Concerning the Work of Dark Red Paw

28.10.06

Concerning the Work of Dark Red Paw

Concerning the Work of Dark Red Paw

from the novel The Dizzies

by Ed Park (illustrations also by the author)

A week before the engagement notice appeared, I took my beloved, Mercy Pang, to a party at Dora Travertine, the gallery where I worked as both assistant and janitor. Some months I was more the latter than the former. It was not where I wanted to be at that stage of my life, but these things don’t change overnight, I reminded myself. I was even beginning to think that these things sometimes never changed at all.

That Friday was the opening-night fiesta for the career retrospective of Dark Red Paw, the Native American artist. Lately he had given off a light stench of demimonde scandal—his ex, a sculptress named Ida McNut, had told an interviewer that DRP’s heritage was not even remotely American Indian, but largely Portuguese, diluted with a little Russian. People showed up, curious whether Paw would take the high road, or else get very drunk and start throwing hors-d’oeuvres, which he’d done at Ida’s “Six Chromatic Nudes” show two months prior. A flung glass of wine had marred a polystyrene obelisk entitled Strife II but surprisingly the stain had increased its value. That was the year everyone wanted to get their hands on someone else’s grief.

I filled Mercy in on the scuttlebutt. She had never seen any Dark Red Paw, perhaps understandable, as his star had been in decline for years. I still believed he was capable of interesting work. I had thought that if I ever went to graduate school—one of myriad vapory plans at this stage of my life—I might study him. I might write the definitive monograph on Dark Red Paw. Sure. Anything was possible. I might also become president of the United States and a professional wrestler and get voted World’s Handsomest Man.

My favorite Paw piece was from what was confidently called his middle period, which lasted for decades and had just concluded two years prior. The piece claimed to reproduce in toto the forbidden name of a fearsome Hawaiian goddess. The name was 40,000 letters long. He wrote it out across one wall with a black fountain pen in a meticulous sloped hand. It was grueling work, though actually he had some help after the first fifty letters—a team of inner-city interns known as the Paw Patrol.

My favorite Paw piece was from what was confidently called his middle period, which lasted for decades and had just concluded two years prior. The piece claimed to reproduce in toto the forbidden name of a fearsome Hawaiian goddess. The name was 40,000 letters long. He wrote it out across one wall with a black fountain pen in a meticulous sloped hand. It was grueling work, though actually he had some help after the first fifty letters—a team of inner-city interns known as the Paw Patrol.

The characters were dime-sized. Every so often one would be written in red, suggesting that some code was involved. Before closing up shop that week, I had spent much time pondering the thousands of letters, mopping the floor as I tried to detect a pattern or cipher. One critic theorized that Paw was simply transcribing a sequence of DNA—a rather good insight, I thought, until Mercy pointed out that DNA is a variation of the letters A, C, G, and T, of which only the first was found in the Hawaiian language.

“Hawaiian only uses twelve letters,” Mercy said. “Makes for rough Scrabble.”

When we got to the gallery the rain had started, and the unseasonable warmth had turned the inside jungle-humid. It was too early in the year for air-conditioning, and Dora asked me to bring up a portable cooling unit from the basement. I nodded, but there was no way I was going to do it. I had a new shirt on, which would certainly get smudged, and I was with Mercy, freshly affianced, who at that moment was drifting into the installation in the next room.

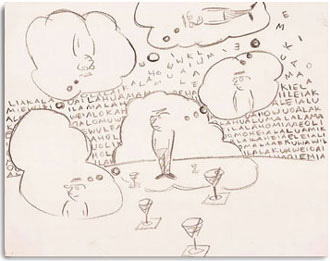

The Dizzies was pure confusion. The environment was both obvious and enigmatic. It consisted of, among other things, a dozen electric fans, of various sizes and vintages and rotating at various speeds; a blizzard of pages, torn out of 365 paperback books, which fluttered to the ground and were periodically broomed across the floor by semiclad women in headdresses, onto a hidden conveyor belt that brought them once more to the ceiling-mounted dispersal system; walls covered with 1,776 Polaroids in which Dark Red Paw and his painstakingly constructed alter ego, Red Dark Paw, gave each other tattoos depicting mobius strips, concentric circles, and flaming tomahawks.

The Dizzies was pure confusion. The environment was both obvious and enigmatic. It consisted of, among other things, a dozen electric fans, of various sizes and vintages and rotating at various speeds; a blizzard of pages, torn out of 365 paperback books, which fluttered to the ground and were periodically broomed across the floor by semiclad women in headdresses, onto a hidden conveyor belt that brought them once more to the ceiling-mounted dispersal system; walls covered with 1,776 Polaroids in which Dark Red Paw and his painstakingly constructed alter ego, Red Dark Paw, gave each other tattoos depicting mobius strips, concentric circles, and flaming tomahawks.

“Max,” I heard Dora call, intent on having me smudge my new shirt and lose face in front of Mercy. I was already engrossed in The Dizzies, nodding my head to the aggravating soundtrack.

I had felt not so great that morning. Weekends we arose at the same late hour. In the shower, embracing my soapy and pensive fiancée, I felt a drop of water infiltrate my left ear, and despite a concerted, daylong effort, it seemed determined to stay put. Now my right ear felt out of sorts, too—to say nothing of all the gray matter in between. It was enough to make me forget which ear had admitted the water.

I tracked Mercy’s blue cocktail dress amidst the falling pages of type and the whirr of electric fans. I tried to identify the roving dyads nursing room-temperature Cabernet. Some of them knew me, even knew me by name, but pointedly avoided eye contact. Gradually I lost her in the tumult. The Dizzies turned the world to murmur. I noticed that the pattern on the floor—the floor that I had scrubbed, the day before—described a maze, and I doggedly followed one promising path, kicking patches through the paper, until it reached a dead end. In the aluminum petal of one of the slower moving fans, Dora swam toward me, intent on covering me with smudges. I concentrated my gaze on one of the Polaroids. But then Dora kept walking, trudging across the carpet of potboilers. She had found Mercy, who was talking to the man whose tanned and inked torso I had just been fixating on: Dark Red Paw himself!

I could hear Dora coo hello, could not hear how Mercy introduced herself, could not gauge if Dora took Mercy to be Paw’s latest manic-depressive muse. Probably she did. I tried to imagine Mercy as another Ida McNut. Someone said something about Hawaiians only using a dozen letters, and how that would make for a tricky game of Scrabble. My joke! Suddenly the chop-chop of a fan sounded way too close, and my legs lost all muscle. I instinctively thrust my arms out, hungry for context. Paper flew up all around me like a squad of startled pigeons.

I could hear Dora coo hello, could not hear how Mercy introduced herself, could not gauge if Dora took Mercy to be Paw’s latest manic-depressive muse. Probably she did. I tried to imagine Mercy as another Ida McNut. Someone said something about Hawaiians only using a dozen letters, and how that would make for a tricky game of Scrabble. My joke! Suddenly the chop-chop of a fan sounded way too close, and my legs lost all muscle. I instinctively thrust my arms out, hungry for context. Paper flew up all around me like a squad of startled pigeons.

I grasped, for a moment, the stem of one of the taller fans, which fell forward with sickening slowness. It landed on another fan, which fell, crashing into another one. The whole daisy chain took fifteen seconds but seemed to last forever. By the end, only one remained standing. There were no injuries, though a thin smell of electric smoke littered the air and the blades of one of the fans had torn up a small percentage of the 1,776 Polaroids. A newspaper photographer snapped away, even after a teary Dora told him to stop.

Some debate ensued over whether I was then required to buy The Dizzies. It would cost two hundred grand. It also necessitated having a spare room in which to put the whole extravaganza. Dora was furiously trying to remember the gallery’s insurance policy. Fortunately, Dark Red Paw was whooping with joy. He was a vigorous old salt with a healthy white mane and a silver bird-shaped amulet around his neck. Apparently he felt that my inadvertent destruction actually improved the piece.

“Leave the fans where they are,” Dark Red Paw told the semiclad headdressed women. He clomped me on the back and called me a genius. Red Dark Paw was clearly a creature of superior moral fiber. His amulet appeared to be made out of a foil gum wrapper—a medium Ida McNut had recently employed.

Dora was frowning but at least looked less homicidal.

“I won’t be in on Monday,” I told her quietly.

“You better not be.”

As it turned out, she had little reason to be cross with me. The Dizzies sold a month later for the lordly sum of $555,000. Though I never dared step inside Dora Travertine—or any gallery—again, I would eventually derive some satisfaction from the thought that I had collaborated with the one and only Dark Red Paw, that most generous of visionaries. My fall had proven the point—the efficacy—of The Dizzies. Having discovered, over the course of my life, to be more or less free of talent, I’d found at last my art of imbalance.

When we left the gallery, Mercy asked if I’d fainted.

When we left the gallery, Mercy asked if I’d fainted.

“I’ve never fainted before,” I said. “What does it feel like?”

“The blood rushes away from your head.”

“This was more like the world rushed away from my head. But I feel fine now.”

I suggested ice cream, but it was too early in the year for ice cream. It was too early in the year for ice cream, for air conditioning, for open-toed shoes for men. Everyone agreed that the world was not hot enough yet, and yet it was. The rain had stopped, and now little pools of silver brought out the topography of the pavement. There was a little wind but it was quiet at last. Steam rose unsteadily from manhole covers, and trash fluttered softly in the alleys. As we turned the corner, the sidewalk was replaced by a chunk of rubber, and I gripped Mercy’s shoulder with a hair-raising yowl.

“What’s wrong?”

“Everything.”

Then the avenue shimmered, more river than pavement. I counted to ten, exhaling after each digit. My next step seemed to land several inches below sea level. I whimpered and swore and Mercy hailed a cab.

When we got home, I found to my horror that someone had replaced the apartment’s hardwood floors with a thick layer of hardwood-colored gelatin.

“Sofa,” I moaned, tumbling into the cushions.

The following weeks were full of mystery, mortifying embarrassment, and dull rage—though if I could see footage of myself, face obscured, I would probably laugh. Every audience loves the hapless klutz. Sensations were cross-referenced, contraindicated. Life became suspense: There was no telling what would trigger a spell. I learned to fear crowds, color, and repetition. At the grocery store, the rows of brightly colored potato-chip bags made me look away, to the array of dazzling salsa-dip jars to my left or the fluorescent stacks of powdered-detergent boxes. On the subway, trying to maneuver myself into an open seat between two passengers, I would invariably sit on one or the other, until I learned to simply clutch a pole, clamping my eyes shut as the miles swam past.

At last I went to see a doctor, then another, then the specialist, Dr. Motion. I told him about The Dizzies, about the water in my ear. Could a drop really unleash so much chaos? He doubted it. He explained something about the structure of the ear, rich with metaphors—labyrinth, drum, hammer, canal—then said he didn’t think the ear was the problem. He had me walk across the room, at a diagonal, with my eyes closed. He asked me to focus on his finger as it zoomed in and stopped an inch away from my nose. He turned my head from side to side. When I sat on the examining table, feet dangling, the gray hospital tiles looked like the tops of clouds. Everything was a canyon. I would let it linger for a year. Then it was time for the Swamp.