Body Map: Headlessness

03.06.14

“Scrub extra hard,” the nurse said, “y’aint going bathe again for a while.”

She handed me a thin stitch of soap and papery blue booties and a papery blue dress. I shut the door to the cavernous shower stall and scrubbed extra hard.

It was 5 a.m., very dark in surgery intake. I emerged in my paper clothes, calm and flat, used to hospital procedures at that point, without marvel. I set myself onto a bed where I’d stay for the whole summer, headless.

They started in with the IVs, and no matter how much I tell each new nurse that my veins are thin and rolly and likely to blow, each new nurse tries it her way until it fails. This time a multi-poked failure patch found a rolled vein and a jet of blood spurted from my arm onto the chest of my plus one, my boyfriend at the time, who promptly fainted.

Then I was officially alone. The anesthesiologist came in, chubby and glowing like a movie star, and she told me to start counting back from ten. Cold crept up my arm and then I woke up.

The seven hour surgery to remove the tumor that had been growing behind my eyes and the 53 hour coma afterwards where no one went, especially not me, was not even a tick-tock, just a tick-and then someone telling me it happened.

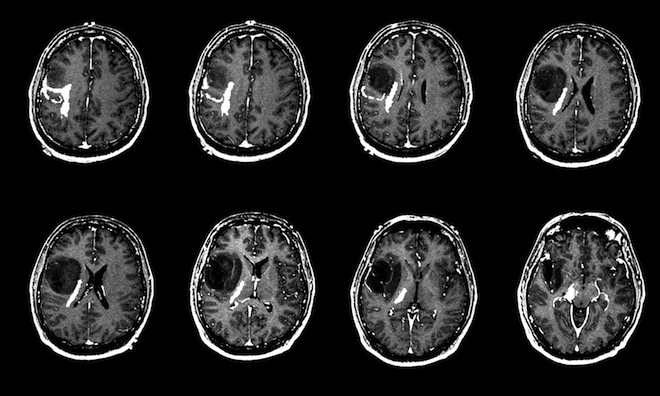

Like when I was told I was losing my vision and I was weirdly lactating because I had a brain tumor, pea-sized, pressing on my optic nerve, growing into my pituitary gland. Not cancer. Just a cellular malfunction—stubborn cells, stubbornly not disappearing but huddling up. I was told, I was shown. See there? That bit, you know, he tapped the MRI image. I saw but did not know.

A cellular malfunction. No purpose, no meaning, no particular intent. When I was told, I saw the Flower Sermon but Buddha holding up not a meaningless wordless flower for no one to understand except Mahākāśyapa but a small pea-sized, scallop-edged, rubbery tumor. For no one to understand, period.

I grew my brain tumor in private. I went to class, wrote poems, walked up and down the big West Virginia hills. I mostly told no one. I was fine. And not. Like most people.

Then I woke up from surgery. A bandage sealed over my nostrils, which were stuffed with gauze and held open with tiny metal stints. They had cut the bottom connections of my nostrils open a bit to widen the passage for the laser that would enter my sinus, pierce through my skull and sear the tumor into bits to be removed with a tiny grasping claw. Like the old Egyptian mummification process, how they’d pull pieces of the brain down through the nose with a hook, that was me, the mummy.

Now on the bed I was awake but I was somewhere new in my body. My head was gone. That I that lived here had moved down and “I” was in my chest and stomach.

Someone was feeding my missing head small ice chips with a plastic spoon. It struggled with the ice slivers. I wanted to go back to sleep but people kept talking to me, wanting me to eat the ice and nod my head. I could not tell if I was nodding. They wanted me to move my arms. I laughed a little in my guts at their concern. I would be a hero if I moved my arms right now, I thought, and lifted one arm up to great acclaim. My arm signaled to me in a new route—more direct. Without head-processing. I felt my arm like you’d feel eyes blink. Close up to self. Blink now. Feel it? Right there. Next to “you.” Special, only, brain-self. Imagine that but in your chest.

Time passed in uneven chunks, blurry light or dark rooms where someone else was always in charge of my body and its requirements. I was wheeled down a hallway and I heard the nurses joking about the bald shaved spots on my head which had been outlined in purple marker. Sensors had been attached there for MRIs before the surgery—triangulation, he said—in case they came off, they could be realigned to the markings. “Nice purple rings,” they said, I heard it through my intestines.

My body was left in the ICU for a while. I was crouched in my stomach. Here’s what I did for weeks: I listened.

I couldn’t see and I couldn’t smell or taste and I couldn’t move much to feel anything. I didn’t know anything about my head but that it was boarded up in gauze and I didn’t live there anymore. But I could hear—all through my body.

I was patient, content to listen, alert and curious about the sounds in the ICU, beeps and groans, wheels wheeling, a phone ringing, a hissing pump, little ticks, gurgling, shoe squeaks if running happened, pad flaps if walking. I listened intently to the sound of someone’s lungs being sucked dry of fluid at regular intervals. Words imposed grossly over this. Most patients in the ICU are not in the position for much talking; it was the nurses who would talk. They arched nets of intimate words over my bed, dumb chatter, cruel things sometimes, disgusting stories about patients, explicit sexual exchanges, evil rants, boring small talk, just regular people at work. They worked around me, a deaf empty body, coldly protecting their own energies from the drain it would be to consider anything more than their patient’s physical maintenance. It was ok; I was busy anyway.

I made games of trying to move each toe or twist my ankles back and forth slowly in regular patterns. My legs had voices. No my calves, my ankles, my thighs, my feet all had voices. I lived in them. I saw the world out of my ankles.

What does the world look like out of one’s ankles? It looks a little better, honestly.

I felt what I could feel with my hands. I edged my hand inward and felt a thin tube taped where a patch of my pubic hair had been shaved off. Later I would also find marks there from the same purple marker they must’ve used on my scalp. My arms were stiff and dead from too many punctures and too much stillness; I could not bend my elbows. After the nurses had run out of normal puncture spots on my arms they had moved onto my hands and fingers and my neck. My arms swelled and bruised over yellow and blue. They were tired. And deep tired anyway, of being me, executing my commands, shoveling food to head, holding and turning and writing and hitting. They lay like soft logs and seemed happy, finally sessile.

It was, I don’t know, June. I slept, oozed, drooled, and forgot everything about my regular life.

Then my feeding tube came out. Some bandages came off. Visitors had brought me photos of themselves standing next to the old me, beaming together in the incorrigible safety of normalhood. My eyes grew open and the head was seeing. But it was remote, like backwards through a telescope. I was in no way connected to the information my eyes were now gathering. Trays of real food were delivered to me like jokes.

I turned the head to look at them: the hard fried chicken piece and roll and wet green beans and honestly boiled laughing inside. They trays would eventually be removed, replaced with new ones when I was left alone. My mom had come to West Virginia now to help and she’d spoon broth into me, or my boyfriend would when he could get away from work. Otherwise that was that. Chewing endeavors ceased when boyfriend noticed I had chewed straight through a small part of my tongue in attempting to eat some bread he’d given me.

I was to be moved out of ICU into a regular room. A physical therapist came to move my limbs. She lifted my legs and bent them at the knee repeatedly, in a goofy staged kick, then cheerily moved onto my sore arms. I groaned to let her know it hurt, surprised at the sound. “You really need some pillows under your arms!” she said, pronouncing pillows as “pillers” in the Appalachian style. The catheter came out. I’d have to start walking to the bathroom. “You are young and healthy,” my neurosurgeon said when he came to visit me. “Others have it much worse. You should be walking.” My morphine button was taken away while I was asleep.

The wires to my head were waking up. I would be lying if I said I was happy to have my head back.

For a while I’d lived on a small scale, listening for sounds and living in them, breathing patiently, moving body parts with steady, pleasant or pained focus. Pain cleans out worry. It puts you in this second, then the next second, and nowhere else. I know it can make you mean, but only heads can be mean. I was lucky. I felt rich from decapitation. More advantaged than those still attached to that awful organ. I wasn’t wondering why why why anymore, what did I do, how did I grow this tumor, how can I be ok now, what what what. Just quietness.

This coming from the kind of person who had lived, as introverted writers/readers do, almost exclusively in her head, regarding her body largely as an irritating, irrational corporation that demanded constant and utterly unappreciated maintenance. The original me would have much preferred bodilessness, and in luck of all lucks here I was with headlessness instead. My head could not have understood that what I needed was its removal.

In the regular room a woman was wheeled in who at first just groaned horribly or slept. Eventually I saw her up and about, an enormous stretch of stitching up one of her legs and running across her scalp. Once she approached my bed and pointed at her scars. “They was looking for the clot!” She said, “God works in mysterious ways!” Mostly she said that. She’d say it when she woke up. She’d say it when I’d throw up on myself. I’d lay there with hot vomit on my chest, pulling steadily on the nurse cord, mad. God works in mysterious ways, she’d whisper under her breath. She got better, then started asking the nurses for cigarettes and was gone soon after that.

And then I missed her saying that. I said it to myself sometimes. Not believing in god exactly, it became more of a no one works in mysterious ways; no one works in no ways after a barf or a pain. It was kind of a constructive fuck you. Especially to knowing, which had enormously left me. And it turned me—where before you live in absolute horror of the thing, of the pain, of the meaningless cellular malfunction your brain is bashing against, then it is not the pain or the horror or the malfunction that stops existing but your higher-order brain, the very instigator of rotten interpretations of meaningless things.

I started walking. I went outdoors even. My boyfriend helped me outside onto the sad patio. He bought me a lime slush and I sat in the fresh summer afternoon, feeling clean air finally on my gross skin, watching sparrows picking at crumbs, feeling a throb growing in my head.

I almost always dreamed about wading waist-high in Lake Superior until I came to a river of darker water. On the other side of the river, another lake, just as transparent and deep as my lake. From a slant I could see shipwrecks at the bottom of the other lake. I’d stand before the river border between the two lakes, looking but not crossing.

I was released from the hospital without a cellular malfunction and instructions to check regularly under my nose for any clear watery fluid and return immediately if any was detected. “It would be your spinal fluid leaking out of your nose,” the nurse said flatly. Because of the stitching in my sinuses I would not be able to bite or chew much, nor lay flat in bed, nor tilt my head forward farther than a few degrees. I was told to not blow my nose for at least six months. I was told that if I sneezed I should return immediately to the hospital.

Sewn back on now, my head rethroned itself as tyrant. I remained in bed, mostly watching TV with vague interest, too tired and distracted to read, and besides I could hold my arms up very long at the angle I needed to hold a book perfectly level to my exhausting head. If I looked down I felt a flood of hot pain behind my eyes.

Then cake, cake, cake, I only wanted cake! I wanted a food I could mush up without much tooth work, and something flavorless and sweet, since I still could not smell or taste. The void between the flavorlessness of foods and how flavorful I knew they ought to be—a blueberry, a lump of peanut butter—drove me mad. I ate what I knew wasn’t cheating me of anything.

My head spoke up and out and over everything; my head wanted and complained and schemed and envied and nagged and hurt and hurt and hurt. My boyfriend washed me in the tub like a baby. My body fell back into silence. The summer went on like this.