Holy Man: Dennis Wilson Revived

30.07.08

Ever since his burial out in the Pacific Ocean’s coordinates of 33-53.9° N/118-38.8° W in the first week of 1984, Dennis Carl Wilson has remained silent. Drowned after Christmas in 1983, in those same waters that he dedicated his lone solo album to, Wilson wasn’t around to partake in the Beach Boys infamous appearance on Full House (and is therefore absolved from the sins of “Kokomo”) and also missed the reemergence of SMiLE, his big brother’s lost Beach Boys album, recast now as a Brian Wilson solo album, in 2004.

Ever since his burial out in the Pacific Ocean’s coordinates of 33-53.9° N/118-38.8° W in the first week of 1984, Dennis Carl Wilson has remained silent. Drowned after Christmas in 1983, in those same waters that he dedicated his lone solo album to, Wilson wasn’t around to partake in the Beach Boys infamous appearance on Full House (and is therefore absolved from the sins of “Kokomo”) and also missed the reemergence of SMiLE, his big brother’s lost Beach Boys album, recast now as a Brian Wilson solo album, in 2004.

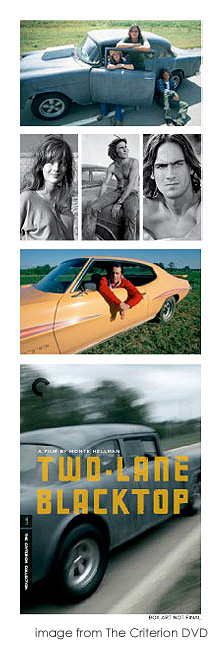

Perpetually in the shadow of that big brother, only now does Dennis Wilson get his own renaissance: since late 2007, Wilson’s meager body of work has reappeared to greater appreciation. The esteemed Criterion Collection filled two DVDs and a book with 1971’s massively hyped road movie flop from director Monte Hellman, Two-Lane Blacktop (the only film appearance of both a Beach Boy and “Sweet Baby James” Taylor). And then this spring Sony lovingly made a two-CD set out of Wilson’s long out-of-print solo album, 1977’s Pacific Ocean Blue, and the demos he never sobered up enough to finish, Bambu (named after the rolling papers). In keeping with the theme of singing drummers, the set concludes with the Foo Fighters’s drummer Taylor Hawkins (who plays for a band whose own frontman was once the drummer for a world famous band before stepping to the mic) belting out a dead-on, barnacle-throated Wilson impersonation on Bambu’s “Holy Man.”

“Holy Man” doubles as the sub-theme for the Wilson set, as it grapples with understanding the man and his maddening contradictions that were laid to tape. He gets fondly remembered as big-hearted and lovable, a natural (and naïf) on piano—an impression that comes courtesy of “the Captain” Daryl Dragon (of Tenille fame)—a man too sensitized to last long in this world. But if Wilson’s a holy man, then he’s of the Mr. Natural variant, with a prodigious sexual appetite that conquered such lays as President Regan’s daughter, Christine McVie of Fleetwood Mac, fellow Beach Boy Mike Love’s illegitimate teenage love child, and the clap-bearing ‘daughters’ of the Manson Family. He also had an appetite—for dope, vodka and orange juice, and other illicit chemicals—that may’ve not been on the same level as his big brother’s—but which was nevertheless frightening to those around him.

Contradictions and conundrums abound, not just in Wilson the person, but in his art. Wilson was the only Beach Boy who could surf and the only actor on the Two Lane set to know his way around an engine (and yet in a movie starring two bona fide pop stars, it’s only tin-eared co-star Laurie Bird who actually sings). Wilson’s the guy who could turn his band-mates onto Transcendental Meditation and then nail groupies in the band’s meditation room. Who else but Wilson could make wholesome the act of the Beach Boys stealing a Charles Manson song (retitling “Cease to Exist” as “Never Learn Not to Love” off of 20/20)? For every astonishing chord progression he flashes on POB, there’s an insipid rhyme scheme to bury it. As he laments pollution of our rivers and oceans, he’s similarly hellbent on destroying his own body.

As both TLB and POB trot out their glossy remembrances of the deeply troubled man, odd things get said. POB producer James Guerico notes that during recording, “Dennis was the most present person I’ve ever known.” Which is a slight deviation from director Monte Hellman’s observation that:

I don’t think I’ve ever worked with an actor who was so unself-conscious. He had no awareness of the fact that there was a camera. Or even that he was acting in a movie. He got so involved in what was going on, not as a character but just as an observer with these other people. He really related to everybody in a completely realistic way. It was the perfect definition of what acting should be. He believed everything that was happening.

Two-Lane Blacktop itself is paradoxical, both aware and oblivious. As Kent Jones notes in an essay accompanying Criterion’s DVD, it’s “a movie about loneliness, and the attempts made by people to connect with one another and maintain their solitude at the same time––an impossible task, an elusive dream.” Cooped up in a car, Hellman’s camera also shoots via wide-lens the expanse of Route 66. From the flicker and whirr of the projector over the opening title to the final frame melting in the gate that ends the ride 103 minutes later, Two-Lane Blacktop is a B-movie about racing that’s cognizant that it’s a movie about racing. Which means that it can therefore wholly embrace the subject of racing, while chucking plot and meaningful dialogue. It’s a movie as streamlined and trimmed of excess weight as the ’55 Chevy (lightened by fiberglass windows and an unpainted aluminum shell) itself.

The film also features Warren Oates’s most heart-breaking and uncanny character (which is really saying something), G.T.O.—that dashing, sweatered bullshit artist and friend to hitchhikers everywhere––who grows more and more inscrutable and mysterious with each subsequent viewing of the film. That Wilson’s Mechanic matches up enigmatically onscreen with Oates speaks volumes about his own gravity, playing (or rather not playing) his part perfectly. Thumbing through the original screenplay from Rudy Wurlitzer (also included in the DVD set), the stage directions for The Mechanic are as follows:

his expression passive and unchanging

and

his expression remains passive and cool

which Wilson pulls off, all the while keeping his star core smoldering: the lone memory Melissa Hellman (Monte’s young daughter) has from that time is how great Dennis’s butt looked on set. And who else could answer a line of dialogue like “You aren’t the Zodiac Killers or anything like that are you?” with “Just passing through!” and have it make more sense?

While handsomely chiseled as he mugs for the camera in Two Lane Blacktop, barely six years on, Wilson is weathered, bearded and brined in alcohol on the cover of his album. The first solo release by a Beach Boy was a modest success, selling some 300,000 copies at the time, somewhat overshadowing the band’s own Love You, itself a vehicle for the purported return of his brother, Brian.

While handsomely chiseled as he mugs for the camera in Two Lane Blacktop, barely six years on, Wilson is weathered, bearded and brined in alcohol on the cover of his album. The first solo release by a Beach Boy was a modest success, selling some 300,000 copies at the time, somewhat overshadowing the band’s own Love You, itself a vehicle for the purported return of his brother, Brian.

Over thirty years on, POB has aged rather well. Though at times it could sound like a Glenn Fry solo album (and might make us re-appraise such a beast) with its mix of machismo and gruff-earnestness, its AOR (album/adult-oriented rock) is just skewed enough so as to sound like a Wilco album, too. Drummer Wilson dabbles in almost everything: Steinway grand, Rhodes, Hohner clavinet, Moog, Hammond. Again, contradictory notions course through it. There’s the deluge of gospel in the opening of “River Song,” with its startling chord progressions that elevate it far above its own dreck rhymes of “city/ pretty.” Elsewhere, Wilson—already a huge star—sings about wanting to be a movie star on “Dreamer” and a rock star on “Under the Moonlight.” (The former recalls a story his friend Chris Clark told Steven Gaines in his book, Heroes & Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. Near the end of Wilson’s life, Clark snapped at him one day: “You know, your problem is that you’re just mad you never made it as an actor. That’s why you have to act everything out.” At this accusation, Wilson perks up: “How did you know that?”)

Two particular tracks showcase both extremes of Wilson’s art and persona. On the unfinished sketch “I Love You,” we get the lizard mind at its most plainspoken, with Wilson basically singing about busting a nut (“I’ve waited so long to let my love flow and now it’s alright”) before a choral approximation of a post-coital male afterglow washes over us, all ahhhhs and aural bliss. From the plaintive piano emoting on “Thoughts of You,” Wilson hints at a minor key melody not dissimilar from “Theme from M.A.S.H.” before swiftly descending into a middle section that is honestly one of the most devastating things I’ve ever come across in an AOR song. There’s a vocal arrangement quite unlike anything the Beach Boys ever attempted, with Wilson’s multi-tracked voices intoning the observation that “all things that live one day must die, you know/ even love and the things we hold close.” “Even love” repeats again and again, Wilson anguished at the realization, voicing the unplumbed depths of a heart being carved out. Soon, we get thrown back to shore, to the slight twinkling piano of the beginning, but we remain shaken.

Surface shimmer and/or oceanic depth, it remains impossible to parse Dennis Wilson as either a drummer, a B-movie actor, or anything loftier. Holy man, wholly present, a man unconscious of the film he acted in, voicing his most primal urges and his most enlightened observations on life, staring deep into TLB or listening close to POB, no answers shake out. Contradictory or no, Wilson himself plowed straight ahead. Or as he sings on the unreleased Beach Boys’ song “San Miguel”: “I go where I’m going/ Goin’ straight ahead.” Which meant both the lateral and eastern nihilism of Two-Lane Blacktop (which never reaches the East coast) and the silty bottom of Marina Del Ray that ultimately leads us out into the Pacific Ocean’s blue.