Getting Back To Your Own Hand: An Interview With Ann Hamilton

04.10.16

For years, the old buildings on the piers of Philadelphia have loomed on Columbus Boulevard like ancient, rotting cakes standing between the city and the Delaware River. The pier buildings have giant archways, lacy molding, paint peeling, ports to another time that are weathering away.

Now, one of the pier buildings has been reimagined by Ann Hamilton in celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Philadelphia Fabric Workshop and Museum.

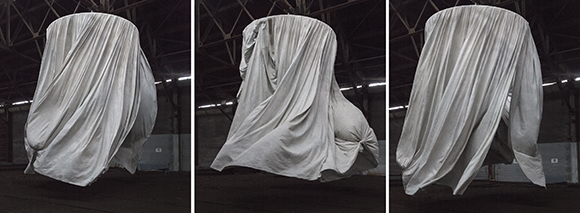

Stepping into Municipal Pier 9 feels like entering a surreal, open-air theater. Gigantic curtains dyed the color of the atmosphere are attached to pulleys. Cathedral-style ropes hang beside each curtain, and when you pull them just right, perhaps an accordion lets out a low moan. Then curtains begin to spin. The fabric takes life, the curtains reaching out tendril-like to brush your arm, then billowing like a fat clouds before subsiding.

Beyond the curtains, a man and a woman sit at a table, putting holes into a sweater as a poem by Susan Stewart flicks by on an old shipping container. Take a step past that, and a woman sits singularly on a stool, turning wool into thread using a drop spindle.

As with all things Hamilton, the exhibit is a many-layered event – the narrative of the curtains, the spinning poetry, the winding of the thread. And there’s so much more than that – a newspaper written by Hamilton traces the word sources of the work like veins, exploring whirling dervishes, the symmetry of the body, and the use of the piers. An adjacent installation at the FWM offers sample books, textiles, and commonplace textbooks.

Speaking with Hamilton feels like having a conversation with the sea. She is luminous, resplendent in a blue dress, blue eyes, the silver crest of her hair.

We sat on a bench before habitus, the river rushing by, the curtains spinning, to discuss creating dual installations, her process, and the years it takes to get back to your own hand.

Photo credit: Ann Hamilton Studio

SARAH ROSE ETTER: Sorry I don’t have any fancy recording equipment. Your last interview had that big microphone!

ANN HAMILTON: Oh, it was for a podcast. I’m a podcast fanatic.

Really? What are your favorites?

Ah, I love Radiolab, like everybody. The Moth. I like Krista Tippet’s podcast, On Being.

Do you listen to podcasts while you work?

No, I work in silence. I’m often writing and thinking in silence. And sitting here, looking at this installation now, I’m just learning the piece myself.

How do you mean?

Well, these things are so full of intentions. You’re dealing with engineering. You’re thinking about all of the relations. But it is not until it has gone up over these past few days, and being able to physically be in it that I can begin to feel what it is. Then I start to get new layers from it, too.

Every time you look at a work or talk about a work or write about it, you pull through a new thread.

For me, I’m really thinking about a landscape here. It’s also about a sociability. There’s a politic in here. There’s a demonstration of acts of making and unmaking in the face of this field of distraction. This is the immediacy. It’s about all the relationships between the parts. That’s what I’m always thinking about.

It’s interesting you’re finding new layers in it today. All of your work feels so complete and fully realized to me. It’s so associative. How does an idea start for you and how do you know when it is ready?

I think we all carry the baggage of what we’re interested in, and the sensibility through which we respond to where we find ourselves. You always feel like you are starting from nothing. Then the work is finished, and you feel like “Oh, it’s this again!”

Back to the same shit!

Yes, I thought I was doing something different. But here it is again!

But here, it was really responding to the history of the Fabric Workshop for the fortieth anniversary, and its’ history of textile-related processes. And that’s really the core of my own work. Even though I don’t literally sew and weave in the work, these are all woven relations. My thinking comes from that very early training with textile processes.

Photo credit: Ann Hamilton Studio

I’ve heard you speak before about listening to a space before coming up with an installation. How did you feel when you listened to Pier 9? How did it become this?

This project started a little differently from others. We have two exhibitions going – this one at Pier 9, and then we’ll be opening another installation at the Fabric Workshop. But we hadn’t found an off-site location yet, even though it was part of the original proposal. So a friend who had worked with the Philadelphia Opera Company told me to look at Pier 9. That led to this.

So this piece, in some ways, didn’t immediately form from responding to the space the way other projects have. We were already walking down this path of wanting to make spinning curtains, which takes an early vocabulary of mine and brings it into a landscape feel.

But often, you walk a space and you are very blank. You’re smelling and sniffing and trying to sense what the space is, what it needs, what it is asking for. You do it through the lens of your own sensibility.

Like your own gut instinct. That thing that can’t be taught.

You have to really just pay attention to what comes up. It’s all about that attention.

In this installation, the curtain fabric is dyed the color of the atmosphere. So each individual piece of the installation feels distinct but also the same. Can you talk a bit about that choice and process?

Exactly – just like people, right? I was thinking about the landscape here, obviously.

But this is like turbulence. This is the collaboration between a human action that is mechanical and rational, but that action is often eclipsed by weather and nature.

At first, I was looking at Hudson River School landscape paintings and I was really inspired by those. So the first curtains we made were very pictorial. But I stepped back to look at them, and I thought, “My god, this is really bad.” The piece had to become a landscape, not just display one.

So we redid them. An incredible team at the Workshop stained the fabric very lightly by tea dying it. So each one became a little different. Now, a lot of people say, “Oh, did you do anything to these?” But there’s a craft to being subtle.

They turned out really beautifully. And this installation also contains a full-fledged newspaper that you wrote. I just read all of the pieces and I wanted to talk to you a bit about language. The writing was very beautiful and precise, especially when you talk about the body, and the heart as a non-symmetrical object. When did you write these pieces? How were they created in conjunction with the installation?

I’d had this idea that I wanted to give a newspaper away during this installation. I wanted to write something that gave the reader a landscape of association that they could use to think about the installation.

And I had a residency in June at the Rockafeller Center. I was there with two other artists – one was Matthew Goulish, who is an incredible writer and actor. The other was Lin Hixon, a performer. They are both based out of Chicago. They really encouraged me during the writing of the newspaper.

But before this, I’d never sat down and actually taken that process seriously. It was really Matthew who was so encouraging. He said: It is so important for artists to write. He was very disciplined. I kept saying, “This is too hard!”

Language is difficult. It feels almost impossible to be precise sometimes, especially when describing your own work.

Language can be so generalized, and vague, and not particular. But it was really the encouragement of these other two artists I was working with that helped me to that. Then when I got back, I worked with a wonderful editor. She helped me really shape it.

I always envy visual artists. There seems to be such an ease to it. I feel exuberance in this exhibition, a lightness. I don’t feel that exuberance when I write.

Well, that’s because that’s what you do! But I think writing is much harder than what I do. Not that I haven’t worked hard on this, but it’s a different process. It’s just a different practice.

So let’s talk about this as a dual exhibition. What’s happening at the Fabric Workshop? I know you’ve selected some pieces from various museums.

So while the [Pier 9] installation has more of a landscape and a feeling of wholeness, what’s at the Workshop is more fragments. It is sample books, dye sample books, needle kits, a few of my things are mixed in with the historic objects. There are also commonplace books.

Yes, I know those are an important part of this. Can you talk about those a little?

In addition to text and textiles, I’ve been interested in commonplace as a practice and physical thing. In a commonplace book, you’re excerpting what you’re reading and setting it aside. I felt like the entries in a commonplace book were very much fragmented, and very much analogous to the fabric sample book. They are little pieces that touch you, and they are full of possibility. But they’re not the full thing. They’re not the full text. They’re not a whole.

Did you get to dig through a lot of cool stuff to find all of the pieces you selected?

Yes! We had this amazing tour through the textile curator at the DuPont collection. We couldn’t borrow everything, but we kept going back. We borrowed almost twenty or thirty blankets from them, and those blankets form a horizon line across an upper wall. Beneath that are wooden shelves filled with the commonplace pages that people have been submitting online. Those are also being given away. And in the cases, along with the textile artifacts, are commonplace books from the Rosenbach Museum and the Philadelphia Free Library. They just all have the hand.

There are so many pieces to both of these exhibits. You’re sort of like an octopus in that way, making all of these parts working in concert – the installation, the newspapers, the Fabric Workshop exhibition.

And I’m weaving them together. That is what I do. I was doing a short presentation on Friday, and I spoke about something that I don’t think I’d ever said in public.

Back when I was applying to graduate school, I was living in Montreal. I came down on the train to interview at the Yale graduate program in sculpture. During the interview, I remember being asked, “You don’t do this weaving stuff anymore, do you?”

And feeling…you know, textiles are associated with a lot of different places. They are associated with the female body, and I think there’s a rejection of the body in general. And I think I was very meek at the time. I don’t know what I said. I think I just didn’t say anything.

But it sticks with you.

It stuck with me — this idea of not trusting your own hand. Then comes this idea that it takes you your whole life to get back to your own hand.

So what I said in this talk was, “I’m always weaving. That is actually what I do!” Because everything is about relationships — and that’s what a cloth is. It is described as an event of two threads. And why would that be lesser than molding?

Or chiseling away at rock, or any other physical manifestation…

Yes. There’s a way that you develop a practice. That practice has a value in it, an ethos in it, and a social import.

There’s one thing jumping out to me right now. You and another artist from Philadelphia, Judith Schaechter…

Oh! She was just here yesterday! I love her!

Ah, I do too! And both of you sort of reject the title of artist. She calls herself a craftswoman, and you have referred to yourself as a maker. I find it really interesting – two women making powerful work, and pushing back against this idea of being artists.

I mean, if someone asks me on the plane, “What do you do?” that’s when I will say I’m an artist. Or I say I’m a teacher, because it’s a less complicated response. But I think I’m interested in that big sphere of what making is in the culture. So that word, which is a verb, the idea being “to make” – that feels more appropriate because it is active.

Where artist could feel passive?

Or it could feel other than. People don’t associate with the word artist the same way they associate with you if you say you’re a lawyer. But more than that, I make things. It just feels more appropriate to call myself a maker. I live in Ohio. I don’t live in New York. It’s about making permission for other artists to do what they need to do. You want to be part of making that.

You talk frequently about the silence of needing to create. Not wearing headphones and not wearing sunglasses. Meanwhile, the world is increasingly digital — everyone on their screens, that kind of thing. But here’s this idea of being remote to create.

You know, you aren’t remote no matter where you are. I’m just as hectic and busy as everyone else. I just don’t have as many voices coming at me. Someone once said to me, “The great thing about Ohio is that you can be as boring as you really are.”

But I think it’s more that maybe there’s a chance to listen to yourself a little bit more. And Susan Stewart, the poet whose work is included in this piece, said to me a number of years ago, “Your work is very smart. The nose of your work knows where to go, even when you don’t.” And you have to follow that.

There’s a bit of narrative in this installation too, talking about following that nose. We walk into a big space with the big spinning curtains. Then we move into Susan’s poems flashing on a screen as holes are being put into sweaters. Then we move into the final area, where thread is being created. Can you talk a bit about this? How did this structure come to you?

So first, we made the poem, and that’s what is on the cover of the paper. And then there was this process of reeling and spinning. That last piece of the exhibit is so important. A drop spindle is the oldest way to form thread, whether it is animal or vegetable. First it’s just existing, then it is plied and spun. And so you have the holes being made in the sweater, which to me feels like where we are right now. Then you have the creation of the thread.

In the end, the threads from all of these different sweaters are going to be tied end to end. And I think after that, I’m going to have them knit into another sweater. This installation is very interested in the capacity to make and remake, as well as the circumstance we find ourselves in.

It’s also telling a really nice story here, because you kind of find the thread at its first form by the end. I was also really glad you included the pulleys here as a reference to the ships.

And these are bell-ringing ropes that work the pulleys. And what’s interesting is the ropes are not as intuitive as I thought they would be for people. But the ropes are actually about letting go. So I put a quote up on the wall yesterday, which is a beautiful quote from this new book by Darren Leider. And he talks about how our hands are made to grasp and hold on, and how a child has to learn how to let go.

It’s interesting to see some folks pulling the ropes very quickly, while other people are more gentle.

Exactly. And I think that’s a lot of what the installation is about: This idea of practicing letting go.

Photo credit: Ann Hamilton Studio