Devotional Materialisms: on Thomas Hirschhorn’s Superficial Engagement…

28.03.06

Devotional Materialisms: on Thomas Hirschhorn’s Superficial Engagement…

Devotional Materialisms: on Thomas Hirschhorn’s Superficial Engagement…

(beginning in the form of a letter to Fanzine)

How with this rage can beauty hold a plea…

— Shakespeare

One must make a friend of horror.

— Chris Marker quoting Marlon Brando quoting Joseph Conrad

Mythical violence is bloody power over mere life for its own sake, divine violence pure power over all life for the sake of the living. The first demands sacrifice, the second accepts it.

— Walter Benjamin

I have been thinking a lot about the problem of submitting a journalistic account or account otherwise of Thomas Hirschhorn’s recent show at Barbara Gladstone gallery in Chelsea, Superficial Engagement (hereafter SE). What I admire about Fanzine is the extent to which it presents itself conversationally, and to this extent communicates things worth knowing in fresh and accessible ways. Yet there is something that has not allowed me to be so conversational or journalistically inclined (and that has in fact made me dread my critical freedom) in the face of Hirschhorn’s recent showing. Why have I dreaded so? Is it because SE brings to a head the deepest ambivalences I have felt about the US response to 9/11 and subsequent events: ambivalences which situate the artist between the exigencies of political effectiveness and the necessities of transcendence — our recourses to devotion, to the divine? Our resources.

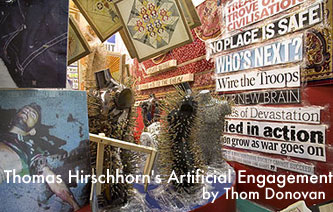

The thing about SE – and why I feel it to be one of the artist’s most important works to date, and perhaps a significant marking point for recent art at large – is that it aligns itself with two aesthetic tendencies, and in doing so goes beyond these tendencies, producing a third. The first of these tendencies is abstraction: the highly rational, beautiful, and “rested”-Classical. This tendency is embodied by a host of devotional reference points: Emma Kunz’s theosophical drawings, images from works of “color musicians,” as well as kitschy reproductions of 80’s “spiral art” and other post-“psychedelic” craft forms. Precariously, in a clash of culturally sanctioned forms (however “marginalized” or “outside”) and products of mass production, such references appeal to a power of the beautiful to calm, rest and inhere to it spiritual power – a metaphysical potential “to heal” Hirschhorn himself cites as one of the objectives of his latest work. The second tendency, a tendency arguably inverse of the first, presents through the most direct means (the artist’s signature materials: packing and other common household tapes, nails, screws, cardboard boxes, Sharpie, etc.) violent actualities — a severed head or a barely recognizable human body standing in a pool of blood; and in so doing burdens the viewer’s gaze with overwhelming images and signs of manifest violence. This phenomena Jean-François Lyotard may likely call the “presentation of the unpresentable,” and his contemporary, Emmanuel Levinas, an instantiation of the “there is” – the anarchic night of creation itself commensurable with ethical responsibility.

The thing about SE – and why I feel it to be one of the artist’s most important works to date, and perhaps a significant marking point for recent art at large – is that it aligns itself with two aesthetic tendencies, and in doing so goes beyond these tendencies, producing a third. The first of these tendencies is abstraction: the highly rational, beautiful, and “rested”-Classical. This tendency is embodied by a host of devotional reference points: Emma Kunz’s theosophical drawings, images from works of “color musicians,” as well as kitschy reproductions of 80’s “spiral art” and other post-“psychedelic” craft forms. Precariously, in a clash of culturally sanctioned forms (however “marginalized” or “outside”) and products of mass production, such references appeal to a power of the beautiful to calm, rest and inhere to it spiritual power – a metaphysical potential “to heal” Hirschhorn himself cites as one of the objectives of his latest work. The second tendency, a tendency arguably inverse of the first, presents through the most direct means (the artist’s signature materials: packing and other common household tapes, nails, screws, cardboard boxes, Sharpie, etc.) violent actualities — a severed head or a barely recognizable human body standing in a pool of blood; and in so doing burdens the viewer’s gaze with overwhelming images and signs of manifest violence. This phenomena Jean-François Lyotard may likely call the “presentation of the unpresentable,” and his contemporary, Emmanuel Levinas, an instantiation of the “there is” – the anarchic night of creation itself commensurable with ethical responsibility.

Considering the ethics of this second tendency – to present directly beyond ponderability, or comprehension: where to pre-hend, or grasp in advance of feeling, would be to violate the responsibility of voiding one’s gaze, witnessing beyond witness or looking awry — it is crucial the extent to which many of Hirschhorn’s Afghani and Iraqi figures are disfigured; that is, lacking faces as portals of commandment and absolute obligation. Instead, what may remain of obligation is a transcendental lack-in-excess, the excessive (non-)presences of photographed corpses striking-out an all-too-human economy of legal-moral retribution. Not only in the images of mutilation, but in the sheer volume of blown-up headlines embodying a thick fog of media warfare, the viewer is caught in the throes of a type of negative transcendence: a failure to transcend, to sublate or synthesize, a series of messages in excess of what they would say — noisy in their contradiction, tragically enjoyable in their paratactical (non-)sense-making. Between sublimation and a transcendent negativity, “Chromatic Fire” and “Concrete Shock” (the names of two of Hirschhorn’s three rooms at Gladstone), between spiritualist “Abstraction” and an immanent “Constructivism,” there is an ambivalence which may constitute a third tendency: to choose both tendencies, and in so choosing to put them into utmost tension with each other. An oscillation pattern we may write to infinity: to heal to overwhelm to not heal…

Considering the ethics of this second tendency – to present directly beyond ponderability, or comprehension: where to pre-hend, or grasp in advance of feeling, would be to violate the responsibility of voiding one’s gaze, witnessing beyond witness or looking awry — it is crucial the extent to which many of Hirschhorn’s Afghani and Iraqi figures are disfigured; that is, lacking faces as portals of commandment and absolute obligation. Instead, what may remain of obligation is a transcendental lack-in-excess, the excessive (non-)presences of photographed corpses striking-out an all-too-human economy of legal-moral retribution. Not only in the images of mutilation, but in the sheer volume of blown-up headlines embodying a thick fog of media warfare, the viewer is caught in the throes of a type of negative transcendence: a failure to transcend, to sublate or synthesize, a series of messages in excess of what they would say — noisy in their contradiction, tragically enjoyable in their paratactical (non-)sense-making. Between sublimation and a transcendent negativity, “Chromatic Fire” and “Concrete Shock” (the names of two of Hirschhorn’s three rooms at Gladstone), between spiritualist “Abstraction” and an immanent “Constructivism,” there is an ambivalence which may constitute a third tendency: to choose both tendencies, and in so choosing to put them into utmost tension with each other. An oscillation pattern we may write to infinity: to heal to overwhelm to not heal…

If there is any problem I have with claiming Hirschhorn for “critical theory,” as many critics have done productively and which much of the contemporary art world resists for its own reasons, it is that he is a devotional artist; an artist devoted to divine presence through a highly unique, and recent, form of materialism. This devoted materialism – a materialism as much after Mondrian, Malevitch and other Abstractionists as it is the philosophers Hannah Arendt, Georges Bataille, Gilles Deleuze and Baruch Spinoza – would maintain the radical freedom of the artist as a noble actor within collective cultural struggle (“The decision to be an artist is the decision to be free. Freedom is the condition of responsibility”), while simultaneously realizing the suspension of this very freedom in the depersonalization of Abstraction for itself.

If there is any problem I have with claiming Hirschhorn for “critical theory,” as many critics have done productively and which much of the contemporary art world resists for its own reasons, it is that he is a devotional artist; an artist devoted to divine presence through a highly unique, and recent, form of materialism. This devoted materialism – a materialism as much after Mondrian, Malevitch and other Abstractionists as it is the philosophers Hannah Arendt, Georges Bataille, Gilles Deleuze and Baruch Spinoza – would maintain the radical freedom of the artist as a noble actor within collective cultural struggle (“The decision to be an artist is the decision to be free. Freedom is the condition of responsibility”), while simultaneously realizing the suspension of this very freedom in the depersonalization of Abstraction for itself.

By a chiasmus of these two positions: radical agency and transcendental depersonalization, I wonder if we can not locate a radical position towards violence, one that has been opened up by the recent publications of Giorgio Agamben, in which the philosopher discusses what he calls “states of exception.” Particularly relevant to Hirschhorn’s recent work is Agamben’s reading of the debates between Carl Schmitt and Walter Benjamin concerning the “state of exception” in Germany during the first World War. If, as Agamben shows after Benjamin, states of exception are exceptions that historically ground the rule of democratic and totalitarian states alike then one should look elsewhere, in states beyond states of exception, to recover that which remains beyond the rule of both natural and cultural law: beyond “bare life” (Agamben) and “mere life” (Benjamin): the reduction of bodies to biological states of subsistence in the suspension of legal conventions grounded by constitutional law and international agreements regarding human rights.

For Benjamin, this state beyond states of exception is achieved by two means: by passionate acts constitutive of “pure means,” or means no longer directed towards a juridical or moral result, an unpurposeful means; and in “divine violence” that is “law-destroying,” that in its anarchism interrupts law as a source of juridical retribution and as the fulfillment of mythical fates. “This very task of destruction poses again, in the last resort, the question of a pure immediate violence that might be able to call a halt to mythical violence. Just as in all spheres God opposes myth, mythical violence is confronted by the divine. And the latter constitutes its antithesis in all respects. If mythical violence is lawmaking, divine violence is law-destroying; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them; if mythical violence brings at once guilt and retribution, divine power only expiates; if the former threatens, the latter strikes; if the former is bloody, the latter is lethal without spilling blood.”(“Critique of Violence”)

For Benjamin, this state beyond states of exception is achieved by two means: by passionate acts constitutive of “pure means,” or means no longer directed towards a juridical or moral result, an unpurposeful means; and in “divine violence” that is “law-destroying,” that in its anarchism interrupts law as a source of juridical retribution and as the fulfillment of mythical fates. “This very task of destruction poses again, in the last resort, the question of a pure immediate violence that might be able to call a halt to mythical violence. Just as in all spheres God opposes myth, mythical violence is confronted by the divine. And the latter constitutes its antithesis in all respects. If mythical violence is lawmaking, divine violence is law-destroying; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them; if mythical violence brings at once guilt and retribution, divine power only expiates; if the former threatens, the latter strikes; if the former is bloody, the latter is lethal without spilling blood.”(“Critique of Violence”)

I believe the punches SE packs to be ones “lethal without spilling blood” insofar as they put its audience face-to-(de)face(d) with divinity as presented by creative force and aesthetic determination. If these creative forces bear-out their effects directly in the printouts and Xeroxes of mutilated bodies and the confusion of headlines (often literally) ripped from the contexts of various Western media sources, these forces may have a symbolic effect through their correspondence of contemporary mannequins and tribal African sculptures both riddled with nails. While the first force puts the audience in the presence of the “unpresentable” (Lyotard) and the “there is” (Levinas), the second, symbolic one indicates a post-mythical function of art itself: to substitute a creative violence of works of art for a violence of territorialization and retributive warfare. This later violence, the violence of true Holy War beyond “fundamentalism” and cynical “secularism” alike, of divinity beyond mythos, is that which may trump the reduction of bodies to “mere life” and “bare life” the stakes of which we see playing out currently in Guantanamo and elsewhere. It is the violence, lastly, of sacrificial expiations, a pure immediate violence Benjamin’s contemporary, Georges Bataille, recognized as the very opposite of territorial warfare in its glorious wages, its infinite use values and malicious possessiveness: “In deadly battles, in massacres and pillages, it has meaning akin to that of festivals, in that the enemy is not treated as a thing. But war is not limited to these explosive forces and, within these very limits, it is not a slow action as sacrifice is, conducted with a view to a return to lost intimacy. It is a disorderly eruption whose external direction robs the warrior of the intimacy he attains. And if it is true that warfare tends in its own way to dissolve the individual through a negative wagering of the value of his own life, it cannot help but enhance his value in the course of time by making the surviving individual the beneficiary of the wager.”(Theory of Religion)

I believe the punches SE packs to be ones “lethal without spilling blood” insofar as they put its audience face-to-(de)face(d) with divinity as presented by creative force and aesthetic determination. If these creative forces bear-out their effects directly in the printouts and Xeroxes of mutilated bodies and the confusion of headlines (often literally) ripped from the contexts of various Western media sources, these forces may have a symbolic effect through their correspondence of contemporary mannequins and tribal African sculptures both riddled with nails. While the first force puts the audience in the presence of the “unpresentable” (Lyotard) and the “there is” (Levinas), the second, symbolic one indicates a post-mythical function of art itself: to substitute a creative violence of works of art for a violence of territorialization and retributive warfare. This later violence, the violence of true Holy War beyond “fundamentalism” and cynical “secularism” alike, of divinity beyond mythos, is that which may trump the reduction of bodies to “mere life” and “bare life” the stakes of which we see playing out currently in Guantanamo and elsewhere. It is the violence, lastly, of sacrificial expiations, a pure immediate violence Benjamin’s contemporary, Georges Bataille, recognized as the very opposite of territorial warfare in its glorious wages, its infinite use values and malicious possessiveness: “In deadly battles, in massacres and pillages, it has meaning akin to that of festivals, in that the enemy is not treated as a thing. But war is not limited to these explosive forces and, within these very limits, it is not a slow action as sacrifice is, conducted with a view to a return to lost intimacy. It is a disorderly eruption whose external direction robs the warrior of the intimacy he attains. And if it is true that warfare tends in its own way to dissolve the individual through a negative wagering of the value of his own life, it cannot help but enhance his value in the course of time by making the surviving individual the beneficiary of the wager.”(Theory of Religion)

Against the wages of Iraq and elsewhere and the neo-colonial ravaging of the United States and its allies, Thomas Hirschhorn has waged his own battle: a battle that should not result in loss of “mere life,” and that if it has anything to gain, may gain “sovereign violence” (Benjamin) once again through the sacrifices of profaned creation.