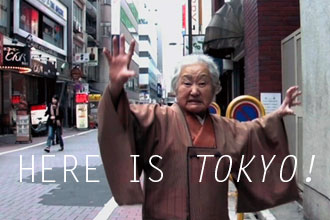

Here Is Tokyo!

06.03.09

Tokyo is obviously on the shortlist for our Sphere’s Most Photogenic & Glamorous City—for argument’s sake, let’s peg it 3rd behind New York and Paris. As such, it’s been the neon-lit subject for a legion of cinematic odes—some wish it smashed (see: Godzilla and Toho’s litany of lethal kaiju), others seize upon its yakuza cool (see: Seijun Suzuki’s New Wave films like Tokyo Drifter or Branded to Kill), but the majority simply delight in the city’s dazzling, frenetic appeal. Meanwhile, American productions like Lost in Translation and the godawful Fast and Furious 3 capitalize on its alien, ad-dense enchantment.

Tokyo is obviously on the shortlist for our Sphere’s Most Photogenic & Glamorous City—for argument’s sake, let’s peg it 3rd behind New York and Paris. As such, it’s been the neon-lit subject for a legion of cinematic odes—some wish it smashed (see: Godzilla and Toho’s litany of lethal kaiju), others seize upon its yakuza cool (see: Seijun Suzuki’s New Wave films like Tokyo Drifter or Branded to Kill), but the majority simply delight in the city’s dazzling, frenetic appeal. Meanwhile, American productions like Lost in Translation and the godawful Fast and Furious 3 capitalize on its alien, ad-dense enchantment.

Tokyo! is the hypermodern city’s latest portrait—a triptych, in fact. Co-opting the concept from other city-centered anthologies (Paris Je T’aime, New York, I Love You, and New York Stories spring to mind), it corrals three foreign writer-directors—two Frenchmen (Michel Gondry and Leos Carax) and a Korean (Bong Joon-Ho, who helmed The Host)—for their unusual, outsider take on Tokyo life. The metropolis, with its cosmopolitan and consumerist bustle, becomes a Rorschach test for each director: three starkly different fictions materialize (and to various success at that).

1: Anonymity

1: Anonymity

Based on Gabrielle Bell’s Cecil and Jordan in New York comic, the cleverly-titled “Interior Design” features Gondry’s patented adolescent-adults; in this case, go-with-the-flow Hiroko (Ayako Fujitani) and her would-be-Kurosawa beau, Akira (Ryo Kase). The two also happen to be the archetypical, hopeful, just-arrived couple that struggles to make an inch of headway in the big, soul-usurping city. As he awaits the debut of his hilariously incongruous sci-fi film, Akira ambitiously labors as a boutique gift-wrapper (you get the sense that he’s Gondry’s japonais-version of Stéphane Miroux, with the same insistent need to frame the real through reel imagination and the habit of parrying serious issues with charming asides); Hiroko, on the flipside, flounders in her search for viable lodging and employment, the pressure compounded by the fact that Hiroko’s friend houses the two at her fit-for-one apartment. Once Akira’s fantastical film screens to polite, halfhearted applause, though, Hiroko’s aimless lifestyle undergoes an absurd, Kafkaesque transmutation: her feelings have manifested themselves in a strange new way. With this, Gondry characteristically skirts the bleak reality with whimsical fantasy, yet he’s still able to beautifully—if bizarrely—capture the arbitrary value of human utility in any megacity’s crippling anonymity. Gondry appropriately frames the couple as the space cadets that they role-play, shuffled across Tokyo’s sprawl without any sense of assimilation.

Even in Japanese, Gondry’s dialogue lacks the twang of real-life. Its wearying effect is intermittently mitigated with wry phrases like “I’ve seen smoke inside a film, but never outside!” which a spectator enthuses about Akira’s ingenious debut gimmick of a smoke machine. But the visual presentation is typically majestic, from the initial shots of Tokyo glowing through a rain-smudged window to a variegated sea of towed vehicles; Gondry, who previously captured the city’s unearthly pace and person-abuts-person mash in a feverish Polaroid commercial, again justifies his numinous esteem by translating Tokyo’s suffocating claustrophobia and its overwhelming scale with relative ease—even if his narrative accents are slightly off.

2: Anger

2: Anger

Leos Carax’s transgressive, satirical segment “Merde” (“shit” in French) chronicles the sudden appearance of a racist, subterranean monster-man (Denis Lavant channeling his raving man-symbol from Jonathan Glazer’s seminal music video, “Rabbit in Your Headlights”) on Tokyo’s pedestrian-packed streets. After initially jostling citizens and stealing their cigarettes or crutches, the self-christened Merde soon escalates his anti-Japanese sentiment to indiscriminate mass murder (in previous Carax films this would be the protagonist’s descent into his amour fou), using a cache of hand grenades that he unearths alongside a rusted tank and a sign reading “Nanking 1937.” Coupled with Merde’s grotesque appearance (the media hones in on “his insane beard, his milky eye”), the discovery poses Carax’ thorny rhetorical question: what does Japan keep beneath its cleansed, twenty-first-century surface?

Maître Voland (Jean-François Balmer), a Parisian lawyer and a dead ringer for the Rasputin-like Merde, arrives to defend the new cultural phenomenon as he somehow speaks the same mumbo-jumbo language of squeals and guttural sounds. A trial ensues with the attendant media mayhem—Merde becomes an either-or symbol, both victim of and virus on the system, the regenerating newsfeeds forming what Carax calls his “smile of speed.” The director, in his first film since 1999’s Pola X, remains as heady and provocative as ever, but his new-baroque monster send-up—even with its great gallows humor and incendiary commentary on xenophobia and Japanese mass marketing—becomes somewhat exasperating. Like the more-is-less wisdom behind a fad like the Geico cavemen, the sentiment arises from the overuse of Merde’s point-making (read: judgment has already been passed on appearance) idiom—one can only handle so much of his harhar blather before it turns blasé.

3: Agoraphobia

The omnibus’ most elegant, stage-managed chapter, Bong Joon-ho’s “Shaking Tokyo” exhibits the delicate precision of an origami figurine. In this allegorical tale on urban loneliness and love, Bong introduces the term hikikomori, or someone who has shunned society. A terrific Teruyuki Kagawa plays the unnamed recluse who hasn’t left his home—and its homogenized patterns—for over a decade. In its confines, he’s overcome the entropy of the city with neurotically neat stacks of read tomes, toilet paper, and take-out pizza boxes. All his necessities are a dial away; when a delivery person does come, he makes a point to avoid eye contact and even touch. These initial scenes of isolation are typical but beautifully composed—cinematographer Jun Fukumoto’s camera drifts through the shut-in’s well-worn space, sumptuously enlarging and lingering on the trivial a few seconds at a time, miring the spectator in the middle-aged man’s droll, rinse-and-repeat life.

Then one fine day, a delivery girl faints during a serendipitous earthquake. It takes this literal groundswell to galvanize the hermit’s long-dormant emotions—he’s struck by that proverbial lightning bolt. This is also the moment of Bong’s chief misfire, in which he decides to emblazon the girl with daft tattoos (buttons reading sadness, hysteria, and coma, which the hikikomori pushes to wake her). To a degree, he redeems the corny motif by treating the hermit’s shocked-and-awed response to physical human contact with the tenderness of a first kiss—a grace he again exhibits when Kagawa decides to free himself from the self-cast cement in order to find this girdled angel on the outside. That’s when Bong magnificently turns the storytelling screw another 180 degrees. Though the closing shot spells bathos rather than the desired pathos, Bong’s surprising, melancholic, unresolved take on Tokyo still catches you wanting to extend your cinematic stay in this brave, new world.