Clouzot’s Wound: Lara Mimosa Montes on L’enfer

28.04.15

What can be gleaned from thirteen (unlucky) hours of exposed footage?

Ø

glean /glēn/ verb

to collect gradually bit by bit

to gather the leftovers

as in after the harvest

Ø

In 1964, the French director Henri-Georges Clouzot ambitiously set out to film a project he would never finish.

Ø

This project was first titled Du Fond de la nuit, then La Ronde, and finally, decisively, L’enfer.

Ø

To get to Hell, start from the bottom of the night. Circle outwards and counter-clockwise.

Ø

Clouzot scripted L’enfer to begin with an end. Marcel, the husband, holds a razor as he regards his sleeping or dead wife, Odette. What happened? Allow the unverifiable facts to demand your attention. Speculate. Ask questions.

Ø

Does the film begin with a jealous husband hovering over a murderous precipice, or, worse, has he already committed the final act without his yet having realized it?

Ø

Marcel and Odette. If it sounds a little Proustian, that’s because it is, and so to speak of this film is to indulge in the Remembrance of Things (not yet) Past.

Henri Lefebvre’s The Missing Pieces aspires towards the same impossible task.

Ø

“A catalogue of rather impressive effects. But no scene. Not the slightest.” – Claude Mauriac

Ø

As L’enfer “ends” with the word ETC. rather than FIN, one can surmise that from “the beginning” the film was never meant to be “finished.”

Ø

Many scholars would have us believe that the subject of L’enfer is the jealous husband’s paranoid projections. Take for instance the scene where Marcel approaches Odette, whose body seductively stretches in the couple’s shared bed. In an attempt to join her, the husband grows frantic as he discovers his wife shielded behind a cruel, curved, transparent wall. Desperate, he stretches his arms and fingers wide in order to touch a distant (or dead) wife.

Ø

Little has been said of Clouzot’s collaborator and first wife Véra, who co-wrote the screenplay for La Vérité as well as starred in three of her husband’s films, among them, famously, Les Diaboliques. In 1960, two weeks before her 47th birthday, Véra died of a heart attack. It’s an uncanny fact because five years earlier, in Les Diaboliques, Véra’s cinematic double, Christina, had already died the same death.

Ø

If L’enfer is a movie about a man possessed by his thoughts, then these thoughts revolve around the fear of losing one’s grip on a thing intensely loved.

Ø

In December 1963, Clouzot married his second wife, Inès.

Ø

Every screen test is a repetition of a trauma not yet past.

Ø

Clouzot was an insomniac as well as a perfectionist. (I want what I want and will stop at nothing to get it.)

Ø

In 1964, Americans too wanted nothing less than the moon. After investors from Columbia Pictures previewed the auteur’s first test rolls, everyone cried unanimously, “Oh! Clouzot!” Here, take the money. Take it, it’s yours.

Ø

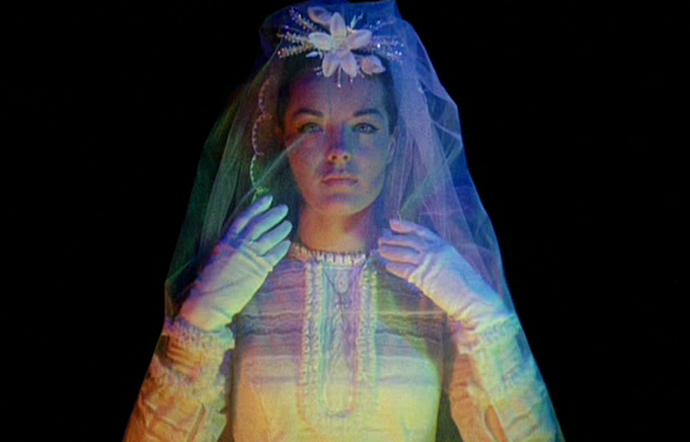

See the images of Romy Schneider open-mouthed and starving.

Ø

If L’enfer is Clouzot’s botched attempt to reconcile himself with a lost love-object, then Marcel (who plays a paranoiac) is a symptomatic stand-in for Clouzot, the melancholic.

Ø

“The complex of melancholia behaves like an open wound . . . ” —Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia”

“Your wounds opened again.” —Clouzot in a sound test for L’enfer

Ø

“I had this idea which was to dramatize the feeling of anxiety I have every night,” Clouzot admitted. Can’t sleep. Can’t think. What do you call the state I’m in?

Ø

Anxiety, which Heidegger understood as the “dizziness of freedom,” is one of the tautological affects of stress. When anxiety reaches a critical mass, a man may feel thwarted by his obsessions as his ability to reason becomes hyperbolically thrown out of whack.

Ø

In L’enfer, Clouzot infamously projects his stress onto all his cinematic objects. There’s the scene on the gorgeous Garabit arch bridge where, in the foreground, a topless twenty-six year old Romy Schneider lies tied to the train tracks while a whistling steam engine approaches. In black and white, the footage, rife with suspense and unavoidable dread, looks and feels like a Hitchcock, even more so as the train stops dangerously short of running over the panic-drenched woman. Such effects, however, are an illusion, for the scene was originally shot in reverse with the train proceeding backwards and away from “the distressed.” It’s sadism for the sake of a very seductive and well-executed cinema trick, but I also read in such scenes the auteur to be both the engine and the actress. Is there not something of the death drive looming in all this?

Ø

Clouzot chose the steam engine because its whistle sounded like a screaming woman. Elsewhere in the studio while experimenting with some sound tests (Clouzot wanted to depict his protagonist’s aural hallucinations), the auteur speaks into the microphone the words, rien, rien. Nothing. You’re safe.

Ø

Foucault describes anxiety as “the vertiginous experience of simultaneous contradiction.”

Clouzot may have been torn between the living and the dead. Which wife would he love and at whose expense? Véra, whose death he had “written,” or his newlywed, Inès?

Ø

“Seek nothing. Forget.” —Clouzot

Ø

Once Clouzot’s lead, Serge Reggiani, walked off set, under duress, Clouzot’s confidence cracked. Production ended shortly after he suffered (like his first wife) a heart attack.

Ø

In the shadow of such strange events, L’enfer appears as a portrait of a man distressed by the memory-trace of an imminent death. What’s left? A series of eternal returns, circling the question of the husband’s hand in it.