Homestead Beyond the Clouds: A Review of Kids of the Black Hole

24.10.17

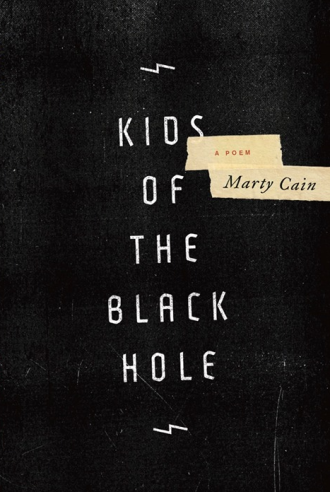

Kids of the Black Hole

Kids of the Black Hole

by Marty Cain

Trembling Pillow Press

67 pp / $16.00

I found a homestead beyond the clouds

between the headlights of youth & the infinite chasm

in the interlocking apartments of my mossy skull

I put my ear to the wall & heard the voices

I don’t know. Maybe Marty Cain is already dead and this book-length poem is a haunting—a sterling blue worm of a specter, wiggling, filmstrip-like, poking its head out from time to time, out from a rotting corpse, here to tell the tale of not another young visionary poet, but a re-visionary poet. A poet that makes a livable space out of trauma and suffering, even after being violently eaten down, fractured by the bleakness of the ‘burbs and untrustworthy adult lurkers and every last inky, predatory eye. Or maybe the unfolding of this poem is similar to whatever happens to the soil that surrounds a body mid-decomposition. Maybe it’s whatever the newly nutritious earth begins to resemble. More of some kind of mutilated sky—the kind with stars that flicker like maggots. With no regard to time or pacing. Like a wastefully blue movie of a poem:

this is my last poem

this is my poem like a festering wall

this poem the place where runaways stay

this poem comes from grass & is piss from the stars

this poem in the stairwell with buzzing fluorescents

this poem with the balcony over the plaza

how you close your eyes

I imagine you plummet

your body over seven stories staring down

your body testing the weight of inertia

the weight of the tethers that keep you blue

In The Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults, poet Joyelle McSweeney writes, “[…] my term ‘necropastoral’ is a reworking of classical notions of the separation of the rural and the urban, the idyllic and the worldly. Instead, I acknowledge that the most famous celebrity resident of Arcadia is Death; my necropastoral suggests that there is no wall between ‘nature’ and ‘man-made’ but only a membrane, that each element can bore through this membrane to spread its poisons, its Death to the other.” Perhaps Cain’s epic is a prime example of the sort of necropastoral that McSweeney has described. Perhaps it is a poem thoughtfully spreading its poisons (i.e. “this is my screw being yanked from decades of paint / this is my poisonous poem which lives in the lead”). The long, intricate after, the microbial livelihood that makes a necropastoral possible. Kids of the Black Hole feels like something we shouldn’t be allowed to read. There were times when I felt as if I couldn’t continue reading. It feels like a “homestead beyond the clouds.” It feels like something “shocked back to life.” I honestly haven’t felt this affected by a book—by a poem—in a very long time.

“House of the filthy, house not a home / House of destruction where the lurkers roamed / House that belonged to all the homeless kids.” Cain’s 2017 debut book shares a title with the 1981 track, “The Kids of the Black Hole” by punk band The Adolescents. Cain, beyond the existence of his poem, has also explicitly aligned himself with the notion of Arcadia many times. In a special 2015 installment of Tarpaulin Sky, Cain wrote, “My book-length poem Kids of the Black Hole is about what it means to be a teenage body in a rural space whose bones are constantly protruding, whose bones foreground the act of sweating and throbbing within a frame: the narrative frame, the gendered frame, the Arcadian frame, the frame of the Black Hole in southern Vermont where the mother fox roots through garbage to feed her young. My poem believes in the young.” His twitter profile currently reads “arcadian holiday.” And, most notably, Kids of the Black Hole begins with an epigraph from Shakespeare’s As You Like It:

“TOUCHSTONE: Ay, now am I in Arden”

-As You Like It, Act II, Scene IV

In reading the speaker of Cain’s poem as a deathly voice alongside famed clown and pastoral spoofer, Touchstone, there’s an obviousness to Cain’s desire to write outside of a traditional pastoral mode. One might recall when Rosalind exclaims, “Jove, Jove, this shepherd’s passion / Is much upon my fashion!” To which Touchstone replies, “And mine, but it grows something stale with me.” This exchange follows a description where Touchstone performs a parody of the pastoral condition, saying, “[…] I remember the kissing of her batlet, and the cow’s dugs that her pretty chopped hands had milked; I remember the wooing of the peascod instead of her.” The scene concludes with a line that possibly echoes McSweeney: “But all is mortal in nature, so is all nature in love mortal in folly” (2.4.40-60). Like Touchstone, Cain is attempting to expose the pastoral as an unnatural, inescapable hell. A place of damnation. For instance, Shakespeare acknowledges such inescapabilty in another passage by way of Touchstone:

That is another simple sin in you, to bring the ewes and the rams together and to offer to get your living by the copulation of cattle; to be bawd to a bellwether and to betray a she-be’st not damned for this, the devil himself will have no shepherds. I cannot see else how thou shouldst ’scape. (3.2.75-82)

We know Cain “believes in the young,” but perhaps Kids of the Black Hole is also a daring escape attempt. To combat the gorier moments of growing up, Cain chooses to cycle in and out of painfully difficult moments of teenaged wasteland. Cain’s speaker wants us to confront the violence imposed on youth, as opposed to being complicit with or ignorant to the everyday occurrences of such cruel violence. Perhaps we are dealing with a different kind of shepherd here. A speaker herding a variety of “blue” selves, all navigating different states of being—as well as different states of dying (“I dreamed I was facedown in some mud in the woods / I dreamed I was a cat floating dead in a brook / with a prophecy hidden in its glassy eye / I dreamed I met the devil on the side of the road”). To breathe life back into the blue and suffocated youths of a crumbling suburbia, Cain’s speaker’s lines repeat and thump loudly, heartbeat-like, sometimes laughing and sometimes crying. Sometimes living and sometimes dying. Sometimes at the same time. In the same void, confessing:

It’s easier inside, the face sang back

it sang in the half-hearted thump of iambs

it sang like the elderly making love

it sang to lambs surrounding your bed

This is the poem in which I dip my splintered feet

Anaphorically, the quick draw unfolding of Cain’s poetic narrative reminds me of the relentless, lyrical intensity of a 28-year-old Frank Stanford’s 15, 283-line epic poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. But the similarities between the two poets also go beyond syntax and poem-length. Like Stanford, Cain, too, is interested in both dreamscapes and stars. They share an appreciation for excess and a fascination with Death. Oddly enough, Cain is also a young poet who turns just 27 this January.

I know the exiled lover

I know there was one Inazo Nitoba who wrote about swords

I know the men dragging twelve foot of cotton sack

I know Hammurabi’s code was broken by lawyers by bunkam buy it

I know the teachers in the side show the paddles out of my way

I know the houses with the furniture like ghosts

I know the octopus in my dreams the messages of light I receive from the stars

the pioneer’s mirror

(Stanford 8)

Cain’s stars are sometimes repeating lines of asterisks. Typographical stars. Sometimes these peculiar stars are used to deliver coded messages or reveal certain letters of the alphabet. How do we read these stars? Forgotten words? Forgotten lines of poetry? Sometimes the stars appear to be concealing a poem not yet fully formed. Not yet finished. What is Cain alluding to? I note this, specifically, because at one point the stars mirror the syntax of one of Cain’s own poems. Are these stars, this sign activity, the feelings, the right words we search for in the face of death? Are these the words we struggle to string together to do one’s death justice? To remember someone once alive? Is this barrage of stars the Facebook status you never thought you would have to compose? Are these stars the poem that takes the longest to write? The un-writable poem? The elegy? The hole-like night?

************************

********************

***********************************

*************************

********************

*************************

********************

From the very first page (“he said I’m watching you, we shook him off / we went further down beneath the earth”) to much, much later (“is heaven a holding cell / is God a cop”), there’s a constant purgatorial and panoptic sensibility to the way in which Cain’s blue-bellied, blue-threaded, blue-veined bodies pace and repeat beneath a prison-like nighttime sky of stars. However, Cain also appears to be confessing that purification—restoration—isn’t a possibility in a society already in ruin. In the same vein of Leo Bersani, Cain doesn’t seem to necessarily believe poetry to be some sort of cure-all for social decay (hence its more poisonous attributes), but does still believe in the medium as an opportunity to address what’s always-already being internalized. What’s always-already haunting innocent, susceptible bodies.

In many ways, we never leave the trappings of the opening image of a “mossy skull.” This beginning, this honing in on death-and-life, again, aligns with the opening of Stanford’s The Battlefield, which begins with a Cadillac and a funeral. We nightcrawl from beginning to end, moving backwards, inwards, through old memories and into and against a gripping language of trauma and fate. At times, there are instances when the unfolding of language becomes extraordinarily measured, seismic, and, above all, filmic. I see so much of Godard in David Lynch’s Inland Empire (2006) and I see so much of Inland Empire in Kids of the Black Hole. Cain, his own meticulous storyboard artist, knowing precisely when he wants to pull back his camera to reveal the next clue, the next influence, the next brushed-aside victim. Always knowing what he plans to pan to next. In Cain’s surreal realm of dreams and sinister interiors, everything gradually becomes a process of peeling back or stripping away. Like a camera that keeps pulling back to reveal—yet another camera! Yet another experience of consumption. Yet another painful memory:

you switch on the brights & pupils dilate

I zoom into your wrinkles

I search for a focus

I blur for a second & then become clear

no one knows just what happened

no one knows why you veered left

or why you were swallowed in the traffic current

Cain’s choice to make the speaker perform camera-like actions (“blur,” “zoom,” “focus”) feels reminiscent of the metatheatrical qualities of Shakespeare’s As You Like It. Additionally, in regard to cover-ups and questions of real versus fake, hollow realities, psychological violence, and physical abuse, I also see flashes of Gregg Araki’s Mysterious Skin (2004) in Cain’s book—a similarly disturbingly blue-haunted narrative that follows the lives of two teenage survivors of childhood sexual abuse. The characters—Neil (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Brian (Brady Corbet)—struggle throughout the film to come to terms with an odd memory they both share. A memory of being abducted by a pulsingly blue U.F.O. “I think I was taken, too,” says Brian at one point. But, ultimately, the U.F.O. ends up being a stand-in memory for something else. A strangeness, an incongruity somewhere in their interiors, somewhere in the catacombs of the mind, concealing harrowing trauma. Cain writes:

I filled up pages & hoped to be taken

for this poem is my one abduction

for I know the transmission cometh from elsewhere

for I know a Martian in my soul

for I know the rain is not the rain

Blue-stained and beautifully obscene, Kids of the Black Hole is a chance to attempt to translate the graffitied alleyway walls of small-town America. Some of the imagery might shock you. Much of the content might unsettle you. But it’s important to let this gratuitous, starry-walled poem flood you. With its sleeping bags, with its blood trails. With its cowtipping boys, with its blindfolds. With its broken bottles, with its cracking knuckles. With its black holes. Let it flood you and exhaust you until you see the whole picture. Basquiat once said, “Every single line means something.”

I looked down the hole

the longer I stared the deeper it got

& the deeper it got like an eye beneath

the oracular mouth of moon above