I Think You’re Great: OVERUNDERSIDEWAYSDOWN

17.04.06

For the exhibition “overundersidewaysdown” currently to be seen at the independent QNA (Queen’s Nails Annex) gallery in San Francisco’s Mission District, the curator Margaret Tedesco asked me to meet up with each of the participating artists and provide some critical insight. That seemed like the kind of thing I could handle. She was intentionally vague about the concept and even vaguer about the title of the show.

“When I was young people spoke of immorality,” sang the Yardbirds on their original recording of “overundersidewaysdown” (1965). “All the things they said were wrong are what I want to be.” And when I was young I collected packs of Beech-Nut’s Fruit Stripe gum, the most peculiar gum of the postwar era, for when you opened the white wrapper you saw pastel stripes arrayed diagonally on a stick which, in a ghastly “reveal,” failed to disguise the sickly white underneath, the gum base. Your eyes didn’t know where to look, at the color or its lack. Your conscience tried to make a case for focusing on the color. It was a popular look, not only for kids, not only for circus clowns. Alma Thomas, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland were making color field paintings in which stripes crowded each other like cats chasing their tails, rainbows ran a ghastly riot. At the Silver Factory, Warhol and Malanga and David Whitney were churning out silk-screens of Holly Solomon’s face in lime, orange, lemon, sky blue, with gum white holding the whole thing together. Chewing gum furiously, on speed, their jaws crunching. In the Village the artisans who made tie-dyed T shirts were trying to imitate the psychedelic sprawl of Fruit Stripes. You saw it in the movies too, in everything from Petulia to It’s a Bikini World to Antonioni’s Red Desert, color unleashed, supersaturated, given a chance to exfoliate, to blaze like candy.

Fruit Stripe came in four flavors (though in recent times the range has expanded to 17). Each flavor had its own animal, like the daimons in Philip Pullman’s later fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials. There was “Orange Stripes,” the brazen mouse, “Lemon Stripes,” the demure elephant, “Cherry Stripes,” the cheerful horse, and “Lime Stripes,” the romantic tiger. I used to wonder how the Madison Avenue boys had come up with such counterintuitive choices. Why “Lemon Stripes” for an elephant? Or rather, why an elephant to evoke or illustrate lemon stripes? Forty years later it still doesn’t make sense. I would line up the sticks of gum on my coverlet in bed, and prod them with a finger, making them bow and curtsy to each other, to me. On my little 45 record player The Yardbirds twanged and boasted about their looks. “Cars and girls are easy to come by, in this day and age.” That was enough to make a boy envious, even though I didn’t know what exactly I would do with either a car or a girl. I leaned over, bent at the waist, and licked the wrapper of the cherry-striped gum, thought of a horse. I didn’t know it but what I was seeking, as were all of us in the 1960s, was total immersion in image. Or maybe synaesthesia, in which a flavor like lime would suggest a tiger. You licked it, you chewed it, animals tossed themselves around in your mouth like cats, forever batting each other like fruit. “Over, under, sideways, down, backwards, forwards, square and round.”

Fruit Stripe came in four flavors (though in recent times the range has expanded to 17). Each flavor had its own animal, like the daimons in Philip Pullman’s later fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials. There was “Orange Stripes,” the brazen mouse, “Lemon Stripes,” the demure elephant, “Cherry Stripes,” the cheerful horse, and “Lime Stripes,” the romantic tiger. I used to wonder how the Madison Avenue boys had come up with such counterintuitive choices. Why “Lemon Stripes” for an elephant? Or rather, why an elephant to evoke or illustrate lemon stripes? Forty years later it still doesn’t make sense. I would line up the sticks of gum on my coverlet in bed, and prod them with a finger, making them bow and curtsy to each other, to me. On my little 45 record player The Yardbirds twanged and boasted about their looks. “Cars and girls are easy to come by, in this day and age.” That was enough to make a boy envious, even though I didn’t know what exactly I would do with either a car or a girl. I leaned over, bent at the waist, and licked the wrapper of the cherry-striped gum, thought of a horse. I didn’t know it but what I was seeking, as were all of us in the 1960s, was total immersion in image. Or maybe synaesthesia, in which a flavor like lime would suggest a tiger. You licked it, you chewed it, animals tossed themselves around in your mouth like cats, forever batting each other like fruit. “Over, under, sideways, down, backwards, forwards, square and round.”

That lyric that featured “square and round” was a mild surprise; to me, a child, “square and round” didn’t seem on the same register as the other polar opposites. It made me go back and re-examine my assumptions. After a bit it would dawn on me that perhaps “sideways” and “down” were, after all, not antonyms either. You could save up gum wrappers and mail them in to Beech-Nut and get plush animals back in the mail. I never did this, it seemed too faggy, but oh, how I regretted my—my own indecision, my scruples, my drive away from pleasure and towards a “girls and cars” manliness that meant, essentially, no plush stuffed animals, all of them about the same size, odd, so that mouse and elephant occupied the same space, obliterating the hierarchy of size. A year or so later in the 1960s I started taking the pills that Grace Slick promised would make me larger or smaller at will, obliterating the tyranny of everything being different sizes. When I was by myself I’d pull off my pants and watch my body change in depth, achieve what seemed like a giant size, and make it real by looking at this erection in a hand mirror down by my thighs. It really works, I thought. Backwards, forwards, square and round.

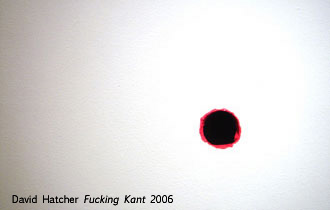

I went to visit David Hatcher in his Culver City studio, part of a cheerless block maintained by UCLA for its grad students. It has the feel of history, like visiting Manhattan Project headquarters. And of course much of the most exciting work of the past ten years in America has issued from this “lab.” Hatcher’s brisk and cheerful, endlessly obliging and personable. I’m sure I didn’t ask him one question he hasn’t answered four or five times before, but he made a bright stab at surprise and interest. Hatcher’s from New Zealand, though he has spent much time in Berlin and LA recently. In his white Gilligan hat and linen shirt of soft blue, he seems utterly at home in a world of high philosophy I have trouble getting to the bottom of. In December I had dropped in at the “Back Room Gallery,” a temporary cache of artists’ source materials organized by Magali Arriola, Kate Fowle, and Renaud Proch. Situated in a nondescript storefront on La Cienega just above Venice, the “Back Room” featured a pair of enigmatic and weighty binders Hatcher had loaned the curators. It took me about an hour and a half of leafing through the materials, to figure out what Hatcher had gone and done. With what I imagine to be the patience of a saint, or someone on a very long grant perhaps, he had taken up residence in a huge library and gone through the notebooks of the philosophers (many of which have been published in facsimile), always with one eye on finding the places where words were not enough and the great thinkers broke out into doodles. You know, like Wittgenstein trying to draw that optical illusion where the figure looks like a duck from one angle, a rabbit from the other? The ‘visual forms of critical discourse in the west’ are, in Hatcher’s translations of them, synaesthetic in and of themselves. Hatcher’s done a clever job of re-drawing Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit and posing it in earnest, intellectual conversation with Hugh Hefner’s Playboy logo rabbit. The two famous rabbits seem as though they’re in some suave cocktail party waiting only for the Pink Panther to arrive, or Ray Johnson I suppose. So much goes unsaid between the duck rabbit and his Playboy counterpart. It breaks your heart.

I went to visit David Hatcher in his Culver City studio, part of a cheerless block maintained by UCLA for its grad students. It has the feel of history, like visiting Manhattan Project headquarters. And of course much of the most exciting work of the past ten years in America has issued from this “lab.” Hatcher’s brisk and cheerful, endlessly obliging and personable. I’m sure I didn’t ask him one question he hasn’t answered four or five times before, but he made a bright stab at surprise and interest. Hatcher’s from New Zealand, though he has spent much time in Berlin and LA recently. In his white Gilligan hat and linen shirt of soft blue, he seems utterly at home in a world of high philosophy I have trouble getting to the bottom of. In December I had dropped in at the “Back Room Gallery,” a temporary cache of artists’ source materials organized by Magali Arriola, Kate Fowle, and Renaud Proch. Situated in a nondescript storefront on La Cienega just above Venice, the “Back Room” featured a pair of enigmatic and weighty binders Hatcher had loaned the curators. It took me about an hour and a half of leafing through the materials, to figure out what Hatcher had gone and done. With what I imagine to be the patience of a saint, or someone on a very long grant perhaps, he had taken up residence in a huge library and gone through the notebooks of the philosophers (many of which have been published in facsimile), always with one eye on finding the places where words were not enough and the great thinkers broke out into doodles. You know, like Wittgenstein trying to draw that optical illusion where the figure looks like a duck from one angle, a rabbit from the other? The ‘visual forms of critical discourse in the west’ are, in Hatcher’s translations of them, synaesthetic in and of themselves. Hatcher’s done a clever job of re-drawing Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit and posing it in earnest, intellectual conversation with Hugh Hefner’s Playboy logo rabbit. The two famous rabbits seem as though they’re in some suave cocktail party waiting only for the Pink Panther to arrive, or Ray Johnson I suppose. So much goes unsaid between the duck rabbit and his Playboy counterpart. It breaks your heart.

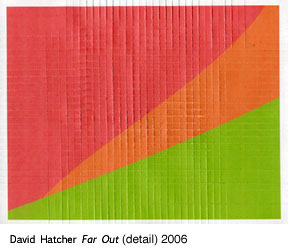

From his binders Hatcher pulls out nuttier and nuttier examples of the sorts of things that the philosophers doodled when they thought no one was looking. Many were bumbling, endearing in their flatness—like the duck-rabbit. Deleuze and Guattari, however, had the bravura and “I’ll show you” bounce of Gilbert and George. Odd. My wife Dodie was with me, craning her neck all around, and she asked Hatcher, “Is this really your studio? It’s so tidy.” For everything was in its proper place and the plain, utilitarian floor was nicely swept. You might have eaten off the floor, perhaps some New Zealand health food, kumara balls or kiwi rocket salad. As it turned out there was another studio where he does the messy bits. His piece is a large reconstruction of a drawing by our contemporary, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who, in his collection The Field of Cultural Production, mapped intersecting cordons of influence in Flaubert’s 1869 novel, L’Education Sentimentale. In the novel Flaubert’s young man from the provinces, Frederic Moreau, finds himself in 1848 in the midst of incalculable pressures from society, from the brokers of marriage, from art dealers, from the military establishment and from his own stubborn wish for mastery. Bourdieu’s map of these intersecting circles is, oddly, squashed, not a circle itself, more of a capsule shape. The way Hatcher has painted it up it looks to me like the old time decongestant Contac. He calls the work “Far Out (The field of power according to Sentimental Education).” Hatcher employs a pharmaceutical range of colors, pink, green, blue, a whitish yellow like ivory. Everything pleasant and easy to go down. If the implications of Bourdieu’s theory are bewildering, we puzzle no more, for in Hatcher’s satirical worldview, thought takes a backseat to image.

From his binders Hatcher pulls out nuttier and nuttier examples of the sorts of things that the philosophers doodled when they thought no one was looking. Many were bumbling, endearing in their flatness—like the duck-rabbit. Deleuze and Guattari, however, had the bravura and “I’ll show you” bounce of Gilbert and George. Odd. My wife Dodie was with me, craning her neck all around, and she asked Hatcher, “Is this really your studio? It’s so tidy.” For everything was in its proper place and the plain, utilitarian floor was nicely swept. You might have eaten off the floor, perhaps some New Zealand health food, kumara balls or kiwi rocket salad. As it turned out there was another studio where he does the messy bits. His piece is a large reconstruction of a drawing by our contemporary, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who, in his collection The Field of Cultural Production, mapped intersecting cordons of influence in Flaubert’s 1869 novel, L’Education Sentimentale. In the novel Flaubert’s young man from the provinces, Frederic Moreau, finds himself in 1848 in the midst of incalculable pressures from society, from the brokers of marriage, from art dealers, from the military establishment and from his own stubborn wish for mastery. Bourdieu’s map of these intersecting circles is, oddly, squashed, not a circle itself, more of a capsule shape. The way Hatcher has painted it up it looks to me like the old time decongestant Contac. He calls the work “Far Out (The field of power according to Sentimental Education).” Hatcher employs a pharmaceutical range of colors, pink, green, blue, a whitish yellow like ivory. Everything pleasant and easy to go down. If the implications of Bourdieu’s theory are bewildering, we puzzle no more, for in Hatcher’s satirical worldview, thought takes a backseat to image.

Each panel of “Far Out” is printed on a particular sort of variegated paper, in perforated squares of about a quarter inch deep. Looks like LSD paper. “So it is,” Hatcher replies with a half-suppressed sigh, as though knowing he has to launch into a long explanation. “Well, it’s blotter paper, there’s a difference.” I take it that vintage blotter paper, with its twinkling suggestion of LSD, suggests further that there are worlds within worlds, all of them highly portable (for LSD originally came in pills, and when criminalized was punished by weight, so that it behooved the dealers to devise a venue for the drug with less bulk). And the feeling of being easily pulled apart, ripped along one’s perforations, was a perfect objective correlative to both the power and the ease of LSD. In grander terms, the drift, the way Hatcher’s piece floats on its separate panels, recapitulates this letting go on a larger scale, doesn’t it? Stretching, he reminded us that Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who invented LSD-25, just turned 100 years old in January. Back in San Francisco, “Dead or Alive?” confirms this—the betting site for celebrities who you never heard were dead. Seems like a lot of them are getting on up there. Oskar Niemeyer’s 98—he designed Brasilia. Claude Levi-Strauss is 97. All these psychic explorers! Mitch Miller, Giancarlo Menotti, Naguib Mahfouz, the list goes on and on, and the yard went on forever . . . . Hofmann’s on crutches, but sharp as a tack, as a recent conference in his honor in Basel showed. “LSD came to me. I didn’t look for it,” he insisted. “LSD wanted to be found. It wanted to tell me something.”

Each panel of “Far Out” is printed on a particular sort of variegated paper, in perforated squares of about a quarter inch deep. Looks like LSD paper. “So it is,” Hatcher replies with a half-suppressed sigh, as though knowing he has to launch into a long explanation. “Well, it’s blotter paper, there’s a difference.” I take it that vintage blotter paper, with its twinkling suggestion of LSD, suggests further that there are worlds within worlds, all of them highly portable (for LSD originally came in pills, and when criminalized was punished by weight, so that it behooved the dealers to devise a venue for the drug with less bulk). And the feeling of being easily pulled apart, ripped along one’s perforations, was a perfect objective correlative to both the power and the ease of LSD. In grander terms, the drift, the way Hatcher’s piece floats on its separate panels, recapitulates this letting go on a larger scale, doesn’t it? Stretching, he reminded us that Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who invented LSD-25, just turned 100 years old in January. Back in San Francisco, “Dead or Alive?” confirms this—the betting site for celebrities who you never heard were dead. Seems like a lot of them are getting on up there. Oskar Niemeyer’s 98—he designed Brasilia. Claude Levi-Strauss is 97. All these psychic explorers! Mitch Miller, Giancarlo Menotti, Naguib Mahfouz, the list goes on and on, and the yard went on forever . . . . Hofmann’s on crutches, but sharp as a tack, as a recent conference in his honor in Basel showed. “LSD came to me. I didn’t look for it,” he insisted. “LSD wanted to be found. It wanted to tell me something.”

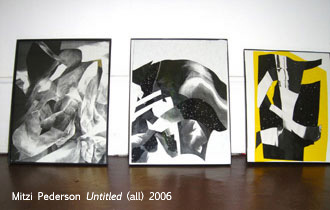

The total immersion in image: while Mitzi Pederson isn’t especially into illustration, there’s a continual tracing of the image in her work, which plays with ideas of tenacity and the delicate, only to mix them up in a gestural roundabout. When I visited her studio last month I pushed my way through a curtain into the space, a curtain devised of black legs of pantyhose each with something heavier, protruding, weighting it down. Maybe the rod attached to the doorway lintel was the most convenient place to store these eccentric objects, these dangling leg-like shadows; or maybe she displays, even on coming in, a concern with the liminal, the edge of things. Part the black gauze, and step into a Victorian room completely covered over with projects in a thousand states of completion. You couldn’t even look, your gaze diverted in a dozen competing directions. (“Just like life,” I told myself, tripping out.) There’s a lot of wood here, I noticed, wood and pantyhose. Later the sculptor Matt Flegle helpfully identified the wood Pederson uses as “doorskin,” thin slices (1/4 inch, or even 1/8 of an inch) of luan sliced and glued together like a pale carpaccio. You see it in cheap movie doors, when a fist is going to fly through one. Pederson uses doorskin for its startling flexibility; it just about curves when you merely hold it in your hands. People use it for dollhouses, birdhouses, and due to cheap glues one side always glints, shiny, sticky looking, like a veneer of hopeful makeup on a streetwalker’s visage. Or like you’ve spilled beer all over it. When we met, Pederson hadn’t yet decided what to do for this exhibition, but one of her ideas was to secure a slice of doorskin and test its tensile strength by dangling something with some heft to it, watch the top curl down like a fragile autumn leaf.

The total immersion in image: while Mitzi Pederson isn’t especially into illustration, there’s a continual tracing of the image in her work, which plays with ideas of tenacity and the delicate, only to mix them up in a gestural roundabout. When I visited her studio last month I pushed my way through a curtain into the space, a curtain devised of black legs of pantyhose each with something heavier, protruding, weighting it down. Maybe the rod attached to the doorway lintel was the most convenient place to store these eccentric objects, these dangling leg-like shadows; or maybe she displays, even on coming in, a concern with the liminal, the edge of things. Part the black gauze, and step into a Victorian room completely covered over with projects in a thousand states of completion. You couldn’t even look, your gaze diverted in a dozen competing directions. (“Just like life,” I told myself, tripping out.) There’s a lot of wood here, I noticed, wood and pantyhose. Later the sculptor Matt Flegle helpfully identified the wood Pederson uses as “doorskin,” thin slices (1/4 inch, or even 1/8 of an inch) of luan sliced and glued together like a pale carpaccio. You see it in cheap movie doors, when a fist is going to fly through one. Pederson uses doorskin for its startling flexibility; it just about curves when you merely hold it in your hands. People use it for dollhouses, birdhouses, and due to cheap glues one side always glints, shiny, sticky looking, like a veneer of hopeful makeup on a streetwalker’s visage. Or like you’ve spilled beer all over it. When we met, Pederson hadn’t yet decided what to do for this exhibition, but one of her ideas was to secure a slice of doorskin and test its tensile strength by dangling something with some heft to it, watch the top curl down like a fragile autumn leaf.

Her constructions, whether in 2-D or 3-D, glow with an ersatz beauty, as though they’ve been through hard times yet they’re still, defiantly, here. In 1998 French fashion photographer Stephane Sednaoui photographed the pop singer Kylie Minogue for the cover of her “experimental” LP Impossible Princess, placing the artist inside a hologram soaked and roofless enclosure, like a surround-sound tent, in which she seemed to dangle and drift amid bands of Fruit Stripe colors, and in Mitzi Pederson’s sculpture something of Kylie’s disconnection from the laws of physics radiates outward, splashing the studio with a poignant glee. From one cluttered wall hangs a large drawing, hot pink paint poured from above to spatter and soak into the white paper. Minutely Pederson has appliqued a powder of black glitter to the individual spatters, so that they become vivid, pointed up, the show piece. Stanley Donen’s Funny Face, with its rueful “Think Pink” number, comes to mind. “Do you mind if I take some photos,” I ask her, like Fred Astaire’s Avedon cartoon in Funny Face. Afterwards, having developed my exposures at Walgreens, I wind up holding a print of a sheet of gold leaf, is what it looks like, and I wonder what it was, or if I’ve gotten my films out of order and this is a souvenir from our visit to Anish Kapoor at Regen Projects. You know how Kapoor’s work is like looking down the throat of Tubby the Tuba?

Her constructions, whether in 2-D or 3-D, glow with an ersatz beauty, as though they’ve been through hard times yet they’re still, defiantly, here. In 1998 French fashion photographer Stephane Sednaoui photographed the pop singer Kylie Minogue for the cover of her “experimental” LP Impossible Princess, placing the artist inside a hologram soaked and roofless enclosure, like a surround-sound tent, in which she seemed to dangle and drift amid bands of Fruit Stripe colors, and in Mitzi Pederson’s sculpture something of Kylie’s disconnection from the laws of physics radiates outward, splashing the studio with a poignant glee. From one cluttered wall hangs a large drawing, hot pink paint poured from above to spatter and soak into the white paper. Minutely Pederson has appliqued a powder of black glitter to the individual spatters, so that they become vivid, pointed up, the show piece. Stanley Donen’s Funny Face, with its rueful “Think Pink” number, comes to mind. “Do you mind if I take some photos,” I ask her, like Fred Astaire’s Avedon cartoon in Funny Face. Afterwards, having developed my exposures at Walgreens, I wind up holding a print of a sheet of gold leaf, is what it looks like, and I wonder what it was, or if I’ve gotten my films out of order and this is a souvenir from our visit to Anish Kapoor at Regen Projects. You know how Kapoor’s work is like looking down the throat of Tubby the Tuba?

It’s not all about contradiction, but a lot of “it” is; Pederson’s work I mean, combining the gray drabness of cinderblock with silver glitter; the light and the heavy, the flat and the sculpted, that which we keep, that which we discard; the ephemera and the cathedrals of old time. “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” Walt Whitman wrote these words, in “Song of Myself.” “I concentrate toward them that are nigh, I wait on the door-slab.” I kept thinking of the TV sci-fi drama Invasion, set in the Everglades after a major hurricane, in which alien life forms invade the bodies of humans, so that the invaded grow gills and can live just as easily under water as they can in their SUVs and complicated private lives, thus swallowing contradictions like air, like water. As in Pederson’s sculpture, everything becomes the element in which it is so exquisitely perched.

It’s not all about contradiction, but a lot of “it” is; Pederson’s work I mean, combining the gray drabness of cinderblock with silver glitter; the light and the heavy, the flat and the sculpted, that which we keep, that which we discard; the ephemera and the cathedrals of old time. “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” Walt Whitman wrote these words, in “Song of Myself.” “I concentrate toward them that are nigh, I wait on the door-slab.” I kept thinking of the TV sci-fi drama Invasion, set in the Everglades after a major hurricane, in which alien life forms invade the bodies of humans, so that the invaded grow gills and can live just as easily under water as they can in their SUVs and complicated private lives, thus swallowing contradictions like air, like water. As in Pederson’s sculpture, everything becomes the element in which it is so exquisitely perched.

Finally I made my way to Dolores Street where, in the basement of the house he shares with media artist Elliot Anderson, Wayne Smith has been making most of the other most exciting work of the past ten years in America. He led me through the converted garage which houses some of his Shaker memorabilia. The Shakers, for those who don’t know, were a Utopian cult founded by “Mother” Ann Lee in 1776; they make lovely furniture, dance in a spastic, trancelike manner to express their love of God, and they never have sex, so there aren’t many of them left around. Four to be exact, average age, I don’t know, about sixty? And here they are, scanned by the artist and subtly distorted, delicate, like the falling feather through which the Shakers have symbolized man’s brief passage through this world.

Finally I made my way to Dolores Street where, in the basement of the house he shares with media artist Elliot Anderson, Wayne Smith has been making most of the other most exciting work of the past ten years in America. He led me through the converted garage which houses some of his Shaker memorabilia. The Shakers, for those who don’t know, were a Utopian cult founded by “Mother” Ann Lee in 1776; they make lovely furniture, dance in a spastic, trancelike manner to express their love of God, and they never have sex, so there aren’t many of them left around. Four to be exact, average age, I don’t know, about sixty? And here they are, scanned by the artist and subtly distorted, delicate, like the falling feather through which the Shakers have symbolized man’s brief passage through this world.

On a desk in a nearby room were scattered dozens of black and white heads of Johnny Carson, the one time king of late night TV, who retired in 1992 after thirty years of “Tonight” (and who died last year). “I used to like him,” I offered. “Sort of.” Smith made no reply, just kept switching his tiny heads around according to how old Carson looked in each photo. In the assemblage as you see it, the king of comedy grows from a towheaded Iowa boy through his teenage years as an amateur magician, and then, all of a sudden, with “Tonight” celebrity, the images multiply like tribbles, and no one viewing can approximate his glory. He was a man more photographed than loved and at the end, barely remembered, he became a wave, a segue, from one form of information to another.

The truth is, we have collaborated over the years on so many projects that if Wayne asked me to run naked down Valencia Street I would do so, but he asked me this time only to stand before a microphone in his makeshift recording studio (“The Basement Tapes” I thought with excitement) and recite from memory the different postures of Tai Chi. “Don’t bother reciting them in order,” he directed, “just say any of them that come to mind.” OK, I could do that. I fixed my gaze on the ceiling and intoned, “Step back and repulse the monkey . . . taking the tiger to mountain . . . grasp the sparrow’s tail . . . single whip.” Several more came to mind later, and Wayne said he would splice them in for his orchestral composition. The finished track, “Cloud Hands,” would form part of his new CD, I Think You’re Great, and would be available at the present exhibition.

The truth is, we have collaborated over the years on so many projects that if Wayne asked me to run naked down Valencia Street I would do so, but he asked me this time only to stand before a microphone in his makeshift recording studio (“The Basement Tapes” I thought with excitement) and recite from memory the different postures of Tai Chi. “Don’t bother reciting them in order,” he directed, “just say any of them that come to mind.” OK, I could do that. I fixed my gaze on the ceiling and intoned, “Step back and repulse the monkey . . . taking the tiger to mountain . . . grasp the sparrow’s tail . . . single whip.” Several more came to mind later, and Wayne said he would splice them in for his orchestral composition. The finished track, “Cloud Hands,” would form part of his new CD, I Think You’re Great, and would be available at the present exhibition.

Then there are thirty small drawings: tiny surfers try to tame big waves in each photo, and Smith’s demonic, Orwellian grid blocks them out of natural sequence, so that forever frozen they are caught, wiping out—and being wiped out by Smith’s pencil—in an endless loop of temporal space. “Okay, so let me free associate for a minute,” I told him. Resigned, he slumped in a chair leaving me room to prattle. “The little Johnny Carsons go from birth to death, and the surfers are wiping out from left to right—“ he held up a weary hand to contradict me in some hard to read way, for I just waltzed right past his objections. “It reminds me of one summer when Dodie and I were teaching at Naropa,” I continued. “And right next door at the motel were Bernadette Mayer, and Phil Good.” Wayne shifted in his seat, perhaps having heard this story before? “Bernadette was teaching a one-week course at the Summer Writing Program, and it was all about synaesthesia, because she’s one of the few human beings in America who are naturally synaesthetic. To her, you taste something, you see it, or whatever. That’s why she’s so great,” I chattered on. “Oh, and so many other reasons of course, but can you imagine? Anyway on Monday the students were shown a seminar table in which tiny plates of different foods were laid—chocolate—pickles—oranges—and they ate these blindfolded then wrote poems about each taste! And day two, was all about color, so they weren’t allowed to eat anything, just to feast their eyes on bolts of red velvet, blue satin, white Arabian cotton, purple tweed!” “And write poems about it,” suggested Wayne. “Exactly, and I forget what they did on day three, but it must have been all about smell. Yes! There was a plate of pine needles—and a rotten egg—and a saucer of milk—and shavings from a rubber tire—and then they wrote poems about it! Sonnets! And gradually all these things combined in their heads into synaesthesia! And the last day the students were supposed to take acid and write more poems! It was the total immersion of the image, Wayne, like a mouthful of, I don’t know, color and light and—oh, I guess, reference too! Bernadette Mayer is awesome, but I guess everyone knows that, don’t they.” “I don’t know about everyone else,” he allowed, “but I think she’s great.” Chastened I made my way out of the garage and continued in the moonlight down to Market Street, a flood of moving engines going this way and that way.

overundersidewaysdown, Queen’s Nails Annex Gallery, March 31—April 29, 2006, 3191 Mission Street, San Francisco, CA 94110, (415) 706-1795,