Five Hundred Eighty-Six Days, Fourteen Hours, Forty-Six Minutes, Eleven Seconds

05.09.08

There’s a function reviled by nearly all Final Fantasy XI players, tucked among 24 others on the main screen menu: one small, innocuous-looking icon that reads “Play Time”; a button that seems to hold all the dark secrets of that particular player, and one that interprets their shames as a simple algorithm. Last winter on a popular Final Fantasy XI (herein also referred to variously as FFXI) forum, players of the massively multi-player online role-playing game, abbreviated as MMPORG or simply MMO, vented their respective playtimes, in a collective act of transgression and catharsis. The opening post posited the question: “How much of your life has been wasted?” And there was no shortage of cringing and self-loathing as the numbers, staggering and almost pornographic in their respective volumes, came rolling in: 601 days; 538 days and 21 hours; 615 days and 19 hours; 676 days; 1024 days (but with “lots of AFK1 time!” the poster insisted.); 573 days, 785 days, 443 days (“no AFK,” this poster admits, with some chagrin); 663 days; 613 days, 2 hours, 5 minutes; 577 days; 256 days; 549 days, 19 hours, 2 minutes; 839 days, 19 hours; 467 days, 21 hours, 12 seconds; 984 days, 15 hours, 16 minutes, 6 seconds; 1081 days, 10 hours, 7 minutes, 5 seconds. And mine just as flagrantly obscene, sits, as of this writing, at 586 days, 14 hours, 46 minutes, 11 seconds.

There’s a function reviled by nearly all Final Fantasy XI players, tucked among 24 others on the main screen menu: one small, innocuous-looking icon that reads “Play Time”; a button that seems to hold all the dark secrets of that particular player, and one that interprets their shames as a simple algorithm. Last winter on a popular Final Fantasy XI (herein also referred to variously as FFXI) forum, players of the massively multi-player online role-playing game, abbreviated as MMPORG or simply MMO, vented their respective playtimes, in a collective act of transgression and catharsis. The opening post posited the question: “How much of your life has been wasted?” And there was no shortage of cringing and self-loathing as the numbers, staggering and almost pornographic in their respective volumes, came rolling in: 601 days; 538 days and 21 hours; 615 days and 19 hours; 676 days; 1024 days (but with “lots of AFK1 time!” the poster insisted.); 573 days, 785 days, 443 days (“no AFK,” this poster admits, with some chagrin); 663 days; 613 days, 2 hours, 5 minutes; 577 days; 256 days; 549 days, 19 hours, 2 minutes; 839 days, 19 hours; 467 days, 21 hours, 12 seconds; 984 days, 15 hours, 16 minutes, 6 seconds; 1081 days, 10 hours, 7 minutes, 5 seconds. And mine just as flagrantly obscene, sits, as of this writing, at 586 days, 14 hours, 46 minutes, 11 seconds.

Of course, I too would like to claim the sanctuary of “includes lots of AFK time!” in the aggregate number, and to some degree, it’s true. However, to be completely honest, I’d have to admit that my AFK time probably only adds up to maybe, and a generous maybe, 20 percent of the total play time, making it roughly 446 real-life days spent completing quests and lengthy missions, hunting monsters or waiting for them to spawn, running long distances from town to town, chatting with other players in real time, standing around idly with a flag up looking for a party of players to join, and, once in a party, deep in the trenches of what we in the MMO-bubble call “the experience points grind”—making my character stronger with each experience level, trailing carrot-on-a-stick-like to get to the next to obtain some hard-earned piece of armor, weapon or spell, or to access a new area. The work is hard and the rewards are tempered to keep you hungry, but sometimes they are great. This is a world of Dungeons & Dragons-like fantasy, where orcs and goblins run rampant over the land alongside temperamental insects and rabid bunnies—that is to say, amok and unfettered—a land of haunted pasts and doomed futures, a virtual universe fully capable of engendering its own heroes, enemies, sages and idiots, bitter rivalries, friendships, social hierarchies, and a seething brand of abrasive elitism specific to MMOs (and maybe audiophile web sites and high-fashion forums), and all packaged neatly into a game that slips its way into your house and then fights to the last splinter to stay within these walls. Final Fantasy XI is the House of the Rising Sun, and it’s been the downfall of many, perhaps better, people than me.

But this is where the story ends. As of July 1, I’ve officially quit FFXI after four long years. And I’ve procrastinated enormously in writing this article, and it was difficult for a long time to figure why I was so loathe to unload this heavy weight from around my neck. But the fact is, there’s a lot of guilt, a lot of owning up to involved in writing this sort of memoir of the last four years, as well as digging up bad memories and things I tried to escape from by diving so deep into an alternate world. So this is to be my confessional for all those times I was disappeared…

It would be hard for me to quantify the amount of heartbreak induced, time wasted, opportunities missed, and potential jobs lost due directly or indirectly to my four years playing FFXI, but I’m sure if I could, they would include: living on about $15 a week (or perhaps less––I could usually make $2’s worth of pasta last two days) because I wasn’t all that eager to find another job and had convinced myself that all writing jobs in San Francisco were insulting and garbage; barely making rent each month as a result; telling myself that the $14 a month I spent on FFXI subscription fees was cheaper than going out to bars and being social (which was true); stopped talking to most of my friends or avoided them in turn for FFXI; missing many a fantastic sunset while sitting on my floor, occasionally squinting through my (usually closed) blinds toward the gorgeous view I had of Twin Peaks, but more likely staring at the FFXI chat window; quitting my only job as a bike messenger; missing pickup games of soccer in Potrero Park and pickup games of softball in Oakland with friends; driving three roommates out of my house by being a curmudgeonly hermit; nearly missing seeing one friend a week before he died; missing seeing another friend one day before he nearly died after getting run over by a motorcycle. Want to know what I was doing all those times I said I couldn’t make it out to meet you? Well, it’s probably a good guess I was at home playing FFXI.

1. AFK: Time spent Away From the Keyboard with the game on.

Of course, as the story usually goes, it wasn’t always this way. This kind of addiction (and that’s what it is) always starts simply and innocently enough, doesn’t it? Final Fantasy XI was the first online role-playing game in the hugely successful series of Final Fantasy games, dating back to 1990 on the original Nintendo console. (I can say, with some pride, that I borrowed this game from some girlfriend of my cousin’s, and I finished it after playing obsessively for only a few months, with no guidebooks but pure skill and intuition. I also never gave the game back and wish I could be playing it right now.) Final Fantasy progressed with the Super NES system, but peaked on the original Playstation with Final Fantasy VII—a game that spawned a franchise of animated movies, sequel and prequel games grouped together under the same name, and, much to the disgust of most FFXI players, a long history of character name-stealing (Ask any FFXI player to relate how many variations of “Sephiroth” one sees in any given town). Generally hailed as the best of the Final Fantasy games, both for its storyline and innovations it brought to the traditional RPG (role playing game) platform, FF7 is the Holy Grail for hardcore Final Fantasy fans. I finished FF7, along with the following Final Fantasy 8 (which I actually liked better), about five years after they were released. Two years later I skipped ahead to the world of FFXI.

Of course, as the story usually goes, it wasn’t always this way. This kind of addiction (and that’s what it is) always starts simply and innocently enough, doesn’t it? Final Fantasy XI was the first online role-playing game in the hugely successful series of Final Fantasy games, dating back to 1990 on the original Nintendo console. (I can say, with some pride, that I borrowed this game from some girlfriend of my cousin’s, and I finished it after playing obsessively for only a few months, with no guidebooks but pure skill and intuition. I also never gave the game back and wish I could be playing it right now.) Final Fantasy progressed with the Super NES system, but peaked on the original Playstation with Final Fantasy VII—a game that spawned a franchise of animated movies, sequel and prequel games grouped together under the same name, and, much to the disgust of most FFXI players, a long history of character name-stealing (Ask any FFXI player to relate how many variations of “Sephiroth” one sees in any given town). Generally hailed as the best of the Final Fantasy games, both for its storyline and innovations it brought to the traditional RPG (role playing game) platform, FF7 is the Holy Grail for hardcore Final Fantasy fans. I finished FF7, along with the following Final Fantasy 8 (which I actually liked better), about five years after they were released. Two years later I skipped ahead to the world of FFXI.

Game company Square Enix (SE) introduced Final Fantasy XI in May 2002 to the Japanese Playstation 2 market, ushering in the company’s first MMPORG. In November, SE released FFXI for Japanese PC users before bringing it overseas to North American PC users a year later. (In March 2004 SE later released FFXI for North American PS2 users, and required a 40-gig hard drive attachment to play.) It’s a common complaint in FFXI that SE favors Japanese users, and the later North American introduction seems to support this, yet after five years of bitching there really is little empirical evidence to support this theory (but that doesn’t stop NA players from claiming it anyway). In 2008 FFXI has undergone its ups and downs, has lacked a true player vs. player mode (which, in MMOs like World of Warcraft, spawned such characters as this guy: the World’s Greatest Paladin.), has outdated graphics, and is probably past its prime as far as its online population goes, but it’s still ranked fourth in all MMO subscriptions. In the virtual world industry that generates more than $1 billion each year in subscription fees, FFXI holds its own against newer games like World of Warcraft and Lord of the Rings Online, owing mostly to its cross-platform capability—which is a success first achieved by SE.

Players who make up the virtual population of Final Fantasy XI are split among 32 servers. Although it’s possible to switch between servers for a nominal fee, most players stay on their original world—once relationships with other players are kindled and built, cooperation and teamwork engendered, and a good reputation (really the only form of karma in these games) established, it makes it difficult to start all over again. Most server transfers are players seeking to join their real-life friends for some virtual-action, or players who screwed over others and are more or less exiled on their current server. Like most other MMOs though, reputation follows cross servers, mostly though the use of gamer forums like the one at Blue Gartr Linkshell.

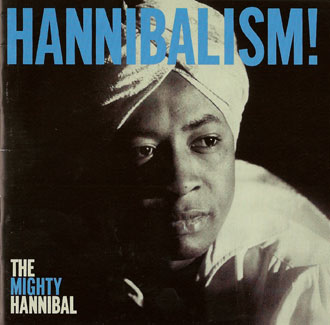

I started playing FFXI in June 2004, about a month after finishing my master’s degree at UC Berkeley. My roommate Buzz started playing about a week after me, and we’d spend a few hours a week chasing each other around town, shouting “Where are you?” through the walls of our adjacent bedrooms while our characters chased down rabbits or ran from some orc that would eventually beat us to death. I picked an Elvaan character: a tall, elvish model with shaggy hair that looked giraffe-like when running (such characters were also popular for those with hard-ons for Legolas of Lord of the Rings, spawning such awful variants like the Sephiroth-phenomenon: Legolaselve, Legolass, Legolaskilla, Regorass—the Japanese iteration, apparently). I named my character Hannibalism, a name I stole from the discography by The Mighty Hannibal, a ‘60s soul singer from Atlanta, Georgia, who was once on the cusp of R&B greatness before heroin addiction sidetracked him. (Sidenote: The Mighty Hannibal still plays shows and maintains his own Myspace page.) I also may as well own up and admit that I originally reversed the names of the singer and record, but the name stuck, and to this day I still jealously guard it.

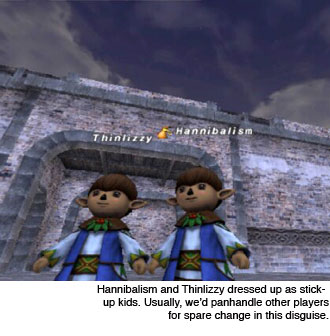

We played casually enough the first month or so. Hannibalism and Buzz’s character Thinlizzy ran around poking monsters with daggers and swords, experimenting with the huge array of equipment available in FFXI before we knew that certain jobs were more adept at particular types of weapons. These were the salad days of our time in Vana’diel—the happiness of ignorance, when the world was still huge and ever-expanding, before we reached the other side of the map, before we realized just how intense this game could be; there was so much to be explored. We ran from zone to zone, getting lost in areas we called “Orc Town” or simply, “The Woods,” fighting monsters we couldn’t kill, made intrepid journeys to other towns through dangerous and mysterious lands (we had no maps and didn’t know we could buy them), met other players and joined a linkshell—essentially a guild or a clan made up of a group of players who chat among themselves, do missions, level up, and kill monsters together as a team. Thinlizzy was booted from the linkshell pretty soon after joining, but I stayed, in a move that in retrospect may have been a blessing or a curse. As we learned more about the vast tapestry that comprised the game, our salad days dimmed and all it would take was one event to bring those blissful days of our characters’ naivete to an end.

But addiction can be a nebulous charge, especially when used in the context of things like video games that are pleasurable, but not overtly dangerous (Recall The Onion’s “I’m Like a Chocoholic, but for Booze” article). Even as countries like South Korea, China, and Vietnam work to curb gaming, what makes video games more addictive and dangerous than television or Internet forums or Internet porn or fucking, for that matter? Florian Eckhardt, a writer for the gaming site Kotaku.com—among the more skeptical of the powers of game addiction—responded to an interview request for ITV, a British news station, in a similar vein. “If that’s your question—‘Are games psychologically addictive?’—then the answer is yes. So is reading. So is watching television. So is opera. So is basking in the sun. So is sex. So is scratching your crotch. And so on.

“In short, the entirety of the best of human experience is addictive, because humans are both chemically and psychologically addicted to pleasure. So then the question becomes: is that addiction a bad thing, or worse than any other sort of psychological, pleasure-driven addictions?”

This past June, the American Medical Association rejected categorizing video game addiction as an official mental disorder stating, “There is nothing here to suggest that this is a complex physiological disease state akin to alcoholism or other substance abuse disorders, and it doesn’t get to have the word addiction attached to it.” Still, one would be hard pressed to say video games, MMOs in particular, don’t have addictive aspects—many a tale of woe, relationship and work failure, disenchantment, gross procrastination, and falling out has been blamed on video games. In fact, I blame FFXI for my taking so long to write this article—if I wasn’t killing mobs in Vana’diel with a great katana that resembles a giant paper cutter, I was trying to avoid saying anything at all about the game, knowing my self-loathing at realizing all those hours (well, years) spent, those picturesque sunsets missed, friends I not so convincingly evaded, all the heartbreak I tried to bury, it would all come bubbling to the surface, and frankly, I couldn’t bear to deal with it. I’m just a man. But it wasn’t FFXI’s fault, not the game developers, the other gamers, the tantalizing treasures that were oh-so-Sisyphean-close. It’s always more complex than that, isn’t it? And could it be that FFXI and other MMOs fulfill other roles than of a homewrecker or fodder for spirited debate and anguishing argument?

It’s usually some kind of traumatizing event that drives gamers over the edge of fun obsession to a darker world of full-on addiction. It’s true that games, MMOs in particular, are at least designed to be somewhat addictive—MMOs survive on monthly subscriptions, and it makes sense from a marketing perspective that there exist hundreds of lengthy, time-consuming quests, long series of missions with difficult bosses and obstacles, and some methods of obtaining high-quality gear that can sometimes take years to acquire. Repetition thrives in FFXI as it does in all MMOs: particular monsters that drop special armor or weapons usually do so at random, which we would attribute to luck—both bad and good, usually bad—and can take from 1 to 72 hours to respawn. Many hours of my game life have been spent standing with over 100 other players in an otherwise empty room for three hours waiting for Fafnir or a giant turtle, to pop. Many of us in FFXI’s endgame linkshells would agree that claiming these special monsters2 or finishing a long series of missions and receiving the rewards and status is worth the countless hours of waiting, the tireless patience, and the endless cursing of the game’s creators. Others would say it’s built into the game mechanics itself. “One of the first things that [game makers] did was take the ends away, and because the games could have no end they could last forever,” says Elizabeth Woolley, founder of Online Gamers Anonymous, a support group and message board for video game addicts and their families. MMOs take advantage of the non-linear gameplay, allowing special monsters and quests to be killed or repeated ad infinitum—usually after completing a long series of requirements. “Games are made as an entity to make money for the gaming companies without regard for their customers. [Game makers] are no better than drug pushers who get people addicted to buy their product.”

Woolley, who lives in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, has good reason for her quest, in this case raising awareness of the addictive powers that video games, and MMOs in particular, seem to draw. Her son Shawn was addicted to EverQuest, an early sword-and-sorcery MMO, a precursor for games like World of Warcraft and FFXI. On Thanksgiving morning in 2001, after several attempts at getting Shawn help, including a stay at a group home and more than a few appointments with different psychiatrists, Shawn shot himself in front of his computer while EverQuest continued to play out onscreen. “After he died, I found him sitting in front of the computer with the game on in his apartment,” she said.

I interviewed Woolley via telephone after contacting her through the OLGA web site. After Shawn died, Elizabeth, very much in the same vein as the protagonist in Dennis Cooper’s short novel God Jr.3, attempted to make sense of his game life. She sought clues in the game about the life he was living up to the moment he shot himself. She tried to trace his EverQuest life but was thwarted by the game’s privacy policy. He had left names written on paper by his desk—”Phargun,” “Occular,” and “Cybernine”—but she couldn’t figure out if they were places or players he had come across during his EverQuest gaming. Instead of building out of confusion and guilt over a child’s death a grotesque monument based on stoned schematics that may or may not have been drawn by the protagonist’s son as in Cooper’s novel, Elizabeth started Online Gamers Anonymous, which, even on just a quick glance, is not lacking for horror stories of game addiction ruining people’s otherwise healthy lives.

Shawn had a pretty normal upbringing, Elizabeth told me. “We were the first on the block to have a computer,” she said. “We didn’t really have any of the console games; if you wanted to play games you had to use the computer. Everyone had their share of the computer so nobody could play too much.” It wasn’t until Shawn started playing EverQuest that he began having problems, Elizabeth said, and she could see a change coming over him, both physically and socially. “His personality changed, he became a different person,” she told me. “He [used to be] concerned about his future, looking forward to the future, he was participating in his real life. Then he started playing, and that’s all he did was play that game. He had an apartment; he got evicted. He quit his job. His personality changed and he was withdrawn. He didn’t want to participate anymore.”

2. Note on FFXI claim system: Linkshells (or players) that first claim monsters have dibs on the kill and therefore the special items that may drop. If the original LS fails to kill the monster or otherwise dies trying, the mob is up for grabs—which sometimes leads to other linkshells trying to sabotage another group’s kill.

3. “People seem to need tragic strangers in their lives. They’ll superimpose tragedy when there’s nothing to prevent them…. Whoever thinks I killed my son has disappeared into oblivion. I just decided that oblivion was deciding not to walk, fuck, go to the bathroom by myself, or want to do any of those things again.” The Crowd Pleaser, God Jr. p. 16

GOD JR.

For me, the addiction came on not as a result of the game itself, but through happenings in my real life. I finished graduate school a couple months earlier and was floundering in my attempts to find a decent and rewarding writing job in the Bay Area. I was convinced the blog phenomenon made everyone think they were a born writer, and the pay scale (I recall reading one Craigslist post that offered “50 cents per page”) sagged as a result. Graduate school hadn’t been exactly uplifting either—I left not feeling entirely satisfied with my $48,000 investment, thinking that although we had the legendary Clay Felker as the chair of UC Berkeley’s magazine program, I was basically being sent off with a hand shake and half-hearted wish of luck in finding work. I didn’t leave with many contacts and left with fewer friends, one of whom was Simon Kinsella, who, along with Fanzine editor Casey McKinney and I, used to be a kind of Hydra head of sorts at the school. We related to each other in the kind of unspoken understanding of outcasts who didn’t really belong there amidst some our more ambitious classmates—not that we didn’t have our own ambitions and high expectations—we just hoped we could get through it all before others around us noticed. We regarded writing as some high art, something that needs and takes time to craft into near-perfection, perhaps the luxury of too much time or money, or an excuse of the lazy and unmotivated. Whatever the reason, I greatly respected them both as writers, friends, and drinkers.

It was a Friday night in August when I got the phone call. In perhaps a defining moment, I was playing FFXI when it came, dicking around in the Valkurm Dunes before going out to the bar. It was a classmate, a girl the three of us knew on various levels…why was she calling me now? School is over. “They found Simon,” she said over the receiver. “What do you mean found,” I said, annoyed in both the inscrutable nature of the call and that she was disturbing my game. “He’s dead. Simon’s dead.”

It wasn’t at that exact moment, but this announcement would later demarcate the beginning of the end for me. Off we went to Cincinnati, where Simon’s family lived, to see him get buried in an awful (not very Simon) Cliff Huxtable sweater, his body looking stuffed full of cotton, and us chainsmoking the tears away. Casey flew back from Barcelona, his summer vacation cut short after getting the news from my terse email: “Simon’s dead. You need to come back.” I still remember pulling away from the cemetery, turning on the radio and hearing William Shatner’s iteration of “Lucy in the Sky” interspersed with his commentary from an NPR interview. It was almost insultingly funny at that moment, Simon’s big joke on all of us: “When I die I want you guys to think of Shatner’s spoken word.” I seethed with bitterness from knowing he’d chumpatized4 himself the way he did—six months later when Casey and I finally acquired his autopsy report, which I still have, we saw that his last meal was probably a burrito and that he died from an accidental methadone overdose—and was overwhelmed with depression. Even today my reaction when I think of Simon approximates the fake Tony Wilson’s in the movie 24 Hour Party People when he’s told Ian Curtis killed himself: “What a stupid bloody bugger.”

For Shawn Wooley, it wasn’t death that drove him to the game. By Elizabeth’s account it was the game itself, and while there’s no question that games like EverQuest, Final Fantasy XI, and other MMOs are designed to retain their subscription base as long as possible, the debate has mostly moved on from whether they’re addictive or not (they are) and settled into the more nebulous and subjective realm of degree. For Elizabeth, there is no equivocation about the state Shawn was in while he was playing EverQuest. She took Shawn to psychiatrists and hoped they would help his addictive tendencies, but to little avail—they didn’t believe her. Shawn also had a history of epilepsy, a condition that worsened after he started playing EverQuest hardcore (it wasn’t called “EverCrack” by gamers for nothing), Elizabeth said, partially because he was playing so much he was neglecting his medication. “I wanted to get him committed for the game, but [the doctors] just laughed at me and said he didn’t have an addiction,” she told me. “They just kept telling me I should be glad he’s not addicted to drugs.

“Because they didn’t come up with it first, they say it’s not an addiction because its not in their DSM-IV [the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, technically the DSM-IV-TR] book. It’s not an addiction until they say it is when thousands of people are having problems with game addiction.”

Elizabeth later successfully put Shawn in a halfway house while he was recovering from his EverQuest binge. He didn’t have access to a computer there and was working on “getting back to normal”: looking for work, getting back in touch with his friends and family. But one night when she couldn’t sleep, Elizabeth discovered something incredibly unnerving. “ I got up one night at 2AM and decided to check my email. While I’m checking it, my front door opens and I’m just about to freak out because who could this be? And it’s my son.” Shawn was sneaking out of the halfway house and walking five miles in the middle of the night to play EverQuest while his mother was sleeping. Eventually, Shawn did start to recover. He started working again, and while still living at the halfway house, convinced his counselors he wanted his own apartment.

“I said don’t let him get his own apartment, but they said ‘He’s doing better, this is what he needs,’” Elizabeth said. ”And two months after he got his apartment he convinced them that he needed a computer, and after that he stopped all contact with everyone. He quit his job, quit all contact with his friends and us.” Shawn was 21 when he killed himself that Thanksgiving morning.

Elizabeth is of the school that believes game companies build addiction into their products, going so far as to use psychologists in development to make the game more addictive and to take advantage of people with social difficulties. “It’s not what I believe, it’s what I know,” she said when I asked her about her theories on game development. “Computer companies are using these people to put money in their pockets. They’re using brainwashing and mind control to get people addicted and buy their games.”

She takes a little bit of credit in lobbying Sony (the creator of EverQuest) to put warnings in their games about the dangers overplaying, which appeared in EverQuest2. There’s one in Final Fantasy XI, too—a gentle reminder (“Don’t forget your family, your friends, your school, or your work.”5) on a screen that’s easy to skip with enough button-mashing to get to the start-up and character selection menu.

“[Gamers are] so used to getting this rush they go back to their real life which is zero, negative, minus,” she said. “They feel like they have to go back to the game. Meanwhile they’re losing their real life, losing their relationships, losing their kids… They’re becoming cripples, physical and emotional cripples. It’s a part of their life the game takes away. Any real social interaction with people is done because they don’t know how to do it anymore.”

4. Chumpatize: taken from King of Kong, the documentary about two players battling for the crown of the legendary classic arcade game Donkey Kong; specifically borrowed from a quote by Roy “Mr. Awesome” Shildt, the former Missile Command world record holder.

5. In August, FFXI developers came under fire after one linkshell tried and failed to kill a notorious monster after 18 straight hours. The story of the vomiting that ensued, along with the statement in July of Sage Sundi, a senior FFXI game master, claiming a different notorious monster could take 18 hours as well, was picked up by gamer and news sites and subsequently blew up over the Internet. In response, a linkshell member named Rukenshin, a sort of sage himself in the FFXI community, wrote: “The fight did in fact last 18 hours, but people were not sick beforehand. No one mentioned feeling any kind of sickness until after we realized we’d have to give up, although many were reaching breaking points and starting to get exhausted. I think it goes without saying that the adrenaline of getting to the end of the fight was covering up what people’s bodies were trying to tell them.”

FINDING OBLIVION

Maybe the God Jr. quote could be more appropriately applied, with some adjustments, to me. “I just decided that oblivion was deciding not to eat, leave my room, talk to people and live a normal life, or want to do any of those things again—for a while.” With a long history of deep depressive episodes in hand, I consciously decided FFXI was in my best interests after Simon died. I’ve always played video games since the original Atari 2600 up through the XBOX 360, but never was quite “addicted” to games due to the fact that I’m usually not very good at them. My history of broken PS2 controllers just this year can attest to this. Once, after breaking what was probably my third controller in a week and a half while playing FIFA 08, I told myself that I may as well quit FFXI now, and, with no controller to play, it should be pretty easy. But as a linkshell event loomed on the near horizon the next day, I broke down and walked a mile in the rain to buy another one.

I will readily admit that FFXI is a huge time-sink, and that much of the last four years was used playing it—and I was usually having a pretty good time. It’s impossible to calculate exactly how that time was spent, but it takes 801,350 experience points to take one job class from level 1 to 75, the highest level. I have three job classes at level 75, so that’s 3 x 801,350 = 2,404,050 experience points (exp). Final Fantasy XI also has a merit point system in place after you reach level 75, so you can customize your job with different and stronger attributes. The cost is 10,000 exp per merit point. I have 176 merits, so that’s 1,760,000 exp. Not including the amount of experience points you lose for dying (my character died A LOT) and the fact that SE lowered the total amount of exp needed to reach 75 three years ago, the total is roughly 4,164,050 exp. One could make a pretty good case against me here, but the fact is that I wanted that oblivion, I wanted that anonymous buffer between me and other users and in-game friends that FFXI afforded. I wanted the solitary confinement wallowing in my depression that FFXI allowed.

It’s very easy to blame the machinery and avoid the deeper issue of what causes an addictive personality to begin with—but facts are facts, and there’s substantial evidence of a long trail of wasted lives and broken homes left in the wake of MMOs. But while the anti-gaming contingent rails against the virtual worlds MMOs create, there’s little talk of the positive aspects games can provide. To an outsider, or a “gamer widow,” of which there are many, it’s probably an impossible argument to make, but legitimate claims do exist and not every gamer is an obsessive one who loses control of his life in order to better their virtual one. I’ve met mothers who play with their sons, husbands who play alongside their wives, people who have met in-game and gotten married (happily, I assume—they’ve since had a baby and quit the game). One couple I knew stayed in touch through FFXI while they were both stationed in different parts of Iraq. I’ve played with people from Japan, Germany, France, Iceland, and the UAE. I’ve played with entire families who play FFXI together and have been strangely witness to in-game friends’ law school graduations, new jobs, new cars, new babies.

One of my in-game friends started playing FFXI to keep in touch with her daughter, who lived in Germany, and whose husband was stationed in Iraq. My friend, who plays the character Autumnfairy, of a cute, diminutive race known as the Tarutaru, would be considered unique outside gaming circles in that she’s an older woman—a woman playing an MMO sounds strange enough—and plays quite a bit. I met Autumnfairy in the last linkshell I was in, one in which endgame was pursued regularly and obsessively and required a big investment of time and responsibility, and would often end up feeling to me like a third job. Autumn, whose real name is Kim, does have a unique perspective on the game—not only does she skew the image of a gamer being some acne-faced 15-year-old boy who locks himself in his parent’s basement—or perhaps more accurately, a college kid who never leaves his dorm room or the security of his cable Internet connection—or a ghostly otaku with newspaper covering the windows, she also represents some of the best social aspects the game offers.

One of my in-game friends started playing FFXI to keep in touch with her daughter, who lived in Germany, and whose husband was stationed in Iraq. My friend, who plays the character Autumnfairy, of a cute, diminutive race known as the Tarutaru, would be considered unique outside gaming circles in that she’s an older woman—a woman playing an MMO sounds strange enough—and plays quite a bit. I met Autumnfairy in the last linkshell I was in, one in which endgame was pursued regularly and obsessively and required a big investment of time and responsibility, and would often end up feeling to me like a third job. Autumn, whose real name is Kim, does have a unique perspective on the game—not only does she skew the image of a gamer being some acne-faced 15-year-old boy who locks himself in his parent’s basement—or perhaps more accurately, a college kid who never leaves his dorm room or the security of his cable Internet connection—or a ghostly otaku with newspaper covering the windows, she also represents some of the best social aspects the game offers.

Her daughter, who played the character Charissa, introduced Kim to FFXI as a way to stay in contact with her and her husband, who plays Potobato, while they were overseas. “It was a great way to be with them,” Kim told me over our Instant Messenger interview [which was edited for chat shorthand]. “Charissa also used the game to keep her mind off Potobato being away and in a foreign country. It was cheaper than phone calls and you could pretend they were right there.” In a way, they were—at least in the sense of seeing each other as manifestations of themselves as little Taru characters and adventuring together. As Kim played through the forests and deserts of FFXI, her family—both immediate and extended—started too. Potobato’s brothers, who play Jpizzle and Faustus, joined Kim’s son, who played Sparkx, as well as her son’s best friend and wife. Kim also works as a quality control officer at the Kaiser Pickle Factory in Ohio, as do her daughter and her extended family, as Potobato’s family owns Kaiser Pickles.

“We used to have an LS [linkshell] called ‘Family Affair,’” Kim said. I asked her how FFXI works in her life as a social aspect, and if it could operate as a sort of real substitute in a way for social interaction.

“I have noticed that as I get older and I have moved from Colorado to Tucson to Indiana to Ohio in 6 years that I have less time for real-life friendships,” she wrote. “It’s not like when you are young and everyone gets together every weekend, lol. And [FFXI] has not kept me from meeting new people here. I am not too concerned about the game anymore as much as I like the social aspect.”

Kim also knows how easy it is to slip into the darker side of gaming. Her son Sparkx started playing obsessively and was one of the reasons Kim moved from Tucson, where he lives, to Indiana. “My son was addicted to the game and would not get a job, and that is why I moved to Indiana to be with Poto and Charissa,” she said. “He had been divorced and was depressed and then found the game and that was it. I dealt with it for 1.5 years and finally moved. I sold his account and paid his rent. He did a flip and got so depressed he blamed it on the game. He started trying to get me to quit. He was angry.”

“Anything can be an addiction,” Kim explained. “I know if I don’t set aside nights to do things with Charissa that the quality of the time would not be as good if I were playing. It’s always ‘hold on 1 sec, gotta raise someone.’”

Other friends haven’t been so capable of maintaining a clear perspective on the game as a social construct, rather succumbing to it as a social contract with responsibilities and a conscience that more or less forces you to keep playing rather than draw a line. Another friend of mine, who played the character Turaeg, was trying to quit since December of last year, and finally, exhausted, gave up his character to another LS member this summer. I interviewed him, also over IM (which was mostly left unedited for chat shorthand), at the cost of sending him my entire catalog of Guided By Voices records (which, including the Robert Pollard solo stuff, was about 18 albums).

Other friends haven’t been so capable of maintaining a clear perspective on the game as a social construct, rather succumbing to it as a social contract with responsibilities and a conscience that more or less forces you to keep playing rather than draw a line. Another friend of mine, who played the character Turaeg, was trying to quit since December of last year, and finally, exhausted, gave up his character to another LS member this summer. I interviewed him, also over IM (which was mostly left unedited for chat shorthand), at the cost of sending him my entire catalog of Guided By Voices records (which, including the Robert Pollard solo stuff, was about 18 albums).

Me: How hard do you think it is to quit ffxi?

Turaeg: It’s very hard. It seems like whenever I get to the breaking point of wanting to quit it throws me a bone.

Me: Like what?

Turaeg: I always think I just have a failure of will. Like around christmas I wanted to quit

then I got Morrigan’s robe and a lot of debt.

Me: yea but it’s ingame debt haha there’s no creditors who will hound you

Turaeg: Like I just now paid back Almaa what I owed lol. yeah, but you don’t just slight someone doing something for you in good faith

9:30 PM

Me: so you feel responsible for your virtual interactions?

Turaeg: Certainly, there’s someone on the other end of that character that put in just as much time as I have. I feel responsible enough that I would stay and try to pay back, if I had the time to put into it.

Me: do you think the game designers made it purposely addictive haha

Turaeg: definitely that’s why drop rates are so low. They are designed to be that slight ray of hope to string you along.

Me: i guess it’s relatively healthy as far as addictions go

Turaeg: it’s only socially destructive instead of possible bodily harm, unless you are korean and you just play instead of eating or sleeping lol

Me: why do you say socially destructive haha

Turaeg: how many r/l [real life] plans have you cancelled or turned down, because oh I have an event tonight, my ls needs me

Me: how many have you

Turaeg: I don’t keep count, but I really don’t plan stuff for monday or weds, and I don’t really talk to my friends about my online persona.

Me: I know for me for a while that’s all I did. I’d make up lies about why I couldn’t go out… but that was during a pretty introspective period of my life when I really didn’t want to go out, or was too broke to do it

Turaeg: you have the whole (vitrtual) world at your finger tips, why would you need to go out lol

Turaeg: Let me finish this exp party real quick…

Turaeg, whose real name is Andrew, lives in Illinois and started playing FFXI after he finished high school after tooling around with other MMOs like Phantasy Star Online (“though I question whether that’s a real MMO,” he said) and Ultima Online. In my opinion, Andrew doesn’t fit the bill for a stereotypical gamer, either. Like Kim, he seems well-cultured, intelligent, and has good taste in music and film (was once crushed out, Rushmore-like, on a high school teacher), and although I constantly make fun of his job at a factory that fixes waffle irons (he also once complained to me that he didn’t get hired to collect shopping carts in a supermarket parking lot and I had to explain to him that those jobs are for 14 year olds on summer vacation, homeless Vietnam vets, and senior citizens who have nothing else to do but die), he lives a pretty enviable and free young life as a 21-year-old indie rock kid.

Still I, at 30 years old, and he struggled with the same dilemma. Although I used the game during my own depressive episode exactly as I wanted to, I now wanted to leave it, but found its invisible fingerlings tugging at me whenever I conjured up the thought—and no amount of self-loathing kept me from picking up the controller.

Me: how long have you been playing

Turaeg: 420 days 5 hours 4 minutes 59 seconds. For awhile I just left my ps2 on

so the number is skewed.

Me: yeah me too but i think afk time can’t comprise more than 1/5 of total time

Turaeg: yeah i always dread to look at the play time. It’s kinda depressing. Literally spent a year engrossed in the game. It’s the exact opposite of what the warning thing tells you to do.

Me: yeah but who listens to that really

Me: i think for a while [FFXI] had a social function, i’m not really sure how legitimate of one it is. I mean the kind that can be justified?

Turaeg: like it serves a purpose?

Me: yea, aside from gaining things in game

Turaeg: yeah, more of an escape kinda, it’s really uninhibiting because of the degree of anonymity you have. I’d consider quite a few people in-game real friends.

Turaeg: I talked to more people on XI when my cousin died than I did irl [In Real Life]

1:15 AM

Turaeg: It definitely feels easier to communicate more openly with someone who you won’t see face to face you can communicate problems that you would feel uncomfortable talking to friends or relatives about

Turaeg: there was some kind of “other” aspect to ffxi

THIS IS THE LAST MMO I’LL EVER PLAY

THIS IS THE LAST MMO I’LL EVER PLAY

Oh yeah, there’s that “other” intangible aspect that FFXI and MMOs in general seem to possess. Is it the result of psychiatrists tweaking the game mechanics to keep us hooked or something else, a weird aspect to consider in the face of all the negativity surrounding MMOs, the fact that the game just might actually be enjoyable to some people? And that some people already consider online interactions through FFXI legitimate and still live pretty normal everyday lives? Mikeal, the leader of my last linkshell, has an astronomical playtime, organizes a group of about 35 LS members, built and maintains the LS web site, works full time as a network administrator, recently bought a new house in which he lives with his girlfriend, takes exotic vacations, is a huge Detroit Red Wings fan and once paid $500 for standing-room only “seats” at game five of the Stanley Cup Playoffs. If one believes—as does Dr. Maressa Orzack, a clinical psychologist who runs Computer Addiction Services in Massachusetts and is also an assistant professor at Harvard6—online video games are inherently addictive, this certainly doesn’t sound to me like the makings of someone who is addicted and at the mercy of an MMO. Granted, not everyone makes as much money as Mikeal does, but I don’t believe the opposite is necessarily true if you don’t—that if you’re a gamer you are one who doesn’t take vacations, own houses, have a girlfriend et al., that you’re slumming away in a virtual world, locked away from your family and friends, destroying your life.

Take, please, the case of my friend Kat, who plays the character Ceaira, of the race of female felines known as Mithra in FFXI. (Since most smart FFXI players consider female gamers to really be dudes in disguise, they are usually referred to as “Manthras.” Ceaira, however, is actually played by a female.) I met Kat as Ceaira shortly after Simon died and she’s one of the first players I knew in the game, and I consider her a close friend. I don’t know if I would invite her to my wedding (she lives in Minneapolis), but I’d definitely invite her out for beers. We used to talk quite regularly over the phone, mostly about FFXI goings-on and at our prime probably played about as hardcore. I also happen to know a lot about Kat as a person: i.e. I know when her birthday is (the same as my girlfriend’s), how old she is (about my age), that she’s a Korean girl adopted by white parents, that her brother is also a Korean adoptee who she used to live with and is a fat, disgusting slob, that she goes to visit her parents every Sunday to have breakfast with them, that she can repair sinks and put in new windows, that she once had a boyfriend who never put out, that she works as a server at an Italian restaurant that could be doing better, that she now lives in an apartment on her own with a cat named Lilly. Kat is also one of the most obsessed players I’ve ever come across in my time in Vana’diel.

Kat has four jobs at level 75 and almost 100 more merit points (that’s 1 million experience points) than me, but her playtime doesn’t really reflect this—owing mostly to the fact that she turns her PS2 off when she’s done playing, whereas I tried to kill my Playstation by usually keeping it on 24/7, even if I wasn’t playing, simply because I didn’t want to wait through the five or so minutes it took to start up and log in when waking up or coming home from work. (This also accounts for a good amount of my total playtime. Surprisingly, my PS2 is still going strong.) What was always amazing to me was Kat’s level of emotional involvement in FFXI, to the point where I repeatedly had to verbally question why she would get so invested in that aspect of the game. “Kat you can’t get so involved with this game,” I would say. “ You need to take some time off or something. You can’t let people bother you this much.” This was usually following some bombastic emotional outburst or an argument through FFXI chat that edged on a full-blown screaming match, and then usually logging off in anger and then not answering the phone when I called her. Kat cared so much about her friends in FFXI, took every perceived offense and friendship so personally, and pursued a few relationships through the game, against which I repeatedly strongly advised. It didn’t matter; to Kat some of these players, anonymous behind their character’s faces—avatars at best—were her closest friends.

6. In an interview, Dr. Orzack stated: “They design these MMORPGs to keep people in the game. I do think the problem is tied in with other things like family issues, but the games themselves are inherently addictive. That’s ultimately the cause of the problem.” Dr. Orzack didn’t respond to queries for an interview from this reporter.

“I think my persona outside the game shows in who I am in the game,” she told me in one of our many phone conversations for this article. “I’ve definitely been conditioned to be a caretaker my whole life. With mage people [healers and support jobs], you spend a lot of time care taking people. You feel a lot of personal responsibility.”

“I think my persona outside the game shows in who I am in the game,” she told me in one of our many phone conversations for this article. “I’ve definitely been conditioned to be a caretaker my whole life. With mage people [healers and support jobs], you spend a lot of time care taking people. You feel a lot of personal responsibility.”

Kat definitely takes care of people in her real life. She picked up the family slack from her brother when he was too busy eating fast food or selling Hondas, picked up the responsibilities her father was left unable to do when he fell ill, putting in new windows throughout her parent’s house and re-doing the bathrooms. And still she would often tell me she felt unappreciated in her family, that her brother was getting a free ticket while she was stuck doing the grunt work that went unrecognized. My assumption was that she turned to the game to deal with the fact that she felt neglected in her real life. But it was a lot deeper than that, and more pervasive than I originally thought.

“My dad has a nerve disorder—in the last 5 years he’s aged like 15,” she said. “I really liked building things with my dad; those little projects, fixing the roof, installing the sink, fixing the plumbing. I think FFXI served as a cheap distraction, a social distraction for people to get away from economic and social problems.

“It was so painful for me because when you’re a little girl you always think your dad is strong and will always be there and then you see him getting older. Now he has a rare nerve disorder; they don’t know what causes it and they don’t have a cure. He’s in so much fucking pain, he can’t taste anything. His tongue is numb. You hope it doesn’t happen but you’re helpless to do anything about it.

“I got really pulled in when my father got put on all those medications,” she continued, “and it hurt to think about it and see him like that. So it’s like, why not be Ceaira where everybody cares and loves me when I didn’t want to deal with my father’s problems because it hurt me so much.”

It goes back even further, she told me, to the fact that she’s adopted and retains a certain amount of lingering feelings of rejection. But it still doesn’t explain her actions in game, why the things that upset her would do so to such an extreme degree, and why she felt so much personal responsibility for her character. Normal in-game interactions are usually taken with that same buffer of anonymity one comes to desire in online situations—the ironic layer of separation that allows one to feel more like himself—but for Kat it was never that way—everything meant so much to her and had the potential to drive her to tears and I wanted to find out why.

Last fall, Kat dropped out of the game without warning for two months, which is about six weeks longer than any “break” I took from FFXI. We were still pretty good friends in the game then, and I was still playing pretty regularly so it was strange to see her missing in action. It wasn’t until a week or so later that I found out one of her in-game friends was in a car accident and had died. When I finally talked to her she told me she had just been up all night crying and drinking alone.

It was building up over the previous few months, that Kat was drifting away from our friendship and focusing more on people she met in a linkshell primarily made up of players who lived in the UAE, eventually going so far as to switch her work schedule around so that she could play with them during the day (prime playing time in the UAE), which worked out better for her since she made more money in evening shifts anyway. But her friend, a guy from the UAE who played the character Sanctuary, was in frequent contact with Kat—they often talked over the phone or over MSN Messenger. Kat found out that he’d died about a week after the accident, through a mutual friend who expressed some reluctance in telling her.

“I never took breaks from the game, the only break I’d take is if I went on vacation or went out of town. So that two months was a big break. I just drank by myself and cried.”

You’re taking this too hard, Kat, I told her. You don’t really know these people and you probably won’t ever meet them. Why do you get so involved? We started playing heavily around the same time—me to delve deeper into my depression and her to get away from her own life. It was a long time before it started to make sense to me—that Kat played this game and was so emotionally invested because, while she genuinely enjoyed it and relished the relationships she could foster through FFXI, she was seeing her character as a real manifestation of herself. Whereas I mostly wanted to fight and kill every monster in the game (which I guess would make me a barbarian in real life), Kat wanted to meet people, wanted to interact with them the way she wanted to in her real life—and hoped others would treat her the same.

You’re taking this too hard, Kat, I told her. You don’t really know these people and you probably won’t ever meet them. Why do you get so involved? We started playing heavily around the same time—me to delve deeper into my depression and her to get away from her own life. It was a long time before it started to make sense to me—that Kat played this game and was so emotionally invested because, while she genuinely enjoyed it and relished the relationships she could foster through FFXI, she was seeing her character as a real manifestation of herself. Whereas I mostly wanted to fight and kill every monster in the game (which I guess would make me a barbarian in real life), Kat wanted to meet people, wanted to interact with them the way she wanted to in her real life—and hoped others would treat her the same.

“When [the game] starts to take over your personal life it becomes an extension of you,” she said. “Like how you choose to act through your character is an extension of yourself. When we started playing hardcore, for me, where I was in that point in my life, I had quit my job, broke up with my boyfriend [who was an alcoholic and never put out anyway], cut all my friends off from Rain Forest Cafe [where she worked for nine years], broke off my social connections. I didn’t give a fuck anymore because the game took over. The friends I lost in real life I gained in Final Fantasy.

“When it changed for me really was last summer when you stopped playing so much, started to work away from the game and made me realize that maybe I should start walking away from it, too. I had to realize that there were responsibilities like moving out and paying for utilities and my apartment.”

For me, I always knew that FFXI was just a matter of time—which turned out to be four years. For sure I was sucked in, for sure I played obsessively, sometimes until 6 AM, and many days for 12 hours or more. I knew that this would probably be the last MMO I’d ever play because I just couldn’t bear to justify and pledge this level of personal commitment to another game—to the point where I, as many other FFXI gamers I spoke to, considered it to be another real life job. But even after all this commitment I knew that eventually my self-loathing would overcome the obsession. For Kat, however, it didn’t seem to have that kind of timetable. FFXI seemed to be the only place where she was really happy, where she could be herself and not feel bad about who she was—and the more I prodded her through interviews to tell me why she was still so into the game while I was making my way out of it, the more I started to feel like I was taking away the only thing that made her comfortable with herself at this time in her life, and that made me feel like I was being an asshole. While I was trying to hammer away the reasons why I was quitting as universal truths that she needed to recognize simply for my selfish sake of feeling like I was justified, I realized I was in danger of hurting her and ruining our friendship.

“I was plunged so deep into the game, and just now I’m resurfacing,” she explained to me. “There’s a reason I don’t have a lot of women friends and that’s because they’re all catty, talking about fashion. This game was the only thing that turned my brain off. When you play the game and get entrenched as much as you and I did, you cut everything down to the minimum: You pay the minimum amount of bills, barely clean your room. What’s the bare amount of social contact you can deal with? And when you come back out, you can say I didn’t really miss that part, or maybe I do miss that part. I’ve never minded being by myself, even as a child I never minded playing by myself. By playing a game and not having a lot of real life friends, while you may call me a loser, it doesn’t really bother me, because that’s my personality. FFXI was a breath of fresh air for me.”

“I was plunged so deep into the game, and just now I’m resurfacing,” she explained to me. “There’s a reason I don’t have a lot of women friends and that’s because they’re all catty, talking about fashion. This game was the only thing that turned my brain off. When you play the game and get entrenched as much as you and I did, you cut everything down to the minimum: You pay the minimum amount of bills, barely clean your room. What’s the bare amount of social contact you can deal with? And when you come back out, you can say I didn’t really miss that part, or maybe I do miss that part. I’ve never minded being by myself, even as a child I never minded playing by myself. By playing a game and not having a lot of real life friends, while you may call me a loser, it doesn’t really bother me, because that’s my personality. FFXI was a breath of fresh air for me.”

And that’s when it really hit me—Final Fantasy was obviously more than just a game, an escape, or a distraction for her. This was really where she wanted to be, where she wanted to spend her free time without feeling like she was running from something else, the one sanctuary where she felt like it was okay to let her personality really shine. Who was I, an embittered, lonely, and chronically depressed 30-year-old man, to tell her to stop? She once told me how she used to be really social, active, going out and partying, getting wasted and running around with a crew who encouraged the same. But it was never her—it wasn’t the person she wanted to be.

“I kept trying to be what I wasn’t,” she said about that time in her life. “I always played by myself as a kid and my family always pushed on me that there was something wrong with that—that I should be a crazy extroverted person. It wasn’t making me happy; it wasn’t making me feel like I was who I was.

“What this game kind of honed in on me was that, yes, I was a homebody and that was okay. This game allowed me to be a homebody and be social. It’s not always a certain event that was a catalyst to making you a gamer [as it was for me], but rather it was something that you always wanted to be. Even though it enslaved you to playing whatever many hours we did, I think it freed me too.

“[FFXI] freed me from being fake, from being the makeup girl, from fretting about my hair, and what kind of purse I had. It cut down on what was important to me. I used to be crazy social, but to me it was fake. I kept being pushed to be social. When I started playing the game I got to push all that out.”

For me, I realized I could no longer continue the direction I was going. Yes, my points for quitting FFXI were valid. I had used the game for what I needed at the time and at some point, acquiesced and let the game take over—partially because I was having fun and partially because I just wanted to drop out. For Kat, the reasons were much more complex than just an escape from feeling hurt. It was more of a rejection of her past and an embrace of who she felt she really was, and her reasons for playing were significantly more valiant than my own.

I talked to Kat a few weeks after our interview sessions. In those last few days I was barely playing FFXI and she had since switched servers from me, but I wanted to catch up with her. “I’m more in control of the game now,” she told me. “ I can turn it off when I want to and I don’t care about what drops or what gear I have anymore.” Still, she spent about 10 minutes excitedly listing everything she had done in the game since we last spoke. Then she told me her piece of shit car had been stolen, as almost as an “Oh yeah…” moment. “But!” she said. “Check this out! With my insurance payment I bought a 2004 Accord!” She got it cheap, too. Few people, it seems, want to drive a stick-shift in Minneapolis these days. This, added with the news that some of her UAE friends from my FFXI server were switching to her newly adopted home, I had rarely heard her sound so happy.

Special thanks go to everyone who helped out with or patiently waited for this article, particularly my editor Casey, and FFXI friends Kat, Andrew, and Kim. My apologies for the shitty PS2 quality screenshots, though the nicer, high-res ones were given to me by Almaa.