Dusan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie comes to Criterion DVD

11.10.07

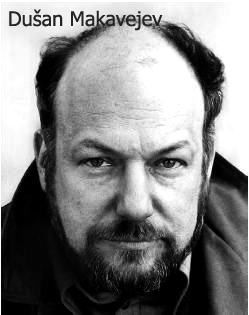

During the 1974 Cannes Festival, where Dušan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie premiered, the Yugoslavian director stayed at the Carlton Hotel, whose normal nightly rate for a single is currently about $450. The next year, he and his wife slept in a tent on the beach. “Some years Carlton, some years beach,” he told Roger Ebert with a shrug.

During the 1974 Cannes Festival, where Dušan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie premiered, the Yugoslavian director stayed at the Carlton Hotel, whose normal nightly rate for a single is currently about $450. The next year, he and his wife slept in a tent on the beach. “Some years Carlton, some years beach,” he told Roger Ebert with a shrug.

The reputation of a rebel––whose worth is ostensibly how much they can challenge a system’s mores and assumptions while still getting that system to acknowledge their existence––is often tenuous. Perhaps the widening scope of his work and an increased public profile made Makavejev available to more enemies than he had previously been; whatever the case, the response to Sweet Movie bordered on erasure, on rejecting the fly and ointment, on making him a persona non grata.

The New York Times called it “unfunny” and “boring.” Time magazine’s characterization of the film—“a social disease”—was pulpit rhetoric. Even people who should’ve been allies were put off. Otto Muhl, a founding member of the Vienna Actionists—the performance art group who vomit on a dinner table, poop on plates, and urinate into each other’s mouths during one segment in the film—called it “downright kitsch.” (Perhaps Muhl, who was jailed for child sexual abuse in 1991, didn’t think Makavejev was a truly psycho-liberated hardass.) The response was so negative that actress Anna Prucnal was exiled from her native Poland, and even denied a visit to her dying mother. Sweet Movie is still banned in England. The film’s attendant controversy is fascinating and significant. But thirty years of public disgust is a brutal handicap for proponents, and it makes serious discussion of the actual film difficult.

Sweet Movie—which was recently issued by the Criterion Collection, making it available on DVD for the first time—begins with a contest held by an abstinence organization to find the world’s most beautiful virgin. A series of hymens are inspected (earning the IMDb plot keyword “leg-spreading,”) and Carol Laure, playing Miss World, wins. Her prize is to wed Mr. Kapital, an idiot cowboy billionaire with a cleanliness fetish, whose marriage speech toasts Miss World as, “above all, a purified sanitation system for unchecked waste.” Miss World’s story is intertwined with Anna Planeta’s (Anna Prucnal), captain of the boat Survival, who sails in search of “sexual proletarians” left in the wake of communism’s failed ideals. After several attempts to board, a gamely sailor named Potemkin proves his worth by pissing off an embankment, and makes furious, public love to Planeta, who shouts, appropriately, desperately, what’s probably on the mind of all people who have sex within thirty seconds of introduction: “Fascination!”

And so on. They take different paths—Anna Planeta of political ideals and revolution, Miss World of passivity and commodification—but both end in insanity. Laure plays a mute, exhausted-looking doll for the second half of the movie, and when Prucnal exits, she exits screaming. Sweet Movie is, ostensibly, a cartoon: none of the characters are developed. All are, as Scott McCloud once wrote of cartoons in Understanding Comics, “amplified through simplification.” And it’s a visceral, sensorial film, too: Planeta and Potemkin lay in a swinging bed full of sugar, the Actionists have a food fight, and the last scene shows Laure rolling around while melted chocolate is poured over her for a television commercial.

And so on. They take different paths—Anna Planeta of political ideals and revolution, Miss World of passivity and commodification—but both end in insanity. Laure plays a mute, exhausted-looking doll for the second half of the movie, and when Prucnal exits, she exits screaming. Sweet Movie is, ostensibly, a cartoon: none of the characters are developed. All are, as Scott McCloud once wrote of cartoons in Understanding Comics, “amplified through simplification.” And it’s a visceral, sensorial film, too: Planeta and Potemkin lay in a swinging bed full of sugar, the Actionists have a food fight, and the last scene shows Laure rolling around while melted chocolate is poured over her for a television commercial.

Which is to say it’s a comedy. A beautiful, violent comedy with moral tethers: the lunacy of passion, the dangers of rebellion, the obscenity of money. Makavejev was trained as a psychologist but has the heart of an agitator, and for all the satire, political import, and aesthetic orgies the movie offers—he once stated that Sweet Movie was his “love letter to color”—its primary target is the mind of its viewer: what makes them self-conscious, what triggers protest from their sense of social grace. Most people don’t want to be thought of as that guy who likes that movie where children are seduced or full-grown women are breastfed or someone sticks a large piece of meat through his zipper and chops it up with a cleaver while onlookers gargle milk. (And thinking privately about what it would “mean” to be that guy isn’t exactly a welcome exercise either.)

But to call Makavejev an advocate of sexual perversity would be to miss the shapes forming under the noise. What one might call a perversion, another might call an act of liberation; what one might call a neurosis might actually be an expression of personal preference. All of it might just be what gets someone off. How he judges his characters is quiet, almost imperceptible: they act freely, but they all end up trapped, Potemkin by Planeta, Planeta by the police, Miss World by the people exploiting her. He’s sly about his equations: he includes the Actionists—one ideal of freedom, like it or not—but cannily puts them toward the end of the movie, as Anna Planeta gets increasingly sloppy and unattractive, and Miss World surrenders to porn.

Makavejev’s breakthrough film, 1971’s W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (also recently issued by Criterion) is a loose documentary about the Austrian-American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, who posited, roughly, that all human neuroses could be traced to a lack of both physical and psychological sexual freedom. Freedom, in Reich’s work, meant mindfulness, tenderness, and openness. This may or may not include throwing up but Reich certainly makes no mention of vomit as such. The sexual circus in Sweet Movie is an ambiguous statement, morally. It made some feel uncomfortable and voyeuristic and revolted; it made others feel inspired. Some, both. A friend once asked if the people in the movie were attractive. They are, but I pointed out that almost anyone is attractive when they’re doing whatever the hell they want.

Makavejev’s breakthrough film, 1971’s W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (also recently issued by Criterion) is a loose documentary about the Austrian-American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, who posited, roughly, that all human neuroses could be traced to a lack of both physical and psychological sexual freedom. Freedom, in Reich’s work, meant mindfulness, tenderness, and openness. This may or may not include throwing up but Reich certainly makes no mention of vomit as such. The sexual circus in Sweet Movie is an ambiguous statement, morally. It made some feel uncomfortable and voyeuristic and revolted; it made others feel inspired. Some, both. A friend once asked if the people in the movie were attractive. They are, but I pointed out that almost anyone is attractive when they’re doing whatever the hell they want.

The most resonant scenes in the film are when Makavejev’s sense of humor and violence are clarified by displays of universally digestible, unambiguous human passion. By unambiguous and universally digestible, I mean scenes you could reasonably watch with your aunt. After being stuffed into a piece of luggage and shipped to Paris, Miss World finds herself on the Eiffel Tower, where a singer named El Macho is shooting a video. For all the hysteria and asides––the director, a plump, effete Brit, prompts Macho to do something “terribly Mexican, very noble”–the scene is anchored by a silent smile Miss World and Macho share; Makavejev abruptly clips the music and alternates between close-ups of their faces. The silence is shocking not only because it focuses the mind, but because it reminds us that close-ups predate talkies. Then, of course, they decide to fuck standing up, on the observation deck, which prompts a “love cramp” for which they have to be pried apart with a muscle relaxant on a restaurant kitchen table surrounded by meat. An excited onlooker smokes a pipe, consoling the couple: “Happens to dogs, too.”

But for their passion, they’re traumatized; Macho can’t finish his song without dissolving into tears, and the scene ends with Laure wordlessly smashing eggs on her own face. Anna Planeta, sitting on the banks of the river with Potemkin, laments, “Everyone has deserted me.” True, there’s a political allegory happening here, too. Some critics felt like Makavejev’s historical allusions, especially the cut-in Nazi footage of Polish officer’s remains from the Soviet massacre at Katyn were pretentious—and they were pretentious, but the human resonance of horror comes before the historical. Sweet Movie isn’t all probing, all the time. The scenes featuring the Actionists are the hardest to take, but they’re also the least interesting. (Laure’s mother had committed suicide and her father had deserted her while she was a child; dealing with the communal Actionists, who impishly tried to have sex with everyone in sight, was so traumatizing for her she temporarily quit the film.)

But for their passion, they’re traumatized; Macho can’t finish his song without dissolving into tears, and the scene ends with Laure wordlessly smashing eggs on her own face. Anna Planeta, sitting on the banks of the river with Potemkin, laments, “Everyone has deserted me.” True, there’s a political allegory happening here, too. Some critics felt like Makavejev’s historical allusions, especially the cut-in Nazi footage of Polish officer’s remains from the Soviet massacre at Katyn were pretentious—and they were pretentious, but the human resonance of horror comes before the historical. Sweet Movie isn’t all probing, all the time. The scenes featuring the Actionists are the hardest to take, but they’re also the least interesting. (Laure’s mother had committed suicide and her father had deserted her while she was a child; dealing with the communal Actionists, who impishly tried to have sex with everyone in sight, was so traumatizing for her she temporarily quit the film.)

When the Sweet Movie DVD was released, a friend cautiously recommended it to me: “I won’t say anything about it, really, but I will tell you that I wouldn’t tell everyone to watch it, and that I think you’d understand it in a way a lot of people might not.” The idea frustrated me: If it’s good, people should see it. It is good; people should see it. It has beautiful colors. There are a lot of good jokes. It’s arousing.

But in its best moments, it burrows deep. It discomforts and embarrasses. The second time I watched it—and certainly whenever I’ve watched it with people—I became acutely aware of my reactions. What did I laugh at? Am I developing new -philias? Is this a good movie to audition dates? Critics of the film in 1974 weren’t being prudish—I don’t pretend to free love either, gross or otherwise—they were just being stupid. Not that there isn’t some psychological liberation to be attained, but it’s all in good measure, and all with implied consequences. Incidentally, the title isn’t any great irony. There are a lot of movies as severe as Sweet Movie, but none balanced by such skepticism and tenderness. The film’s essential metaphor is during the dinner scene with the Actionists: after a man feeds a sausage through his zipper and hacks at it with a cleaver, in a room full of screaming and vomiting Austrians, Laure takes his real penis and places it, gently and wordlessly, against her cheek.