Here’s When You Fall In Love Again: An Interview with Rich Smith

30.09.14

Rich Smith’s All Talk, his first full-length poetry collection, arrived from Poor Claudia August 1st. It’s a book with lines spread over highways, unmanicured beaches, porch-sits, Internet shopping, “that guy”s, “healthy women… in twenty-dollars worth of clothes” and “hometown knockouts”. So it’s appropriate that I meet him at a bar called the Neighbor Lady in Seattle. And appropriate that just after I greet him he has to step out to take a phone call. And that while he is outside, somehow Sugar Ray’s 2001 single “When It’s Over” comes on (a song that really is unexpected in a city that prides itself on its musical taste), with its chorus that begins “All the things that I used to say,” my soundtrack while I sit in the bar and watch, out the window, Rich Smith talking on his phone. Smith’s poems are like that, too, their everyday topicality immediately announcing a deeper resonance, their casual tone floating over expert craft.

At the Neighbor Lady, we drank beer, ate fries, and talked about his book.

FANZINE: There are a lot of places I recognized in the poems from the Midwest and Seattle and I was wondering how remembered those landscapes are. There are a few references to traveling from place to place—“I Can Fit Everything I Own into A Camry,” for example—and I wondered how important it was to you to be from one place and writing about another place, and I know you’re about to move again.

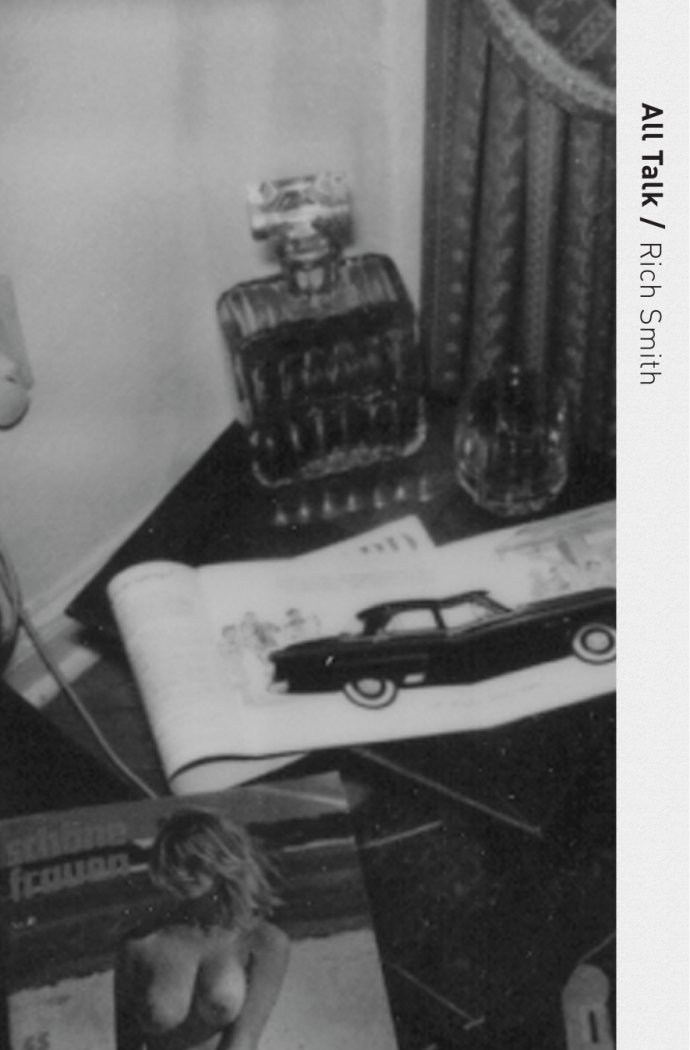

RICH SMITH: I’ve been in school since 2004, when I went to school in Missouri, and then I moved to Ohio for grad school, and then I moved out here to Seattle for grad school, so it’s been a kind of really responsible bumming around, I guess. And I did have that dream to kind of travel around America when I was young. I wanted to see all the country. I was landlocked and I always wanted to have a more cosmopolitan life, or one more based in the city, and so I traveled a lot of long distances and a lot of the poems are about that and some of them are remembered but I also used a lot of photos, too. My friend David Zubeck, actually, who did the photo on the cover of the book, he took all these photos of the Midwest and sent me all these photos during my second year in Seattle and I realized that place was more formative than I thought. So I started writing poems about memory and the hometown off of those photos, using the ekphrastic stuff to get the juices flowing and then the memory to fold in the details. The form that a lot of those poems take is anaphora or anaphoristic. And those forms are tied very closely with memory, the refrain and anaphora. So it made sense to be remembering and be using those forms.

The ultimate truth of that traveling is that there are great, vast differences from place to place, but mostly the happinesses are the same and the happinesses for me are always located in people, food and drink. Like these waffle fries.

FZ: I heard there’s boobs on the cover.

FZ: So if remembering leads to lyric forms, what are the emotional states behind the other forms?

RS: There’s this longer poem called “Glut” in the middle of the collection. I think of it as a “reverse erasure” or something. It starts with a small spine and instead of taking away and erasing words and using that as a kind of a series I thought to do the opposite and to add lines and to morph words within the lines of each new poem. And that form matched the content of the piece to me because that poem is about excess, all the memories that we have—there’s way too many memories and they’re basically useless—but also just consumerism, big data, just the whole big mess of stuff. Poetry is a whole great art of condensation and I was wondering if I can get at that idea of glut in a formal way.

FZ: Do you think that particular poem is anti-poetic or meta-poetic in a way? Because if poetry is condensation and that poem keeps getting bigger then…

RS: I think it’s not anti-poetic because it gets bigger based on rules. My favorite part of writing poems is discovering a logic and seeing that logic evolve from the beginning to the end. The drama of that logic, the drama of the unfolding of that logic, is one of poetry’s chief pleasures. So just because it’s expanding doesn’t mean it’s not also contracting, that it isn’t a condensation of experience. Anaphora’s that same way in that it’s the same line and you’re adding and adding and adding.

FZ: I’ve known you for a while now.

RS: It’s true.

FZ:It’s true. I’m going to write in the smile we just shared. I don’t really think you’d write any kind of anti-poetic statement or anything that was like, “What is this poem for?” That’s just not a sentiment I’ve seen from you, a kind of doubting the “power of poetry” or art or the life of being an artist. But what kind of mistress has poetry been to you? Where did it begin? How is it going? You and poetry: what’s the scoop? You’ve been together awhile.

RS: We’ve been together a while. Man, I’ll tell you. That is a really good question to ask right now. There’s so much I could say.

FZ:Say it all!

RS: Right now I don’t know. It’s such a compulsion at this point. It’s just so woven into my daily practices, the writing and the reading. Rick Kenney, my thesis adviser at UW [University of Washington] said something that I say to my students which is basically “The syllabus is the syllabus for life: reading, writing and conversation.” I feel like that’s all I do. I don’t just do it with poetry. Recently I’ve been getting into screenwriting and journalism and corporate writing and a lot of different sorts of writings and I’m learning from all of those different modes and how they all inform each other but poetry specifically is the one. It’s the one true love. And like all true loves it fades and redoubles in significance. You’re in a relationship with someone and it’s the same way. There’s a line in the book “the day I remember you kissing me is the day I’m so tired of you kissing me.” So sometimes I feel that about poetry, but sometimes I pick up a poem of Walt Whitman’s and I’ll be moved to tears and suddenly think it’s all possible again. I just read something in Pinwheel by Emily Toder and was like [sound a lot like Howard Dean’s 2004 race-crushing “Dean Scream”]. Poetry!

But how it all began. Two things. I totally fell in love with my beginning poetry professor, so a lot of this has been trying to quietly impress her, since I first saw her. And then this Frost poem that I fell in love with called “Spring Pools.” That was the first moment when I first had the feeling of seeing the machine of poetry, seeing a rhetorical poetry move enact the thematic concern of poem. In the poem “Spring Pools” Frost says “These pools that, though in forests, still reflect / The total sky almost without defect, / And like the flowers beside them, chill and shiver, / Will like the flowers beside them soon be gone” and in that last couplet the lines reflect each other almost without total defect like he claimed the spring pools reflect the sky almost without defect. And when I saw that I was surrounded by white light and my vision blurred. I mean I was skeptical of epiphanic moments and maybe I was a little high but I remember feeling very pleased by that machine and wanting very much to find more of those machines and to see if I couldn’t build them myself.

FZ: I don’t want this question to misconstrue the tone of your work, but there’s this one big word. Here, I’m just going to show you.

RS: Borborygomous! It was the word of the day in my dictionary.com app. It means a great bubbling up. Actually it was Thanksgiving and Willie [Fitzgerald] was frying the turkeys and I looked down at the app because I got a little bored watching the turkeys fry and I saw the word “borborygomous” and it meant “a bubbling sound” and I was like “the turkey is making a borborygomous sound!” And there’s something in that poem, “The King of the Babies,” about the dead speaking up. There’s a trope in poetry of the dead speaking and the poet carries on the voice of the dead in some way. The metaphor that’s always being used is that of birds. Poets are compared to birds a lot because a bird is born with a song, so the robin now is singing the song of the robin 10,000 years ago. And that kind of miracle or relationship to song is often related to poets singing the same song in some way as Whitman or Chaucer. Same birds. I sort of write in a chatty lyric kind of mode. Some people think that style is limited and I hope the book shows the range of that talky style which I inherit from O’Hara and my teachers. The book is really just me doing my best impression of Heather McHugh, Mark Halliday, Frank O’Hara and Emily Dickinson, and Mary Ruefle.

FZ: So showing the range of the “chatty lyric” was an aim of this book. What about future books?

RS: Other than the other forms of writing I’m doing—essays, movies…. I’m going to keep writing poems forever. I hope I write books that the form of the book will make sense with the content of the poems. I don’t think I’ll ever get a wild hair to write about some slaughter in Missouri in the Civil War from the perspective of a ghost. I walk around and I often start out with a line or a riff and that’s how a book starts, too. You start with a small poem and see how they expand out together. I don’t really have any aims other than to write poems that seem relevant and interesting and modern. And, yeah, I’m going to keep writing poems forever.

——————–

All Talk by Rich Smith is now available from Poor Claudia.

Tara Atkinson is a writer and one of the founders of APRIL, a festival of literature from small and independent presses.