Book Album Book: About US

13.05.19

Part 11, in which we double up & down. Previous installments can be found here. Read in any order.

Life is a spoiler, but we do well to respect people’s desire to remain ignorant of what they have not seen or read—in literature and film, anyway. So if you haven’t seen Us but don’t mind reading about its soundtrack, and you don’t want to know who dies, who killed them, what Hands Across America (and smart speakers) have to do with it, and whether the cops will come to the rescue (spoiler: they won’t), save the footnotes for later. In the main body, we will try to stick to details you could glean from posters and trailers, or a typical timid film review, but in the footnotes we’ll go deep into the shadows in the water.

This Side

Something is wrong. As soon as we hear the ominous chanting,[1] we know we’re in trouble. The vacation home won’t protect us from what must be coming. And the music cues us to its infernal, unholy family lineage.

Just as filmic art inspires and comprises cultural discourse, albums track our thinking. We want to write around the music, just as we experience the world around music. In a film, in a theater, this is doubly layered. But the theater is surrounded by another theater.

The doubled character looks back at the actor looking at themselves as they are and are not. We too see ourselves seeing ourselves. As ever, it’s US against the world.

What is rising below the surface, to become the surface? The swell of a string section, the punctuation of drums, a tear across the orchestral field: the surface is an unbearable silence, obliterated by dissonant, swarming acoustic forces. Just so, the horror film gets its charge as much by what we hear as by what we see. Jordan Peele casts his actors in darkness. If a room has a shadow, his characters are drawn there. But he also puts them in the harsh light of day, right there with their nightmares: standing on a beach, lounging in the sand, driving down a suburban block in an SUV. Never safe from what you know: they are coming. And because you know, you gather yourself and go to war.

That we are at war with ourselves is at the heart of Us. It’s an American film.

In a film packed with literary devices,[2] there is a literal device: Ophelia, the smart speaker and errant servant of a white family in their vacation home. Ophelia is listening. When Ophelia is asked to play the Beach Boys, Ophelia complies.[3]

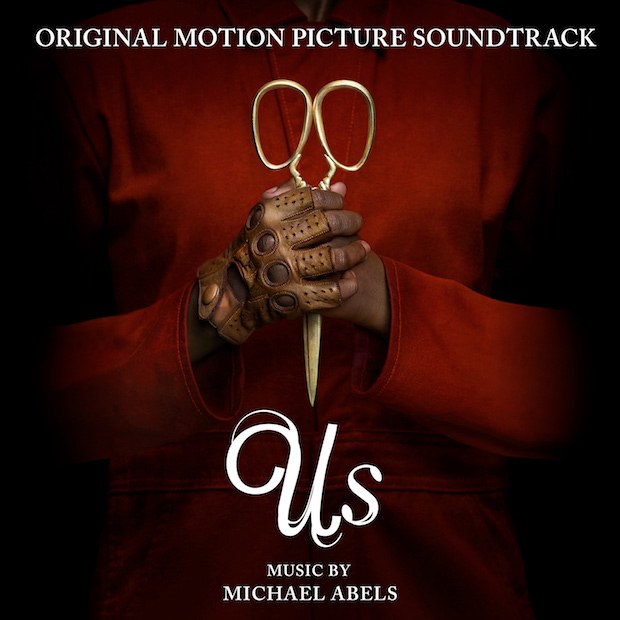

The analog device, if not quite analogous to Ophelia, is scissors, a household tool, and one of the first weapons handed to any child. Scissors in the film are a device to signify both joining (as in the mechanism of blades bolted together) and splitting (as in the action and effect of scissoring)[4].[5]

Underside

Perhaps, though, there is an analogy between Ophelia and scissors in the film. Ophelia is an interface, and in Us the interface connects film (as mise en scène) to music.[6] It is a transmission between those in the room and an archive of music, of representation: a stream that leads only to cultural artifacts.[7] Scissors, too, are both a connection and the severing of a connection. Like any technology, they are tool and interface (an interface of parts, and of scissorer and scissored). They are also intertextual devices that connect with other horror-suspense films like Dead Again, a murderous, looping, intimate nightmare Peele has cited as an influence. For now, that interface transmits one way, past to present, even as it runs through us—as it runs through Us. But the film’s use of scissor imagery, like its implicit connection to the slasher film, will insert it into the ongoing intertext of horror films, and transmit to the future of cinema.

So does the film’s soundtrack interface with other soundtracks, both original and compilation scores. We can stream a version comprised almost exclusively of the original music cues (and a remix of the song “I Got 5 on It”), but there also exists a version with more of the songs inserted into the film.[8] Michael Abels’ orchestral score recalls classic film scores while more directly referencing The Omen, and Minnie Riperton’s “Les Fleur,” which plays during the closing shot and credits, also opens an intertextual portal to Inherent Vice, another trippy beach film that features the song.[9]

Us is less a scary movie than an uncanny, suspenseful one.[10] This adds to the thrill of suspense, and allows us to see ourselves in this family, even if ours looks different. We see them as well as they are, even as we see them encountering (and struggling with) the problem of representation: you have to become what you fight, even if you are fighting representation (or the falseness of representation). For us (whoever we are) to be on screen, we must become them (ourselves on screen). This bears out in Us as actors playing doubles, which doubles the (false) doubling of actor/role.

Sunny Side[11]

We know our shadows will come for us in the night, but we see them in the day as well, following us from noon to sundown. If we are afraid of what is wrong, what is out of place—think again of the monumental horror-image, as when a naked person appears on the roof of a suburban home; or think on smaller scale of matter out of place: the rat in the toilet, or cat’s eye rolling down the hall—those moments when there should be nothing to fear—a day at the beach or walk in the park—can suddenly become terrifying. Dark clouds turn off the beach, a rubbery fin appears on the too near horizon, a man sidles out from a bush.[12]

via GIFER</>

When horror comes for us under the sun, we find that we are closer to hell than we tried to believe.

Night Music

Any song sounds different at noon and midnight. Any motif can brighten or sour. The art of the score is to turn a theme over and over until it knows us by heart. There are those motifs that signal transformation of an individual or relationship, or that auger a dramatic shift: a shadow crossing a sunny interaction. And there are those relentless motifs that always signal what is wrong, what should not be but is, what is coming for us. We know the great white’s song.[13] We don’t remember a moment where it might only have signified a creature moving through the deep. We know only it is coming toward the shore and we are drifting from the shore, and though we might stick to the horizon, there is always more below us than above. And there is always fear of what shimmers below the surface. The shadow from the deep, which we cast and which will swallow us up.

That no shark appears in Us, but we are reminded that the shark exists, that there was and will be a shark, puts us ill at ease, even as we chuckle at the audacity of a character named Jason who loves masks and wears a Jaws shirt. Us is a naturalistic film that does not feel real, or feels at moments irreal[14] or hyperreal.[15] We are continually translocated via filmic references that both place us here and there and remind us that where we are is in film. The music cues cue us as well. We are, that is, re-placed. We are replaced. Lights out in the theater—we’re going to the sunken place.

[1] which summons The Omen

[2] including heavy doses of intertextual reference, doubling and parallel structure, foreshadowing, and employment of what Sean T. Collins calls the monumental horror-image

[3] When Ophelia is asked to call the police, Ophelia plays “Fuck tha Police.”

[4] Jordan Peele, in an interview with Entertainment Weekly: “There’s a duality to scissors—a whole made up of two parts but also they lie in this territory between the mundane and the absolutely terrifying.”

[5] and they are notably used near the end of the film to reproduce one of its monumental horror-images, an infernal/supernal† double for Hands Across America, as a paper chain of scissorlike people holding hands (or fusing, tethered one to another).

† as supernal humans are tethered to their infernal shadows, the horrific parody of Hands Across America is a supernal re-enactment of and by infernal tethered beings, though they are now tethered to one another, having cut out and replaced their supernal others, all across this land

[6] Meanwhile, that interface is pointedly cut off from others (Ophelia can only call “Fuck tha Police”).

[7] The name of the device is a cipher that might evoke the stream in which Ophelia’s body floats: Another watery metaphor that does not come to rest.

[8] A shadow version (or streaming playlist) of the hybrid score/comp would include songs Ophelia had access to: The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” and “Fuck tha Police.”

[9] “Good Vibrations” appeared as well in Vanilla Sky, which in its ironic usage also tapped into the psychedelicate, Mansonic bad vibes just under the All-American surface for Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys.

[10] Its protagonists outlive their fear, and it is beautiful (even revolutionary) to see Black agency in a horror film.†

† As discussed in the marvelous documentary series Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, Black agency (and survival) is not unheard of in horror films. But however rare, that agency is often qualified or curtailed in racially charged ways, as in the fate of fearless, resourceful Ben (played by Duane Jones) in 1968’s Night of the Living Dead, who survives a zombie apocalypse only to be shot by meat hook-wielding white militia at the end of the film. Jones went on to play the lead role in Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess (1973), again with a qualified sense of agency as a wealthy archeologist on his estate who finds himself undead and thirsty for blood. (Ganja & Hess is notable, and highly recommended, as a counter-Blaxploitation art/horror film with a brilliant and ambitious original soundtrack by Sam Waymon, brother of Nina Simone.)

[11] To scare the living daylight out of someone is perhaps to appear on a beach, arms akimbo, facing away, blood dripping from your fingers. That child will have to draw your image later, in crayon. And this act will have tethered the child to its fate: to meet himself on the other side, and not know which is which. One child wears a mask; one wears a Jaws t-shirt. Both† are portals to other worlds, just as every cinematic reference is a hole cut into the film, through which we might crawl, or be dragged.

† And ah yes, both wear masks.

[12] Or the uncanny finds us in broad daylight: a frisbee with a triangle on it lands on a towel covered in circles.

[13] And perhaps there is a punning double and parodic homage here with the grandiose orchestral (white) Hollywood film score and its infernal double in the horror score. This is after all a film of bad mirrors meant to captivate and thrill us to death.

[14] as in an imaginary reality one experiences as real

[15] where reality is strange and extraordinarily vivid, packed with significance