Difficult Novel

28.06.12

Jonah was conscious of carrying a large novel into the cafe, worried how some people might consider that a reticent yet arrogant announcement he was making to those lesser-read, though that is hardly what he thought. He made sure the novel’s cover was firmly pressed against the side of his body while he waited in line, its grumpy and deceased author safely hidden from view. The barista, a recent college graduate whose septum ring seemed like two symmetrical boogers hovering perfectly in front of each nostril, wasn’t interested in the author’s life at all––how he lived with his mother and ate her hair; how he overdosed on sleeping pills; how he was either a- or bi-sexual, probably––and only concerned, not altruistically, but commercially, with what Jonah wanted. She looked at him with widened eyes to implicate the passing moments from which he should have ordered his drink by now. A popular acoustic song that guys who wear sandals and have mellow attitudes claim to really like played. The lyrics professed the songwriter’s feelings towards a girl who Jonah imagined as not very bright, and likely cruel; he became deeply irritated by the song, those glib proclamations of frivolous love, and felt further distanced from his generation. Now the barista was frowning. He ordered the coffee, smiled an apology, and made stifled efforts to keep the novel flat against his chest as he took three dollars out of his wallet, fanned each bill out as visual proof of their aggregate value, and dropped the 38 cents which was handed back to him inside a jar labeled “tips” spotted with smiley faces and flowers drawn by people who would claim they are artistic but have no drawing skills.

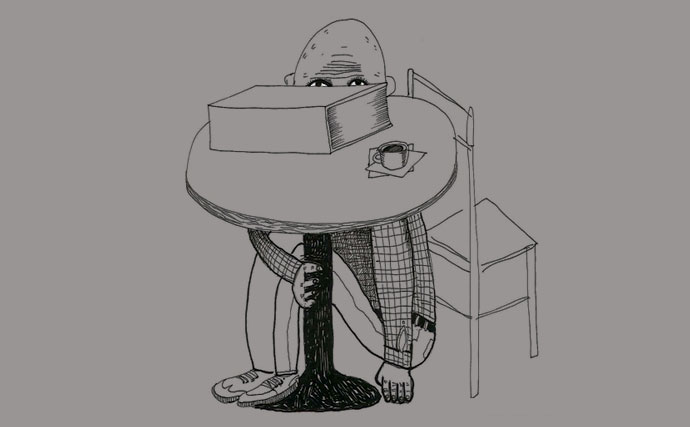

He sat down at a small round table and set the large novel face-down. From the back cover, a wordy blurb exuded its essential word “seminal,” and Jonah, perhaps influenced too much by porn, immediately envisioned semen in his coffee instead of cream. He sighed, felt gross, and looked over at an attractive woman clearly studying something difficult which involved calculators, highlighters, and sticky tabs. She looked miserable, not that her life was miserable––far from it; she was in a healthy committed relationship, was beautiful, came from a good family, etc.––just that she came to this cafe to do miserable things. Jonah preferred reading seminal novels in cafes instead of his apartment for this exact reason: people were temporarily made miserable by the things and people they were respectively studying and waiting for. He opened his book to page 587 and flapped through the remaining 321 pages, causing a barely perceptible indoor breeze on his chin. Jonah tried to be inspired by the novel again, to somehow induce the thrill he first had bracing the weight of the book in his hands in the bookstore––this warm rectangular nest in which he could remove himself from this life, into a world loyally and painstakingly transcribed by an author whose desperation at the words therein mirrored his own, each sentence a thread in the ultimate tapestry of better meaning. The old world, brutal, obtuse, was still here, eyeing him inside the cafe with its omniscient third. In this crude fiction, a young man was sitting alone in a cafe on a street named after a president, state, tree, or nut, in a town whose largest employer was the liberal arts university around which such cafes populated, hence patronized by the invoked student body. Jonah had smoothed out page 587 with his hand, then pinched the upper-right corner with index finger and thumb, long before it needed to be flipped, as if wanting the book to end sooner, to hurry reality to its end. It seemed odd, emotionally dysfunctional even, that someone would take a twenty-five minute bus ride to a more lively and populated part of town, the “main strip” as it was referred to, enter a cafe for the sole purpose of reading a critically heralded yet commercially obscure novel (the coffee was simply a “bonus,” or imperative measure to establish patronage), sit down to read, read a paragraph and a half, and begin to feel his heart wander towards the walls, and idly ache for a woman whose future, regardless of how she did on the test, seemed bright, reasonably bourgeois, and full of regular sexual intercourse with an adequate suitor. They would have well-mannered children, summers by lakes with boats by docks, a lot of gin without the alcoholism, all seen through the golden light of pharmaceutical ads. He closed the book and looked at the cover for the thousandth time.

Another woman who also wasn’t so interested in what Jonah was reading scrolled down in her phone’s social networking app, going backwards in time with quick flicks of a finger, from “4 seconds ago,” to “4 hours ago,” to June 12, or whatever date was yesterday, or the day before. Her coffee had been turned beige with cream, which Jonah found only vaguely sexual now. The song had changed to another one. An angry young man with leftist political hubris irresponsibly made allusions to anarchy while the bassist and drummer followed along with implied allegiance. No one seemed to notice the song, save the busboy loading dishes in the back (a metal shirt, metal in his face) clearly moved by the most emotive parts of the song, as corroborated by the airing of a cymbal’s crash at all the critical moments.

Jonah opened the book again, this time at page 591, trying to remember what had happened in the last three pages or so. “It’s like a god damn short story,” he thought, “three pages in which barely anything can happen.” He scoffed at short stories, the middle-aged women who tend to take workshops on its craft, and severely dove into his thick novel, this time with an almost violent intensity, as if he were being recorded by a panel of judges looking for serious readers to save the world from unexamined happiness in general. Soon he was outside of the words again. He looked at the negative spaces between the letters which formed the words, which formed the sentences, which––if one, bored and lonely in a cafe on a weekend afternoon, tossed out of his apartment by a gripping heart, continued outward like that––eventually formed blurry components of stories resembling rectangular patches of paragraphs as a kind of linguistic gauze meant to seal in some mental wound, either incurred by reading or living, he couldn’t tell. He hated this book.

“Macaroons,” he thought.

The two-booger girl looked sorrily at him, yet with an empathetic smile just at the end of an ambivalent stare. She knew the type: morose, both misanthropic and self-doubting, they come in around 3:45 p.m. with some crazy book and just sit there for hours looking at women, storing their countenances and other palpable aspects of their presence to masturbate to later on in collusion with visual stimulus from porn, imagining grossly unrealistic scenarios borrowed from fiction, but without all the high modernism. After twenty minutes, they always get up for a macaroon.

Jonah noticed her iPhone plugged into the speakers and smiled at her horrible taste in music, the trite adequately marketed ambiance for which she was responsible, this awful day. “Can I get a macaroon?” is the penultimate thing he said to her, followed fifteen seconds later by “thanks.”

He carried a medium-sized white plate with a macaroon rested in the approximate center back to his table, leaning from right to left in correlation with the evasion of backs of chairs, bags, and the occasional limb. He placed the plate in the approximate center of the circular table, thus positioning the macaroon in the conceptual, and somewhat actual, center of the table––its subconscious ray, or sentient force, emitted downward into the very stem of the table, into the floor, the concrete, the various geological levels of earth’s sediment, crusts, and mantles, into its very core, itself an arbitrary center absurdly approximating itself within an edgeless universe, eventually conceding to an oblong loop around a teenage star. The macaroon was half covered in chocolate (on the left side, from his particular perspective) which he imagined as the perfect cover for a book from which no National Book or Booker prize or Pen slash whatever award-receiving title could be extracted by these curious and relatively philistine eyes of the lesser-read, undoubtedly followed by implications about what kind of character he, Jonah, was. What kind of person carries a book that thick around, taking notes by hand on a yellow pad of paper as an attempt to resolve, or at least consolidate, the author’s penchant (a tic, really) for fragmented narrative, exacerbated by excessive syntax under the auspices of postmodern entropy or whatever words were currently being used to describe it all. Johan numbed his thoughts in the chocolate, and saw himself again from the omniscient third person perspective, slightly from above, shot with a warm lens, as if this scene, the past fucking hour here, were (edited, of course) from a Cannes-winning film whose poster was also modestly covered in chocolate; this went on and on, this inner whirlpool of self-obsession and world critique––the light turning rusty in the late afternoon, the sign language of its flickers typing “maybe tomorrow”––the macaroon now carefully being torn apart from its chocolate line, almost commemoratively, as if one were opening a large formidable novel.