I Did Not Pee on R. Kelly’s Soulacoaster

01.08.12

I just read all of R. Kelly’s memoir, Soulacoaster, in one sitting at home on Friday night in my boxers on my sofa. Soulacoster is 375 pages for $29.95, full color with image inserts of rose petals and rollercoasters and basketball textures featuring pull quotes from the text you read of the story of R. Kelly’s life. I feel conflicted because I feel like the book was written for people who are somehow both thirteen and in their late 40s at the same time, and I am neither of those. I feel like I’ve been washing cars all days in the hot sun while someone mumbled at me in a foreign language through a bullhorn and I was wearing short shorts and now I’m sunburned. That’s my fucking review of Soulacoaster at 1:28 a.m.

R. Kelly claims that at age nine he had a dream that his “biggest hit song” appeared at his front door in the form of a cloud of giggling cartoon music notes. He claims that it took him 20 years to remember what he played on the piano after that in the dream, and then that became the song “I Believe I Can Fly” for the movie Space Jam. I have four R. Kelly albums on my iPod right now that have been there for two years and I only have an iPod mini which means I can put like fifty albums on it at one time. That’s 8% R. Kelly. I don’t know what I was expecting when I bought this book. I knew no matter what the book said I would want it and I would probably sleep with it after I was done because the book is titled fucking Soulacoaster and the subtitle is The Story of Me. Listening to R. Kelly reminds me of getting killed by children carrying huge blue swimmy noodles with microphones attached to them that make bass notes out of how they muffle from beating against your flesh. By this I mean I love his music very much.

A lot of this book is either R. Kelly talking about fucking or God. God and fucking are the two main motivators of R. Kelly’s art besides his mother. He also likes to play basketball. His earliest memory of getting horny was at age eight, of being surrounded by “cousins, aunties, friends of my aunties” walking around his mother’s house stripped down in the heat and sweating through their clothes, often not wearing panties. He delivers the line of dialogue, “Uncle Doug, why you always wanna be looking at big titties?” pages before receiving his first blowjob, still a child. The way he mentions this extremely strange and obviously fucked up world of hypersexuality is as common as the way he talks about McDonald’s; he doesn’t seem to notice any difference; his manners of speech are almost always just slightly off. His first visual experience of sex was walking in on a scene where, “A man’s backside was high in the air, coming down on the lady with her legs spread wide open, her big booty propped up on a pillow.” That sentence is like cubism got raped by cartoons and smiles. I just added Soulacoaster to my word processor’s spell check function so it will know forever that is a word.

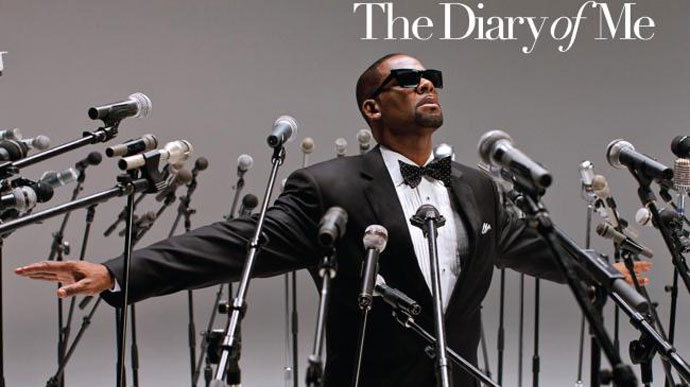

I don’t know, this book is fucking weird. It’s weird in a different way than you would even imagine the self-proclaimed king of R&B’s autobiography. It’s a mess of like at least eight different voices. Some sections seem like R. Kelly was actually dictating the language, and sometimes it’s ad copy or Wikipedia tidbits. He never seems to actually be able to talk about what goes on in his brain when it comes to music, as any time the book directs itself toward inspiration he comes out with lines like, “Because I absorbed music like a sponge absorbs water, I couldn’t help but soak up every thirst-quenching drop.” and “Sometimes I feel like music has made love to me. And sometimes I feel like music just had sex with me. I feel I am pregnant by music; and it is the father and mother of my child.” He explains how when he thought of the first lyrics that would become Trapped in the Closet it scared the shit out of him, but he doesn’t think any deeper into what that fear meant other than, “Like a cannon stuffed with cannonballs, my head was stuffed with songs.” Each chapter dedicated to a new album or performance in his career gets glossed over with hyperbolic descriptions of his work, complete with sales numbers and radio chart information. He’s both confident and self-consoling, saying shit like: “I didn’t mind singing a lyric like ‘I’m fucking you tonight’ in a club jam. I thought it fit into that slot perfectly, and so did millions of fans who bought the record.” As he moves further and further from the artist who wrote 12 Play and deeper into the guy who got famous for his pee, the more he seems to retreat into cartoon style, the willful plasticity. The last 50 pages of Soulacoaster are pretty much long explanations of his albums and why they are underappreciated, including pull quotes from press reviews praising on top of G-rated images of himself staring dead-on out at you as if to hypnotize your clothes off (ladies only). Somehow the whole thing feels at the same time hyper-sexual and neutered, a literary holographic scratch-n-sniff without the smell or the reflection.

But even then, littered among the jargon, snippets crop up that seem to reveal a lot about the man inside the man himself, such as his having proposed to his wife while climbing out of a “chopper” and shouting over the engines in what must have seemed like a Bruce Willis movie in his mind, followed by a full-page spread of his wedding vows written out in cursive. You get the idea that a lot of what feels like pap or copy-talk here is actually a part of the man himself: that what makes him so compelling as an artist is the mix of monolithic retardation and unblinking seriousness that seems to have no border between his music and his brain. His fantasies of having the Sears tower fall over on him and memories of a man named Mr. Blue who offered him $5 to “rub on his dick” and lines like how he spent “Seven years of living with the sharp edge of a guillotine repeatedly hovering over my jugular” due to the lawsuit all sit right alongside obvious distortions such as how the teacher on his first day of high school who he claims pointed at him on sight and declared, “You are going to be famous. You are going to write songs for Michael Jackson,” and perhaps damaged attempts at elucidating the origin of art: “Sometimes my gift is my enemy. My head is like an over-inflated balloon, filled with sounds that swell my brain to the extent that I fear it might explode. When it does explode, I find myself in a new and beautiful musical place.” It is the jumble of all these things together, which fail to synthesize or elicit anything that feels all real, that end up fumbling into something awesome to know exists in a way that transcends even needing to read it. Some objects you keep around more for what they represent than what they are. There’s something capital-B Beyond about R. Kelly, a thing we were never meant to know, and this document does not tell us, and so in its wake the world is safe, if somehow at the same time that much closer to destruction.

I’m not going to tell you this is a well-written book because you wouldn’t believe me if I did, and really I can’t imagine anybody would ever expect that of Soulacoaster. I will say though that the bizarre distortions and the gloss babble and absence of confession is unforgettable despite the way it seems to have turned my brain to mush. The whole thing seems accidentally honest the way a chat bot can be honest, or a window, or a man who believes his dick can make you see God. It’s an artifact of somewhere else. I’ll remember this book longer than probably most anything I read by anyone with an MFA in the last five years. R. Kelly is no John Updike, and bless his ass for that.