York Review of Books collection includes 42 short stories drawn from seven books that span her career, selected and translated by Daniel Balderston, who worked with the author before her death in 1993.

The many highlights include the novella “The Imposter,” a tale of continually shifting identities and identifications whose revelations about a budding friendship surprise and unnerve in equal measure; the eerie and melancholy “House Made of Sugar”; and the supernatural folk tale “Leopoldina’s Dream.”

Some of Ocampo’s stories only last a few pages, but they’re still slippery and difficult to pin down. In “The Clock House,” acts of spectacular cruelty are deftly concealed between the sentences. Ocampo’s prose is occasionally plain and her narratives sometimes strain for surprise endings, but the overall effects she achieves are beyond mere craft.

Her stories evoke a sensation that’s hers alone, infecting the rituals of everyday life with a casual and uneasy surrealism.

Her stories evoke a sensation that’s hers alone, infecting the rituals of everyday life with a casual and uneasy surrealism.

Her narrators know how to hear mythic underpinnings in the rustle of an old velvet curtain and revel in the secret, ambivalent, and occasionally abject life of household objects.

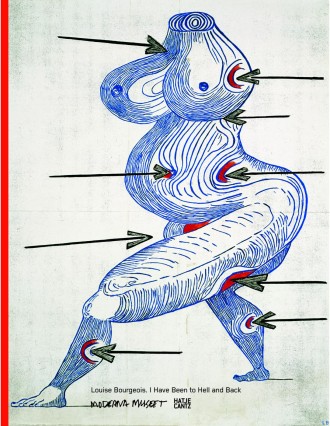

LOUISE BOURGEOIS – STRUCTURES OF EXISTENCE: THE CELLS

(Prestel)

LOUISE BOURGEOIS – I HAVE BEEN TO HELL AND BACK

(Hatje Cantz)

Since her death in 2010, the art world has been coming to grips with Louise Bourgeois’s massive body of work, which oscillated between the confessional and the readymade, including sculptures, installations, drawings, writings, and textiles. Although her career spanned seventy years, she never followed prevailing trends and did some of her most important and unclassifiable work in her final decades. She described her great theme as “woman from object to subject.” Two new beautifully illustrated books illuminate her art from different perspectives.

Since her death in 2010, the art world has been coming to grips with Louise Bourgeois’s massive body of work, which oscillated between the confessional and the readymade, including sculptures, installations, drawings, writings, and textiles. Although her career spanned seventy years, she never followed prevailing trends and did some of her most important and unclassifiable work in her final decades. She described her great theme as “woman from object to subject.” Two new beautifully illustrated books illuminate her art from different perspectives.

I Have Been to Hell and Back is a career survey that eschews chronology. Instead it’s divided into loose thematic sections–“Loneliness,” “Fragility,” “Nature Studies,” “Eternal Movement,” “Taking and Giving,” and “Balance.” It’s fascinating to see how recurring motifs manifest and mutate over the course of a lifetime. The book places an unusual emphasis on her drawings and textile works. Although these pieces aren’t as memorable as her sculptures, they highlight key facets of her work that have been omitted from other overviews. Rounded out with a personal photo album and a revealing interview, Hell and Back is a welcome addition for fans, though not necessarily the place to start.

Structures of Existence is more essential. It’s the first book to catalog all of Bourgeois’s “cells,” the sculptural installations that remain her greatest achievement.

Created over twenty years, these architectural spaces are constructed from doors, panels, cages, screens, and mirrors – and filled with beds, chairs, tapestries, glass balls, thread spools, dolls, and occasional bits of text, such as “pain is the business I am in.”

The environments invite associations between biography and abstraction, while also being ineffably emotional, their found objects charged with meanings that largely hover beyond the borders of language. The book’s numerous essays trace the gradual development of the cells and explore their multi-faceted forms, but it would’ve been better to include more color photographs of the works themselves in order to capture them as fully as possible. The cells open up new secrets when viewed from different perspectives. Or as Bourgeois herself put it: “Reality changes with each new angle.”