Body Map: Ears

30.06.14

It’s like being underwater: the loudest thing you hear are your thoughts. Voices are garbled syllables with distorted time signals, they are far off and distant. It is easy to ignore, easy to give in to the indulgence of living in one’s own head. This is what it’s like to be semi-deaf, to be increasingly deaf.

The pressure is not all that different. You feel sounds like the weight of water pressed against your skin. You learn the intimacy of reduced language, elevated constructions stripped to murmurs and grunts. It’s primal and unimpressive. Eavesdropping is out of the question, so you study other conversational cues. How she is holding her body. His eyes darting across the room. You learn the language of faces. You learn to read bodies. Sometimes the writing is so painfully obvious you look away. Other times you can’t. Still: it shocks you how much people say without words.

The safety in a lack of stimuli. The feeling of slipping beneath water. The hanging quiet as you float. You are suspended.

* * *

In 1992, I am 7 years old and in the first grade. Every Wednesday is art class. We shuffle down the hall single file until we reach the windowed room, decorated with art projects adorned with a kaleidoscope of tissue paper and sunbursts of finger paints.

The art studio large and airy, with cupboards full of supplies and many windows. Natural light pours in, and it’s the kind of place any kid would love, free to daydream, to create his own imaginary world.

The teacher has a pronunciation key of her name above her desk. It’s a matted illustration of a shoe, a mouse and a key, connected by plus signs. Shoe-mouse-key. How to pronounce her impossibly-spelled name, translated for elementary students.

We line up to pick squares of tissue paper from plastic bins. I watch the other students and follow their lead. I select a variety of colors: pinks and yellows and greens. The boy in front of me gives me a strange look, then says, “You’re gonna get in trouble.” For what, I wonder. I shrug at him and walk back to my table.

I spread out my squares and begin to work. Shoe-mouse-key is standing in front of me. “What are you doing?” she asked. I look up. What to say. I don’t know, so I say nothing. Her voice booms at me for taking more than the allotted two squares of paper. I feel the breath escaping from my open mouth. Too many squares, I took too many. I want to explain that I didn’t know anything about two squares, but how?

Weeks later, Wednesday. I’m in art class again. Minutes in, I need to use the bathroom but am terrified to ask. I don’t want Shoe-mouse-key’s attention on me. I decide to hold it instead. When that doesn’t work, I choose to piss my pants. Strategically. Slowly. If I do it slow enough, I think, it will be absorbed into my clothes. Maybe it’s not even that much.

This is not what happens. What happens is I am paralyzed by the force of piss pushing its way out of my body. The warmth gushes down my leg, down the wooden stool I’m sitting on, puddling bright yellow on the speckled white linoleum. The students at my table are disgusted. The curly-haired girl sitting across from me is wearing an open face of disgust, her mouth twisted into a grimace. She brings her hand up to her nose to ward off the stench.

Shoe-mouse-key stomps over, notices the pool of piss on the floor, and starts yelling. “What is wrong with you?” she asks. I know I am a stupid, disobedient idiot, but I don’t understand why.

* * *

You fixate on what you can understand: images of a shoe, a mouse, a key. These are comforting. This you can read, you can interpret, even when you can’t hear. But there are no visuals for spoken instructions – no handouts with steps one through three, no numbers telling you how many squares of tissue paper you’re allowed to take. Just the teacher yelling at you and your classmates looking at you funny. In homeroom your name is on the board with two check marks next to it and for what, you don’t know – you just know that if you are sent to the principal’s office you don’t know how to explain to your parents that you can’t explain any of this.

* * *

After several rounds of tests, it is decided that I need hearing aids. Tests meant spending hours alone in a soundproof booth with a glass panel, where I watched the top of the audiologist’s head move, brown-haired and thinning. I wore headphones and listened for words and repeated them back to him, words like ice cream and baseball and hot dog and popcorn, overly enunciated, always growing dimmer or louder. At the faintest point I could hear muffled sounds but couldn’t make out any of the words. I kept fitfully silent: Was it better if I guessed? Did this mean I failed? What did failure mean? Wavelengths were tested in the form of different pitches, a series of dull tones and whines piped into my ears. I was instructed to press a joystick button when I heard sound.

I started bringing my advanced math homework to work on during appointments. As my mother and the doctor discussed the state of my ears, I’d pull out my workbook and furiously scratch my way through a problem. I couldn’t hear, but that didn’t mean I was stupid, too.

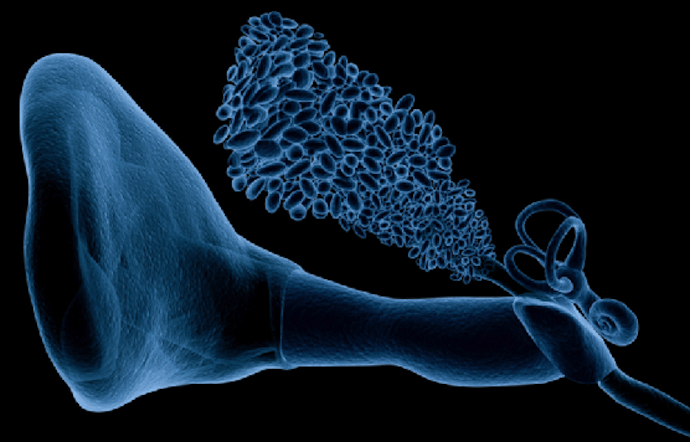

He squeezes soft, cool putty into my ear. I hear a soft plastic whir as it fills my ear canal. The posters hanging in the room depict the ear with various degrees of anatomical detail. The three parts – outer, middle and inner – are broken down further, reduced to tiny, intricate bundles of nerves, tubes, and bones that look like they belong to a mouse.

His hands move around my face, smooth, clean, hairless as a child’s. He has immaculate nails and smooth cuticles. The pressure is gentle but taut and the coolness quickly turns to ticklish warmth as I sit there, waiting for the mold to set.

The finished products are chunky, grey-brown lumps of plastic. The volume is adjusted by a wheel with spiky grooves that grips your finger. A crescent-shaped door swings open to hold the battery. Despite the dollhouse-like quality of their miniature features, there is nothing obscure about them. These tiny pieces of machinery feel foreign in my head, their delicate circuitry succeeding where my own biology failed.

My mother takes me to meet with Shoe-mouse-key, to explain my newly-discovered disability. I understand every word: genetic, hereditary, hearing loss, hearing aids. The art teacher is warm and friendly. She apologizes to me. She didn’t know. She tells me I can talk to her anytime I want, though I never will.

* * *

I am obvious now. I am my ears. The other kids make fun of me, call me names. Computer ears. Deafie. I sink down in my seat on the bus ride to school. I hear every word now, loud and clear and crisp. Sometimes the noise is too much. When the world gets too loud, I take the hearing aids out, turning my world underwater again.