Bats of the Republic: A Piece of Unnatural History

22.10.15

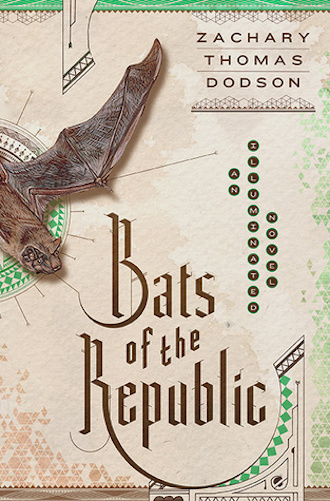

Bats of the Republic: An Illuminated Novel

Bats of the Republic: An Illuminated Novel

by Zachary Thomas Dodson

Doubleday

448 pgs / $27.95

One of my favorite buildings and spaces to be created while I lived in Washington, DC was the Museum of Unnatural History at 826DC. Founded in 2010, 826DC is part of Nínive Clements Calegari and Dave Eggers’s 826National initiative. Each outpost has its own space within the city, with a themed storefront dedicated to selling goods and a back space dedicated to teaching and supporting young creative minds. Washington, DC’s outpost houses unnatural history: artifacts and fossils found by the fictional legendary explorer Montana Smith, including jars of unicorn tears and the skeleton of a beast with horns, wings, and a tail.

In much the same way, Zachary Thomas Dodson’s Bats of the Republic captures the childlike imagination still present in adults, however hidden and small. Dodson’s book is described as an illuminated novel, an obvious nod to the illuminated manuscript, a tradition in which text and illustration combine, dating back to AD 400-600 in the Western world. In this way, Dodson has lovingly crafted a text that not only includes multiple books-within-books (one of which has been pierced through by a bullet on every page) but hand-drawn sketches of animals and more unnatural creatures, such as the Numrat of the (real) family Sciuridae and the (fictional) genus Ankyloglossia.

However, rather than evoking the religious texts so prevalent to the craft of the illuminated manuscript, I would venture a more modern comparison to the kind of books regularly produced by McSweeney’s, BatCat Press, and Zachary Thomas Dodson’s own featherproof Books. While these independent presses and designers have the ingenuity and, perhaps, integrity to craft unique books, convincing a mainstream, large publishing house like Doubleday to follow through with equally sharp attention to detail, as Dodson has, seems a daunting task. Surely, this is also a credit to Robert Bloom, Dodson’s editor at Penguin Random House, who speaks proudly of Dodson’s work.

The six years of hard labor Dodson shoveled into Bats of the Republic is evident not only in its beautiful layout, but also in its precision of narrative. Characters names curve and twin in ways both obvious – a glance at the Character Tree foregrounding the novel reveals similarities between Zadock and Zeke Thomas, Elswyth and Eliza – and more obscure – Zadock’s horse is named Raison D’Etre; Zeke’s best friend is Raisin Dextra. Once you begin looking for these doppelgängers, you start to see them everywhere. In this way and many others, Bats of the Republic feels haunted.

In some ways, this book is scary. It foretells a world in which paper is scarce, and penmanship a lost form. Every document must be filed with the government and housed in the Vault; every conversation recorded, every life phase adhered to. It is a segregated world filled with bigotry and grand scheming. Politicians are snakes, Senators are double-crossed, and no citizens are truly safe. Offset that with Dodson’s Wild West of 1843, filled with actual snakes, bats, and tenuous relationships forged between explorers and American Indians, and, despite several ambiguous sightings of chupacabra, I think I’d rather hang out there.

I have to admit, I haven’t been a big fan of steampunk; the whole mindset of re-imagining a past era based on steam never really appealed to me. I think that’s why I was surprised to find myself embracing the steam-powered future world of Bats of the Republic. While weapons like the steamsabre, with its polished pecan hilt and pommel, carry an old-fashioned sensibility with them, it’s hard not to find comparisons between them and modern devices such as water cannons that police have used against rioters and demonstrators. Contrast this with Dodson’s much more pared down inclusion of steam in Zadock Thomas’s 1843 landscape. While there are fantastical elements to the 19th century narrative, it is clear he has quite a bit of local knowledge and historical knowledge of the then-Republic of Texas; a timeline of the territory’s flags is just an example of the historical information Dodson has packed into this book.

It is fair to classify Bats of the Republic as science fiction-meets-historical fiction, yet this novel is also built around a mystery. It pulls at that thread slowly, carefully, at first, building toward a whirled unspooling over the (exact) final third of its pages. Here again, we have that high level of fidelity; we are taken, quite literally, into the darkness of the cave, and while the lights may come back on, our sense of order and stability is never fully restored, even at its signed, sealed, and delivered conclusion. Ultimately it is this device of the maze, expressed here in the form of the cave, that elevates and potentially relieves Bats of the Republic from its traditional narrative structure. While I can see some readers becoming irritated by this deviation, I had the opposite reaction; here, my interest was piqued. I like to think of this physical blackout as Dodson’s “time passes” moment, a la To the Lighthouse.

The Museum of Unnatural History in Washington, DC has a cave of its own, unveiled in 2011 with a ribbon cutting featuring Toledo, son of Montana Smith. It would not surprise me at all to find Bats of the Republic here, tucked away between a can of Wallace’s Condensed Primordial Soup and an issue of Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern. Zachary Thomas Dodson’s novel is more than just a book, it is an artifact in and of itself. It is a key to both the future and the past. Like Building Stories and The Jolly Postman, it can be taken apart and looked at through many different lenses. It is a book worth holding in your hands, a book that can’t be appreciated on anything but paper.