Chic and Virtuous Doom: A Conversation With Feliz Lucia Molina

11.03.14

Undercastle, the most recent book of poetry by Feliz Lucia Molina is a veritable gecko of a book, a work of variegated form and sentiment.

Undercastle, the most recent book of poetry by Feliz Lucia Molina is a veritable gecko of a book, a work of variegated form and sentiment.

Molina has an uncanny ability to shape a moment with her compositional choices, often shifting from sprawling prose to tight lyrical verse. She even goes so far as to cross out whole sections of poems, leaving her process bare on the page.

There’s a youthfulness to Undercastle, a sense of being in a weird, plasticky past, largely because Molina often explores the decades of her youth, the 80s and 90s. This world permeates her poems. It’s a world in which kids strive for pop culture perfection, people communicate in mysterious “pager speak,” and the sitcom life is idealized. Dead poets don’t appear in the book, but make “cameos.”

Feliz and I “spoke” via email between Los Angeles, CA and Northampton, MA. We went deep, talking about the influence of cities on her writing, Pamela Anderson and the “ghosts” surrounding her work.

BLAKE BERGERON: In the first lines of the first poem, “Strip Mall Heaven” you make reference to Baudelaire. In the dedication of Paris Spleen, Baudelaire writes that the poems inside are “child of giant cities, of the intersecting of their myriad relations.” Do you feel the poems in Undercastle relate to the “giant cities” you address (Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Buenos Aires) in a similar way?

FELIZ MOLINA: The poems relate more to sidewalks or discount stores in a suburb. I’m thinking of a Los Angeles suburb because its most familiar. “Paris, Las Vegas” was written in the Paris Casino & Hotel in Las Vegas and “Buenos Aires” had to do with skyping with a friend who was living in Buenos Aires. Sub means under and the poems are subby in the sense that they are under something. I was playing with the concept/image of wealth pervading hilltops and the not so wealthy obviously not on hilltops. This binary operates the other way too. I think I used Baudelaire as a launching pad to begin the poem. Like a cameo appearance of some movie actor who guest appears in some TV show and your like, “wait, I recognize him from somewhere, what movie do I recognize him from?” That’s the way Baudelaire operates in “Strip Mall Heaven.”

BB: In “Red” you write, “we can’t see ourselves / when trapped between celebrity and war news.” In “Indigenous Strip Mall America” you write, “we could have died / from too much Pamela Anderson / we would have been alright with that // because she’s so many things / made of all that beach and silver screen.” Are we all doomed to lose ourselves in an ocean of celebrity and war culture? Can poetry offer some type of escape, or should we give up and accept “all that beach and silver screen”?

FM: Maybe the doomed-ness of things is chic and virtuous. For the privileged spectator (which is everyone is who uses the internet?) war and celebrity news is “beach and silver screen” in the sense that we are sending, sharing, clicking and receiving purely text/image/sound (events). It’s a beach. It’s on a screen. Hello Death. It’s a fuzzy image of everyone drowning in imagery. In “Indigenous Strip Mall American,” Pamela Anderson functions in a similar way Baudelaire functions as a recognizable thing; a thing strictly recognizable. “We will have been alright with that” is a gesture of ambivalent drowning. Everything move through an ecology of money and desire; things are an assemblage of more things like how words mean other words. Ambivalence is a way of holding your arm on the wheel. In this poem, Baudelaire and Pamela Anderson are equivalents to the extent that their images pervade the silvery ends of memory within the larger system of celebrity. Maybe it’s a play of acceptance and resistance of all that beach and silver screen.

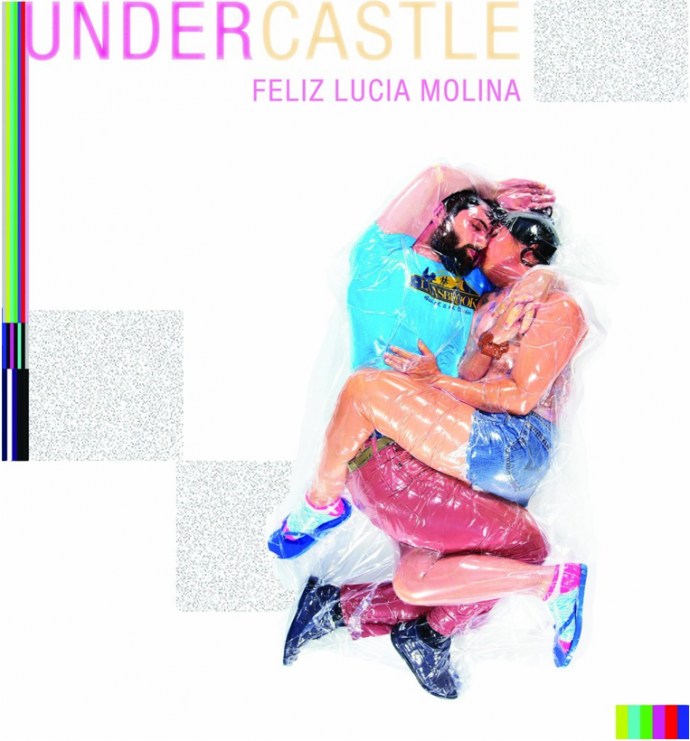

BB: I can’t not ask about the cover of Undercastle. The whole process seems so out there I’m not sure where to start, so I’ll just let you explain it. However, in doing so please address the following figures: 1) 10 to 20 seconds and 2) 5 liters of lube.

FM: I wrote about the experience of being vacuum sealed in a plastic bag. It appeared as a chapbook called An Essay of Things About Someone I First Met and Hung Out With For One Day in Tokyo (Magic Helicopter Press) which I haven’t seen. The process is described in a matter-of-fact way.

The artist Haruhiko Kawaguchi, known as Photographer HAL, is based in Tokyo and goes around the city asking couples if they wouldn’t mind being stuffed in a vacuum sealed bag and photographed.

It requires going to his studio and going into the plastic bag and lying down and him and his assistant positioning your body however way they want and holding your breath for 10-20 seconds. All this while you and your partner slowly lose air to reach an unsatisfactory climax; the point before suffocation. You leave your body in the care of someone who is sucking air out of you with a long vacuum tube. You don’t need lube to do it. I thought it looked interesting and I wanted to try to do the process myself for the cover of Undercastle.

I emailed Photographer HAL asking for permission to do this and he said that I couldn’t vacuum seal myself in a bag and that he would do it for me if I traveled to see him. Ben Segal and I had the chance to live and work at Haisyakkei Art Residency in Toride, Japan, which is a suburb outside of Tokyo. We traveled between Toride and Tokyo to meet with Hal. In one day it took several hours to take a few photos. By the end of it we were given cold gel packs and oxygen cans and green tea and soft chewy candies. The series is called Flesh Love and the next iteration is zatsuran which is a series of photographs of couples with all their things. I wanted this image from Flesh Love to be included somehow in Undercastle because I like how we look like packed meat at the supermarket. After all, we are human meat packaged however way in cars, institutions, systems, and desires. The photographs capture this in a frighteningly honest and crystal clear way.

BB: In the poems “Full House” and “Punky Brewster” we find dreamy, semi-philosophical descriptions of the opening of Full House and an episode of Punky Brewster, two staples of late eighties/early nineties television. Have you always had this penchant for incisive pop-culture analysis? Did this penchant in any way lead you to poetry?

FM: In the eighties and nineties my parents operated board and care facilities for mentally and physically disabled people. At a young age I was aware of the need to escape the environs of this type of household (which I later came to understand was a heterotopia in the sense that it was an alternative to the hospital or asylum) by watching television. Unknowingly, I tried to move from one heterotopia to another. Full House was like a private fantasy island. Michelle, Stephanie Judith, and DJ Tanner were exotic figures because I couldn’t relate to them. They had blonde hair and spoke good snappy English and lived in a cute two-story house in San Francisco and basically had three dads. Watching how things happened in the Tanner household was fascinating. I wrote “Full House” and “Punky Brewster” not to try to analyze the shows in a soft and fuzzy philosophical way, but also as an exercise in recollection, a sort of memory campaign of the TV shows’ impact on memory. I tried to enter into those heterotopias by inscribing myself in them.

BB: Family and cultural identity loom large in Undercastle. Were these areas you intended to explore in putting the book together? Were you in some way trying to engage ghosts from your past the way Demi Moore did with Patrick Swayze in Ghost (1990)? If so, who was your Whoopi?

FM: Objects and things in (in these poems) float around in the varied layers of cultural identities/formations or ‘cultivation of the soul’. Ghost had to do with an experience I had as a caregiver in Buffalo, New York. I worked night shifts taking care of an elderly woman who was mostly bedridden. The most she could do was sit in a wheelchair, eat, and watch movies on her television. One day the movie Ghost was playing. I started to write while sitting on the couch watching Ghost with her. I wanted the thick walls between screen and life to thin out. Sentence by sentence I tried to shave away the distinction between what was happening in the movie and what was happening while watching the movie. I wanted the (NYC 1990) world in the movie Ghost to seamlessly collide with our (Buffalo, NY 2011) world. I wanted Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore and Whoopie Goldberg to be stripped of all their signifiers by rendering them ambivalently; using language as a passive road flattening truck to flatten them like paper dolls. Is it possible to achieve (whatever nostalgic nineteen nineties) affect without understanding the references? I’m pulled toward that space between recognition and non-recognition of signifiers. Culture is the weather, is the over-arching sky or context for where it all takes place underneath.

My laboring role as her caregiver and companion and watching the movie with her was something that felt urgent to capture. It felt like I was on the edge of death with her. And there we were watching Patrick Swayze portray a ghost who tries really hard to communicate to Demi Moore through Whoopi Goldberg. It felt like all five of us were on this edge of life together. Movies have a way of directly invoking ghosts from the past. It was a ghost that belonged to the year 1990. Death appeared from different angles: the movie, Patrick Swayze’s actual death, the death of time, the approaching death of the elderly lady. I recently found out that the elderly lady died and thinking about this now, it feels like they’re all in the same place, if at least in the story Ghost.

I think Whoopi will remain Whoopi. I have no surrogate Whoopis.

BB: What’s next for you?

FM: Los Angeles needs more rain. Forthcoming in this California drought is a collaborative epistolary novel The Wes Letters (Outpost19) with Ben Segal and Brett Zehner, which is a bunch of letters to an elusive (non) Wes Anderson. I’d like to work on a screenplay, write more essays, make more drawings and videos. Ben Segal and I are starting to make chapbooks for friends and the first one is called This Will End in Tears by Kendall Grady. I’m gathering poems for this tiny journal called H A N D S where I handwrite every poem, which makes two versions of the same poem: typed and handwritten. It’s a way to be closer to a poem, to feel a poet in my fingers like a finger puppet.