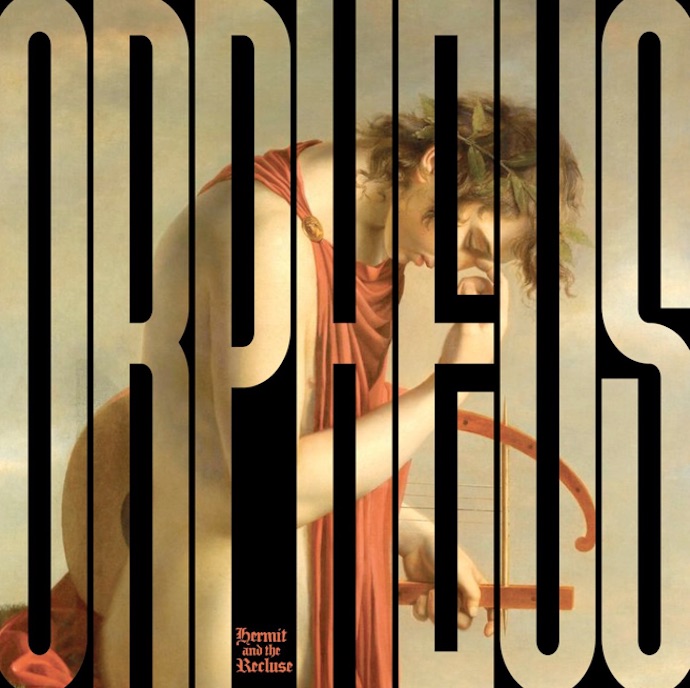

Book Album Book: Katabasis (Hermit and the Recluse, Orpheus vs. the Sirens)

11.02.19

Part 8, in which we journey to hell & back. Previous installments can be found here. Read in any order.

First you will reach the Sirens, who bewitch

all passersby. If anyone goes near them

in ignorance, and listens to their voices,

that man will never travel to his home,

and never make his wife and children happy

to have him back with them again. The Sirens

who sit there in their meadow will seduce him

with piercing songs. Around about them lie

great heaps of men, flesh rotting from their bones,

their skin all shriveled up.

—The Odyssey (trans. Emily Wilson)

Side 1

Let us return to the underworld, for it is cold here, and perhaps we can warm ourselves by the fires. Only, don’t drink from Lethe unless you wish to forget the way back. And recall our warning: Cerberus will let you in, but you will have to fight your way out. And whatever you do, turn no stone with your heel, unless you wish to hear every shadow’s story, in hopes you will remember them to the living, should you go back to the cold, supernal earth.

Should we descend, the dead will also ask us news of the living—those that may live to love them still. We might ask how they do not know whether those loved ones breathe: would they not mingle with the shades, if they no longer walked with us? Though perhaps they are so numerous, they pass through one another unaware. And those dead might then ask us how we come to them, heavy still with muscle and bone. And here we find another dilemma, we who sing the records of the dead: for we may remember them to the living, but those lost voices cannot hear our news.

One person’s hell is another person’s storyline. Or feed. Song functions to recall the dead, though we cannot return with them. The dead stay in the underworld, and they stay in our songs. We sing them as well to soothe ourselves, but it doesn’t work, or not for long. Or it is penance we repeat as prayer. We wish to be forgiven our forgetfulness, our lack of perpetual care. We want to believe that if we hold someone forever they can’t leave, and neither can we. But we know the truth: we can die in each other’s arms, and we can die alone. Mostly we die alone. And we sing of the dead, as though we are singing to them. But we sing to the living. The dead cannot hear our songs, or if they do, they can only sing along on records, and some of these will outlast us.

How do you tell your story and the story of your people? This is the epic imperative.[1] Where do others leave off and where do you begin?[2] You have to reach the edge of the circle of life and cross to the other side, to move through the circles of hell. Stakes is high.[3] You have to visit the dead. You have to bring something back. You have to visit the past. You have to take your life back. The circle of life, then, runs through the circles of hell.[4]

The sirens[5] will get you but not tonight. Only their songs are not so pretty, the ones tearing through the city on a voyage of death, flashing blue and red. If you tie yourself to the mast, it’s not to hear a beautiful song that will make you forget your home, though it might take your humanity, whether or not it’s out for your life. If you tie yourself to the mast to hear these sirens, it’s to hear them as they are, all they portend, and perhaps to speak the truth. And who will unstop their ears and hear you?

Want a world of superlatives? / Come see Ka. As on 2015’s superlative Days With Dr. Yen Lo, created under the mask of the doctor in the title, Orpheus vs. the Sirens is helmed by alter ego(s), Hermit and the Recluse. Behind the masks is Ka and his crew,[6] shoving us into ever deeper waters. Yen Lo takes its cue from The Manchurian Candidate, borrowing dialogue to set its scenes. Orpheus samples dialogue primarily from Jim Henson’s Storyteller, the “Greek Myths: Orpheus & Eurydice” episode. Its genius is in isolating the heaviest moments from a light treatment, and building an Argo[7] from humble materials. Dense mythological references are layered over contemporary urban landscapes: self-mythology and state of disunion mapped onto classical references.[8] We sail toward a fathomless understanding of hip-hop’s mythological roots in epic poetry.[9]

Ka’s song goes, One day they gonna get me but one day ain’t tonight, while the chorus echoes One day ain’t tonight. It goes, Be careful, because everything I say is admissible. It goes, Mommy dipped me in that river Styx.[10] It goes, That man sing that he ran things but couldn’t walk with us. It goes, In Brownsville I speak the shit that got my man killed. It goes, I’m ill-prepared, stupid ready. It goes, I speak the ugly elegant.

We could quote all this dark night, but hear Ka say it.[11] Listen at the edge of Erebus, the stand at the mouth of Hades, lit only by the beat of the shaded gro(o)ve.

Side 2

…Black blood flowed out. The spirits came

up out of Erebus and gathered round.

——The Odyssey (trans. Emily Wilson)

Do the dead sing each to each? But we are the dead, and they live in us.

Katabasis is descent to the underworld.[12] What we have to gain is to know for a moment what the dead know. What we have to lose is everything we thought we had. We have to die twice for that knowledge. Or we have to die three times: once to cross over to Hades, once to cross back and die into life, and once to never return to the land of the living. But this bears repeating: the dead will not embrace our trespass, except to ask us to remember them. But they would as soon take our life to spite us for our hubris, which they match in their assurance: should we get back, we will remember. And we will tell. Though Cerberus may tear out our throats.

There are many ways to tell a story, which happens only after the events, and becomes part of what it tells. Madeline Miller’s Circe tells us this, reminding us that what we have heard is the story of the men who told it. Did Circe beg at Odysseus’ feet, having begged at her father Helios’ feet, etc.? Or had she finished with begging by the time she gained an island of her own? And were Odysseus’ men the first whose rough hunger she had to contend with (and transform)? Had she not turned herds of city-sackers into swine before the storied crew touched her shore? Homer offers her as a monster on a map, but if her own story was untold, it was there to be written; if we were misguided, we wanted only a different guide, another channel.

So with Ka, who gives us his version of another myth, the singer who failed to bring his friend (or his love) back from the dead. He might, however, have given us immortal verse. If his friend does not live there, in the song, his memory does. And Ka lives both in song and in the world, which we are lucky to share with him.

And as we visit the dead in song, we visit the underworld, just as the singer sings himself from one world to the next. Everyone must die, Orpheus, Hades’ Queen Persephone tells him.[13] So to be with the dead we must die, and to visit the land of the dead, we visit our own death. It’s good, then, to have a song to follow back to the land of the living.

———————————

[1] And it begs the question: who are your people?

[2] And where do you leave off?

[3] Track 3, “Orpheus,” drops a reference to a crucial statement of intent, De La Soul’s 1996 album of this title. Meanwhile (and 22 years later on*), Orpheus vs. the Sirens goes “Sirens,” “Fate,” “Orpheus.” If fate stands in for vs., we have a reversal of the album title in the sequence, the end (flashing lights) in the beginning.

*In numerological terms, 22 sounds like decisions, decisions, precarious stability & rupture: 2, 2, 2+2=4.

[4] Drama had to run its course, Ka raps on his visit to the underworld of track 8, “Hades.” Or as Curtis Mayfield has it in the opening cut to his 1970 album Curtis: Don’t worry / If there’s a hell below / We’re all gonna go.

[5] Not dignified here as a proper noun, the sirens of this world are no longer the singers in the sea. So these sirens are dishonored as an all-too-common noun.

[6] including Animoss at the production helm, Ka no longer sailing alone

[7] Argo (from the Greek argos, which means swift) is the ship of Jason and the Argonauts in the Golden Fleece quest that took them across the world to the far edge of the Black Sea. No existing vessel could complete such a voyage, so Jason had the Argo built for the quest (Athena came up with the design). The ship was constructed of oak from the sacred forest of Dodona (where an Oracle second only to Delphi in renown was located). The ship could therefore speak and prophesize, and would come to save its crew. (greeklegendsandmyths.com/the-argo.html)

[8] Nor is this Ka’s maiden voyage into classical waters to snag the Golden Fleece. Yen Lo carries the lyrics: Take on Jason and his Argonauts … Mission after mission (“Day 110”).

[9] We speak of profound, if not unknowable, depths, and we focus here on the primary themes and tonal shades of this album. Of course, hip hop does not dwell only in darkness and death—nor does this album. The joyfulness and celebration may be more subtle here than in scores of contemporary hip hop albums, as Ka samples the book of the dead, which goes by many names in other versions (“The Dead” in Emily Wilson’s recent translation of The Odyssey, “Orpheus & Euridice” in other katabasic tales). Hip hop is rooted in story and poetry, and is a form of literature to anyone who has not pressed wax into their ears. We could not build a craft for Book Album Book without a lifetime of navigating the vasty deep of music from which hip hop fills its sails. So too has Ka swam through libraries and sailed through oceans, as Melville had it, or, as Ka samples Orpheus, I have been to the end of the world and seen things more terrible and more beautiful than I thought could be. These visions return to us as we sing them, and we cannot have beautiful visions without terrible ones.

[10] Charon polls the dead over this river as they enter the underworld, and gods swear on the river Styx, which is their most solemn vow: the antidote to the fickleness of the immortals, if you catch them in a promise.

[11] See the Book Album Book playlist.

[12] Or vice versa: there are many descents, and one descent to the underworld. Or two, if we live up to the epics.

[13] Sampled from Storyteller on track 8,* “Hades.” As the singer battles his conscience and the laws of nature, he makes his appeal to the gods of darkness. He’s defiant (What doesn’t kill you only makes you live-r), casts his own shade (Fuck the fake deep), and is ultimately remorseful: I’m still trying to recover / Might not ever / Rest in peace Kev.

*Sequenced in infinity, as appropriate to recording a trip to hell, where death is forever.