Coolness, Class, and the Canon: Blue Velvet vs. Something Wild

03.09.15

Released within a month of each other in the fall of 1986, Blue Velvet (dir. David Lynch) and Something Wild (dir. Jonathan Demme) have so much in common it’s like they emerged simultaneously from the collective unconscious. Both films share the same premise: a young man discovers a world he didn’t know existed, lured there by a woman into S&M who’s involved with a dangerous criminal from the wrong side of the tracks, and who the young man must kill in order to save himself.

Both protagonists experience an unsettling tragedy in their personal lives at the beginning of the movie. For Jeffrey, it’s his dying father. For Charlie, it’s his dissolving marriage. And both films insist that normal life is a sham, a comforting lie we tell ourselves in the hope that all the scary things in the world won’t be able to hurt us.

There’s even more similarities. Both directors had previous feature films (Dune for DL, Swing Shift for JD) that were commercial & artistic failures. The movies had been recut without their permission, and both directors responded by simplifying their working process, going smaller—shooting on location, embracing their outsider status—and ensuring they would have final cut.

Both movies’ plots are labyrinthian and convoluted, and a full synopsis of either would easily double the length of this article, but here’s some necessary exposition:

Blue Velvet – Jeffrey (played by Kyle MacLachlan) returns home after his dad’s had a stroke. Walking through a field, he finds a severed ear and brings it to a police detective, who has a teenage daughter Sandy (Laura Dern). She tells Jeffrey that a woman named Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) might be involved. So Jeffrey decides to do a little investigating and sneaks into her apartment. Dorothy comes home, undresses, catches him hiding in the closet, pulls a knife on him, and is about to perform fellatio on Jeffrey (cause she’s weird, man) when Frank (Dennis Hopper) shows up. She shoves Jeffrey in the closet. Frank enters and, inspired by an abundance of nitrous oxide & freudian theory, has (profane, non-traditional) sex with Dorothy while Jeffrey watches from the closet. Adventure ensues.

Something Wild – Charlie (Jeff Daniels) is your basic tight-assed financial district yuppie with a wife and two kids. One afternoon he does the old dine-and-dash from an NYC sandwich place but Lulu (Melanie Griffith) chases him out the door—she doesn’t work there, it’s just for kicks—and confronts him. She sizes him up as a closet rebel and after giving him a hard time offers him a ride back to work, whereupon she (very sweetly) takes him through the Holland Tunnel into New Jersey, robs a liquor store, brings him to a motel, handcuffs him to a bed and has her way with him—most of this happens against Charlie’s mild protests. Adventure ensues.

And oh yeah, I guess both movies also have an uncomfortable fellatio scene, though with extremely different levels of discomfort. It should also be noted that every actor/actress gives the best performance of his/her career.

There’s more. Both films were critically acclaimed at the time. Both have been issued on DVD as part of The Criterion Collection. Bret Easton Ellis tweeted a little while back, “The two key American films of the 1980s: ‘Blue Velvet,’ ‘Something Wild’…” And yet only one of these films is considered a bona fide classic—BV appears in pretty much any Top 100 Films Of All Time list you can find—while SW is more or less an afterthought these days. Which is a goddamn shame. Because after going back and watching both movies obsessively over the past couple of weeks, I’ve fallen completely in love with SW, while developing this weird contempt for BV that I never had before. And in spite of all their many similarities, I’ve realized that these two movies couldn’t be any more different.

One last coincidence: they’re both currently streaming on Netflix.

———–

Don’t get me wrong. It’s understandable why the two movies have different legacies. DL went on to do Twin Peaks, which completely captured the public’s imagination (until he made Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, which foregrounded the incest storyline and repulsed most viewers and critics—me, I think it’s pretty great). BV easily fits beside the rest of DL’s work. You say the word ‘Lynchian’ and most people know (or think they know) exactly what you mean. But Demme’s films are so different from one another that an adjective like ‘Demme-esque’ would be meaningless. Every one of DL’s films (with the exception of The Straight Story) has reinforced his brand—to oversimplify, a type of American Surrealism that is both quirky & horrifying. Married to the Mob is the only thing in JD’s filmography that’s even remotely close to SW’s sensibility. And while JD went on to have greater success in terms of box office & Academy Awards (Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia), his other films have little of SW’s coolness (though SotL does feature a Fall song during its harrowing climax, and one from Hex Enduction Hour no less—that misanthropic band’s most misanthropic album).

Or to put it another way, DL carries way more social capital among the artist set than JD probably ever will. Lynch is someone you ‘get into.’ He’s a director people name drop to try and make an impression. Despite filming one of the best concert movies of all time in Stop Making Sense, JD’s style in that film is unobtrusive enough that even as that band’s cool factor has increased in the last few years, JD’s still probably best known today, if known at all, as The Silence of the Lambs guy.

———–

While the two movies share the same subject matter, their approaches are completely different. SW has moments that are every bit as frightening and violent as BV, but it’s buoyed by a lightness & excitement—a genuine love for its characters—that’s totally missing in BV. Which raises an interesting question: can a movie be fun and still be avant-garde? Can light be more interesting than dark? We have a tendency to overrate coldness and devalue the optimistic, but SW burns with such an intense joyous heat, and still flashes all kinds of artistic pyrotechnics, that it’s hard to dismiss. SW is all too aware of the darkness in the world; it isn’t naive in the least. But it feels real to me in a way that BV’s doesn’t. And it comes to terms with its darkness in a mature way that BV doesn’t even attempt.

Because for all its transgressiveness, it turns out that BV is, at its heart a fearful movie. It’s afraid of life. Both movies’ protagonists are, in Jeffrey’s words, ‘seeing something that was always hidden,’ but where Charlie finds freedom and spiritual growth in his journey, Jeffrey finds things so terrible that he flees back to normalcy. SW sees anarchy as a source of liberation, but to Lynch it’s a horror show. So who’s the real rebel here? The genuine avant-gardist?

The consensus says that BV is about the corruptness beneath the surface of small-town life, but if anything it’s about seduction—Jeffrey by Dorothy, Sandy by Jeffrey—and the biggest seduction is the one DL performs on the viewer. BV is awash in sensual imagery: the way he photographs curtains, the way he lights the trees at night, the hellish shade of red we see on the walls of Dorothy’s apartment. It’s libidinous and breathtaking and soft and pungent and it can’t help but take your breath away. It adds a dimension to BV that, for all its hyperactive camera love, just isn’t there in SW. Demme’s movie is too excited, has too much story to tell, too many people to see, for the camera to function the way Lynch’s does.

And BV’s first few minutes—the opening scene remains one of the most aesthetically-thrilling moments in film history—are so complete & perfect that it carries you through the rest of the movie ready to overlook anything…

…like how for a movie set in 1986, BV at times feels almost like a period piece. Most of its dialogue is downright corny. Sandy/Jeffrey resemble the teenagers from Happy Days more than they resemble the teenagers in, say, The Breakfast Club. Which may be intentional on Lynch’s part, but while BV gets credited for its irony & satire, the only thing being satirized is 50s middle-american values, something that barely existed in 1986 and had been getting skewered for nearly 20 years. And as satire goes, BV’s a lot closer to The Addams Family than Lenny Bruce.

SW, on the other hand, feels firmly rooted in the abundance of Everything That’s Happening Right Now (1986 version of Now). Comparatively, BV feels wooden & stiff where SW swings. It feels breathing and alive even in its darkest moments, and its characters are more fully rounded. Most of BV’s characters are presented as sets of opposites—dark Dorothy vs. light Sandy, corrupt cop vs. honest cop, Jeffrey v. Frank—but SW synthesizes its characters’ fragments into a coherent whole.

Just look at the female characters. You have Melanie Griffith’s Lulu overflowing with life vs. Isabella Rossellini’s Dorothy overflowing with death. Lulu wants to liberate Charlie, to lift him out of his tedious existence. Dorothy drags Jeremy down into her spiritual abyss. Where women are into S&M, Lulu handcuffs Charlie while Dorothy is dominated by Frank. And if their relationship hints at being consensual—Dorothy reveals herself to be nearly as kinky as Frank—she’s so thoroughly degraded near the end of the movie that the hypothesis crumbles. And in the very last scene, after Frank has been killed—the agent of chaos eliminated—and everything’s returned to normal, we see her softlit & smiling, impeccably dressed, while her son, wearing a goddamn beanie with a propellor on top like this really is the 1950s, runs towards her in slow motion for a maternal embrace. Lynch presents her happiness as so complete and total that it obliterates any argument that the arrangement with Frank was ever satisfying, let alone truly consensual.

Even in a society with a serious virgin-whore complex, BV’s is especially problematic. Lynch would later do the blonde high school angel vs. dark-haired lady of the night way better in Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks because he would depict the multiplicities of personae contained within each person (Betty contains elements of Rita and vice versa, while Laura Palmer is both at once). They both come across a lot truer than the women in BV, where the split is so brutally extreme and unrealistic. Lulu synthesizes BV’s schizoid femininity into a coherent whole. Even when Lulu later reveals herself as Audrey—her hair transformed from a dark Louise Brooks-style bob into a spiky blonde—she still remains the same person.

Lynch seems unable, at this point in his career, to create characters who don’t exist purely for their symbolic value. Even his protagonist feels affected. Sandy says she can’t tell whether Jeffrey ‘is a detective or a pervert,’ but Charlie—in his handcuffs, in the way he rescues Audrey from Ray—is emphatically both. Interestingly, while people love to quote Sandy’s line, no one ever includes Jeffrey’s inane response, ‘That’s for me to know and you to find out,’ sounding more like he’s in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure than a surrealist nightmare.

Jeffrey isn’t able to reconcile the different aspects of his personality—the part that craves safety & the part that craves excitement. The instant he experiences real danger, he retreats back into the safety of the life and values he had before he ventured into Dorothy’s apartment. The night after his adventure with Frank that nearly gets him killed, he breaks down in front of Sandy and sobs, ‘Why are there people like Frank? Why is there so much trouble in the world?’ Which is pretty rich coming from a guy who’s been slapping around an abused woman so she’d let him fuck her. Compare this to Charlie who, given the opportunity to flee danger, rushes back into it in order to save Audrey. And then, having dispatched with Ray at the end of the movie, decides to quit his job and embrace a life of uncertainty because he doesn’t want to give up his new found feelings of freedom. Jeffrey says early on in BV, ‘There are opportunities in life for gaining knowledge and experience. Sometimes it’s necessary to take a risk.’ But Jeffrey recoils at the knowledge & experience he gains and scurries back to the safe & familiar, while Charlie—in spite of the very real danger & loss of innocence he’s also experienced—is still willing to take risks.

———–

It’s interesting to note that while BV’s characters are starkly drawn types, completely separate from each other, the movie’s tone remain consistent. SW is the opposite. Its characters are consistent, but the plot is schizophrenic. The second half of the movie is significantly darker, more menacing & violent, less screwball than the first half. Even the soundtrack shifts from lighter reggae & afrobeat to guitar-driven rock. In fact, the two parts are so distinct that you can literally see the movie get darker. Just watch at the 2:45 mark:

And at the end of the clip, SW’s villain swings into view. It’s almost two separate movies: Boy Meets Girl, and Boy Meets Ray (a lot of critics at the time had a problem with this, feeling they needed to prefer one half over the other and qualified their praise for the movie).

And yes, that was The Feelies you just saw. Both directors were so completely in love with music that their movies are dominated by their soundtracks. But again, Lynch’s love seems narrowly obsessive where Demme’s is sprawling & hyper-engaged with then-current cultural coolness (New Order/Go-Betweens/X) in a way that Lynch’s (Bobby Vinton/Roy Orbison) is not. Forty-nine songs appear in SW, and that’s not counting the orchestral score (done by John Cale & Laurie Anderson). BV has four non-score songs, and the one that isn’t from the 1950s sounds like it might as well be.

Again, just note the way that SW is excited and overflowing with life. There’s even a way that Demme frames the people in his movie (and there are dozens of minor characters) that makes you want to like them. A friend of mine just watched the movie for the first time and said her favorite character was Peggy, the pregnant wife of Charlie’s co-worker we see at the reunion. Peggy has maybe six lines of dialogue and is only in the movie for just a few minutes, but Brigette just now screamed out with joy when I told her that the actress had been the singer in Suburban Lawns.

So I guess what I’m trying to say is that Jonathan Demme has a cool factor of his own. One that, for this particular movie at least, gives David Lynch’s brand of cool a serious run for its money.

But let’s go back and talk about Ray. One of the reasons why SW’s halves feel so different is because Ray Liotta dominates the movie whenever he’s onscreen and he doesn’t show up until halfway through. He’s terrifying in a way that BV’s Frank, for all his violent freakery, never quite manages to be. And that’s probably because I’ve actually known people like Ray. I’ve never met anyone like Frank. Which again emphasizes the realness, the possibility-ness of SW against the surreal, dreamlike state of BV. Frank feels like a cartoon. An interesting cartoon, but two-dimensional nonetheless. Along with his violent streak, Ray also has a sweetness to him—he just wants things to go back to the way they were before he went to jail, with him and Audrey robbing stores and running around having a good time. He’s motivated by his inability to let go of the past. We have no idea what Frank’s motivations are.

Ray’s able to be charming in a way that’s beyond the plodding Frank. When Ray makes a crude remark to Charlie about sex with Audrey, Charlie flinches and tells him sternly that there’s no need for that kind of talk. After thinking for a few seconds, Ray apologizes with what feels like genuine sincerity. He’s not a malicious sociopath. He feels genuinely betrayed, and not just because Audrey’s found someone else while he’s been serving time for a crime that Audrey was probably involved in, but because the someone in question looks like all the things Ray isn’t—rich, clean, and dorky. He genuinely believes an injustice has taken place, and any minute now everyone will see things his way and come to their senses.

Don’t get me wrong. Ray’s anger is genuinely scary, and more than a little unhinged, but it’s so rooted in underclass rage that it’s hard not to feel a little sympathetic for him. And it’s that understanding from the audience that gives Ray outbursts an extra kick. You feel for him. You want to try and reason with him. Because we get to see the good parts of Ray—and a big part of this is due to the brilliance of Liotta’s performance—it hurts that much more when we see the bad parts.

———–

Issues like class and race don’t exist in BV, at least as ideas to be considered, and keep in mind that the absence of politics is itself political, but at its worst, BV peddles a waxy nostalgia that is eerily similar to the same Morning In America crap being spouted by the recently re-elected Ronald Reagan. And again, we can say that BV’s nostalgia is subversive, but that theory just seems like projection on the part of critics and fans. By any objective reading, the film is resolutely conservative in the way it deals with class, race, and women. Even its ending is conservative.

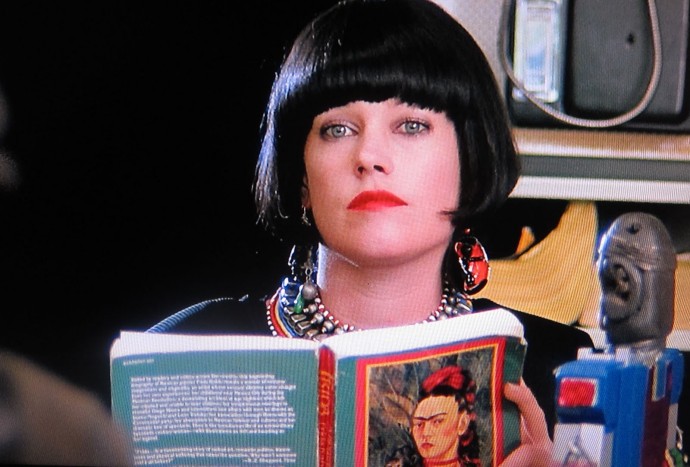

Especially compared to SW, which is a riot of multiculturalism. Its soundtrack and screen are filled with different races, and the lead characters interact easily and naturally with the different people they meet (which mirrors the onscreen relationships in Stop Making Sense, incidentally). In her most Lulu moments—that is to say, when she’s acting as a liberating force—we see Audrey reading books about Frida Kahlo and Winnie Mandela, her jewelry/decor awash in African colors & design. BV has only two black characters. They both work for Jeffrey’s father at his hardware store, and are one ‘massa’ away from being a broad enough caricature to be considered offensive.

And then there’s Frank. who’s literally from the wrong side of the tracks, and curses like a sailor suffering from Tourette’s—Fuck you, you fucking fuck!—drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon (long before its hipster appropriation), while Jeffrey prefers Heineken and doesn’t curse once in the entire movie. You get the impression that Lynch sees the underclass as something to be feared: vulgar and unrefined, lacking in self-control, and with no fixed ethics or morality. Again, this lines up perfectly with the conservative values of its era. I mean, the movie’s plot boils down to: rich white kid comes home from college, slums it up with the poor and gets his vicarious kicks until he realizes he’s in over his head, then returns to the safety & privilege of his normal life completely unscathed, having lost absolutely nothing in the process—you’d think a woman showing up at your girlfriend’s parents’ house completely naked and saying, ‘He put his disease in me’ over & over might screw up your chances with her, to say nothing of her parents’ opinion of you, but not for old Jeffrey. Even his dad gets healthy at the end. No wonder liberal arts majors love it so much.

And don’t forget about that virgin/whore complex. The virginal Sandy is always a good girl framed in light; Dorothy is presented in darkness & despair until she reunites with her son, reinforcing the essentially conservative message that a woman is only worth our respect if she becomes a good mother, nurturing and sexless. BV isn’t a political movie, but the politics that come through are ugly & rancid.

For all its reputed commentary on small-town America, SW feels engaged with the country in a way that BV doesn’t. By 1986, the counterculture of the 60s/70s seemed well and truly dead and SW feels at times like a desperate attempt to bring it back to life, both by depicting the joy in transgressions that were out of fashion at the time (hitchhiking, drinking and driving, the recurring use of the song ‘Wild Thing’) and by digging deeply into more current rebellions (rap, reggae, underground rock). Released at the height of 80s values—yuppies, greed, shiny surfaces, empty patriotism & orgiastic consumption—the movie’s a clear statement against all of those things.

At times, the movie feels like a referendum on America—both love letter and indictment. JD seems genuinely fascinated by the US. Shots linger on the highway scenery, the churches, the people, longer than you’d expect. Ten years on from the bicentennial, Audrey’s reunion swells with American flags. Demme is willing to wrestle with America in a way that Lynch is not. By acting as if there were something at stake in the nation’s future, it taps into a genuinely rebellious attitude.

———–

In the early stages of this essay, I wrote in my notebook, ‘don’t put down Lynch to pull up Demme,’ but the longer I work on this the more I’m starting to detest a film that I previously thought I loved. I find myself asking questions like: is Blue Velvet’s only redeeming quality the beauty of its camerawork?’ ‘Is its examination of darkness so overly simplistic that it doesn’t really examine anything?’ ‘Can a film with a clunky plot, stilted dialogue and wooden acting truly be considered a masterpiece?’ ‘Does the majesty of the opening scene—everything up to and including the insects writhing beneath the lawn—say everything the movie has to say in five minutes and says it better than the 115 minutes that follow?’

BV’s been faulted for being sick & depraved, but to me it makes more sense to call it reductive and trite. There’s a smugness at the heart of BV, an icy distance that is the antithesis of SW’s heat. Ultimately, SW is about the jeopardy in living a completely normal life—you’ll miss out on the excitement of being alive. It doesn’t back away from the fact that every adventure carries the potential for danger, but it asserts that’s a price worth paying because the only alternative is the forfeiture of one’s soul.

BV on the other hand is a cautionary tale about the danger in taking risks. Despite Jeffrey’s initial excitement at discovering ‘what’s always been hidden,’ the rest of the movie seems to say be careful what you wish for, kid, and by the end of the movie he’s relieved and grateful to be back in his normal suburban home.

Or to put it more simply SW is a story about liberating the repressed. In Jeffrey’s tearful return to normalcy, BV values repressing the liberated. One movie feels alive; the other feels stunted somehow. And I have to believe that a movie that says ‘the world is filled with all kinds of unimaginable magic every goddamn day so go out and find it’s more interesting, more subversive, and more genuinely cool, than a movie that says the opposite.

Look, I still enjoy David Lynch movies and I still appreciate BV—which conjures up pure sensual mood in a way that SW can’t begin to touch—but watching these two films together reveals limitations and deficiencies in BV that I’d never noticed before. And when I compare it to SW, the idea that it doesn’t exist on a list of the Best Films of the 80s, or in queue on everyone’s portable device, seems like a goddamn travesty.

Because any canon that doesn’t include both of these films is an incomplete canon. And more importantly, any life that doesn’t include both of these films is an incomplete life.