Cut a Hole Through Chipotle: An Interview with Ross Gay and Richard Wehrenberg

06.08.15

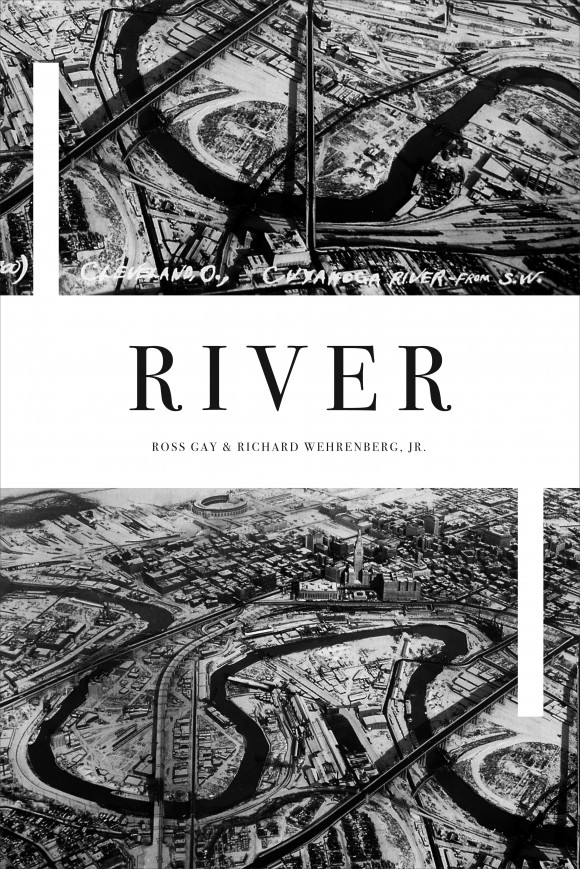

River came out last fall from Monster House Press, a midwestern publisher/collective, and the cover is an aerial photograph of the Cuyahoga River, which flows southward from Lake Erie through Cleveland down and around to small cities likes Akron and Kent. The river looks like a diseased artery running through a body that no longer gets fresh air. Of course, the photo being dated from the 1970s, this last sentence really isn’t even really metaphorical, as at the time the river would routinely set ablaze due to the industry and population that were polluting and endangering the river and its surrounding ecosystem.

This chapbook by Ross Gay and Richard Wehrenberg defies categorization. I don’t think I’ve ever read anything like it. It is part poetry, part essays, part sketchbook, part atlas, part pure reflection, pure collaboration, seamlessly weaving, in a fun but serious way, a million years of history together through these two authors’ minds. The mini-essays and epigraphs and drawings therein are beautiful and bold, although also brief and just, I felt after I had finishd, too short. I wanted more of the deadpan descriptions of Indian mascots riding out on horses over a field once ruled by an indigenous tribe. I wanted the dry observations seen in the descriptions of a town like Bloomington or Kent. Sometimes you have to learn to savor what you can get, though. The book itself seems like a meditation on preservation, mutalism, and temperance.

I asked them both questions and they responded with much better answers.

What made you guys first want to write?

Ross Gay: I think I probably wrote a little love poem here and there in high school, but maybe two of those. And I liked to write silly parody things around that time too—so if we were (no, we were) supposed to write a little report on the Steinbeck novel I can’t remember the name of, the dust bowl novel, you know it, and I wrote this deeply stupid little parody, probably offensive in every way. Or me and my buddy Jay would exchange our journals in class and write these verbal onslaughts about the other person, drawing pictures and everything. I wasn’t calling it creative writing, though that’s what I was doing. (Grapes of Wrath!)

Richard Wehrenberg: My own feelings of depression, anxiety, loneliness, idiocy, confusion, boredom, et al. Realizing the pain you sow, intentionally or not. Desiring to find a way out of those feelings & actualities. Not wanting to feel trapped in certain thought processes / identities / ways of seeing. It seemed the only “real” way I could engage with the world was by writing. It helped rive mundanity / inanity—split it open like a fish—and inside was more of the same shit of life, but also: beauty, simplicity, joy, calm, peace.

Ross Gay

Did you self-publish your initial writing?

Gay: Self-published my first stuff, which was when, one Halloween-time, my buddy Mike and I stole a bunch of pumpkins from people’s front steps and carved them up really pretty, turned them into jack-o-lanterns, and carved our name, “Halloween Saints,” into the back of them, before returning them. Seriously! Mike’s brother Bill surely followed us doing our sweet little deed and pissed in the things or smashed them against the recipient’s door and took off in his big floppy Reebok high tops with the tongue pulled way out over his jeans.

Wehrenberg: I took quickly to zines and chapbooks and DIY and all that and did that / still do. It feels natural to me to make an object, any object, and share it, without concern for / consciousness of standardized / normalized practices. To make [object] and walk it over to someone else nearby and say “Hey, what do you think?” or “Check this out.” The first time I got published by someone else it felt good, of course, but did make me feel like I needed to do that solely. I view both as ways of communicating / sharing among many other ways.

We are in some moment in history that feels like everything has been set up in such a way and will be around like this forever—major publishers and anthologies and corporations and wikipedia articles and record labels, et al.—and I really just don’t feel that permanence, that ostensible power and pull of large entities like that. It’s hard to imagine the world differently than in what we are embedded, but I don’t think this is how it works objectively. I know it’s not. Do what you do and don’t let convention cage you. Art will go where it will go, magically, almost without effort. I find I focus on writing / art to share in moments—at readings, in emails, in conversation, with myself and others—meaningfully here with other bodies alive in the same moments now. Writing like everything: breathing, walking, pooping, sleeping. I don’t require much outside affirmation. I am small scale. I find celebretizing undesirable.

Were there any models you used as inspiration for River?

Gay: I love Rebecca Solnit’s Atlases, and I was and am thinking about those things.

Wehrenberg: We were interested in buried things. Swept under the rug things. That the Jordan River runs underground through most of Bloomington influenced the structure / model. Footnotes seemed to embody, textually, that theme, so we used those a bit in design. You could say we used this literal physical place as a model. Also: the ideological structure & practices of this current moment in history as reflected via things like erasure act as guides for the shape and course of the book.

Is the Jordan River something one would probably notice if they weren’t on the campus of Indiana University?

Gay: Never, unless you cut a hole through Chipotle and whatever’s beneath it to get to it, chuggling on by. Never. And when you see it coming out of a drainage ditch just southwest of downtown you wouldn’t really think of it as a river. You might think of it as storm run-off or something.

Wehrenberg: I don’t think so. They’d be like “what’s that ugly drain ditch thing?” if they saw it off-campus. Also, it’s underground for a few miles under downtown, so you can’t even see it. You have to go south of downtown a little ways to find where the culvert empties and the drain ditch-creek amalgam appears. People would not even think of the word river. I did not know it was a river until I learned there was this thing called The Jordan River. It’s more of a creek, but I admire their embellishment.

I live in New York. Here the literary scenes or worlds are essentially infinite and a lot of times not really fun at all. How is it like in Bloomington?

Gay: It’s wonderful. There are lots of good readings and very good writers. I think of it as delightful, and intense in how good and serious the scene is. I was recently at a slam in a bar here and there were 200 people there. And I’ve been at these beautiful, intense readings in houses, etc. It’s the shit.

Wehrenberg: Bloomington is a a small town, or pretends to be a small town. (Indiana University has a population of ~45,000 students. piled on top of the rest of the townies who hit about 40,000.) It’s in the Midwest which naturally has this tendency toward low key aspiration / interaction. The scene / world here seems to include, just like, whoever is interested and able, in my opinion. I think because we are not as spread out physically and culturally as NYC, it’s easier to have a more community feeling reading and participation here. People don’t feel as in competition with each other here as I have felt NYC to feel. When I moved to Bloomington from Columbus, Ohio, I started setting up readings and things have seemed to be steadily growing, from my perspective, not just because of me obviously. I believe people crave things like readings, especially when it is relatable and accessible and challenging. It reminds me of AA; people finally just hearing words they might need to hear, saying what they need to say, instead of just useless refrains of “How’s it going?” and “Good.” I don’t know—everything seems just closely connected here in all realms. Maybe that’s just me though. I prefer a chill relation. No games. How about we’re alive and that’s hard enough as a mantra?

Richard Wehrenberg

What were your childhoods/adolescences like in the Midwest?

Gay: Oh, you know, like some kids’ childhoods. I feel like in some ways I had the best childhood ever—I had and still have a brother I loved (even though we fought all the time), and because we didn’t have lots of money, we got to sleep in the same bed until I was probably 13 years old or something. And we lived in an apartment complex with 508 apartments jammed together, so we were always close to our friends, could almost always find a game of basketball or street hockey to play, pausing time to time to let the cars go by. We also lived right next to a woods, which shows up in River, which we spent a lot of time in. There was a creek, and a culvert, and more. Skunk cabbage galore. It was a magical space that still shows up in my dreams. I had dear parents who tried their best and loved us a lot.

Wehrenberg: I was raised by older parents (my mother birthed me at age 42) in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio very close to the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. I mention my mother being older because I think I perceive that fact as being relatively distinct from most families, and it thus making me distinct, though I couldn’t expound on how. I mention the park because the “natural world,” its silences and harmonized chaoses, the river, shaped me in countless ways. Cleveland holds loads of humility, which took shape in my being. I grew up with a sister and brother close to my own age whom I loved and did things with. My parents loved us, though I recall their lack sometimes more often than their presence. My dad owned his own remodeling business; my mom sold Toyotas, then Hondas. II was a will-less, shy child. I didn’t want life, a life that was “mine.” I wanted to be invisible really bad. I didn’t understand why this reality was the one I was born into.

Do you think the right geographic and cultural environment can make a person or people happy?

Wehrenberg: Cultivating your brain / thoughts to be healthier, feeling / freeing your language and individuality while also connecting it with a larger universe is the only “true” way I can see to do that. But it depends, you know, on what happy means or how it is used. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Axiom 1: “People are different from each other. It is astonishing how few respectable conceptual tools we have for dealing with this self-evident fact.” It’s in you, I want to say. Of course, we all thrive in different environments, so maybe as part of the brain / thought thing, understanding what climate would be most beneficial to your “happiness” or “healthiness” or whatever part of it. I like to think I could live anywhere, because I already live in my head every day and feel pretty good with that head. I can’t live underwater or in space, though I would enjoy that. You are always with you, wherever you go, and that you is always changing, so it’s complex. Of course, not everyone can just move wherever, or cultivate their heads healthfully, or even think about this, or want any of this.

——————–

River is available now from Monster House Press.