Bad Business is Good Art—Fonograf Editions

21.06.16

As clearly stated on my copy’s back cover, Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift is “a modern classic.” For those on the outside of that classic-ness, though, The Gift is about people giving other people gifts. Kinda. Originally published in 1983 and subsequently brought out in a new edition in 2007, Hyde’s book explores the nature of both ancient and contemporary “gift economies,” economies that fundamentally work outside of traditional commerce or market-based concerns. It further delves into “contracts of the heart” and how they drastically differ from legal contracts borne out of capitalist considerations.

The central percolation of The Gift is summed up by Hyde as this: “How, if art is essentially a gift, is the artist to survive in a society dominated by the market?” Which makes a lot of sense. If I write a poem or short story or novel that’s good but no one buys it—not because it’s not good, it is, but because no one really buys poems or short stories or novels, at least not to the degree that would allow me to fully live off those words alone—where does that leave me, the artist? How do I make it and/or what’s the point? In The Gift’s “Conclusion” chapter Hyde comes up with “three primary ways in which modern artists have resolved the problem of their livelihood: they have taken second jobs, they have found patrons to support them, or they have managed to place the work itself on the market and pay the rent with fees and royalties.”

For musical artists that last choice might still be feasible, but for literary artists the common choice is taking second jobs. Some teach. Some work in bookstores or restaurants. Some sell their souls to the devil and write copy, thereby massaging art-based concerns into market-based ones. And no matter what option the artist chooses to take, Hyde states, she must be willing “to be poor” in service to her art. Hyde uses Walt Whitman and Ezra Pound as examples, declaring that “[n]either man ever made a living by his art.” That’s certainly true—and the same can be said for millions and millions of other artists. As more astute thinkers than myself have pointed out, art is an insensible proposition, one that very often asks more than it gives.

And yet year-by-year the proliferation of artists seems to, universally, grow ever-larger. To a certain degree it’s a mystery—and yet not. For all its detractions (and there are many, from solipsism to pettiness to wholly-irrational jealousy), the one thing art has—and has always had— going for it is the promise of engagement beyond one’s direct source of self. Regardless of its form, no piece of art is ever created in a vacuum, and, even if you the artist are unaware of your distant and immediate predecessors, there is a power in that scope of community. In some subtle but significant way what is now was once before. There’s an inherent gift, then, in that premise.

Having read it six or so years ago at this point, The Gift didn’t perforate my mind again by accident. Instead, it upmerged into my consciousness because I recently started a vinyl record-only poetry press entitled Fongraf Editions. And in a strictly economic, market-based sense, starting a vinyl record-only poetry press was foolhardy. Certainly I’m one of those people that other people like to complain about—I have a lot of vinyl records. I listen to them daily. I further have neither a smart phone nor an iPod. (I do, however, have a Zune, Microsoft’s failed version of the iPod. Zunes were discontinued in 2011. RIP. I love me some Zune.)

I thus possess quite a few spoken word poetry records, ones by Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore and Wallace Stevens. To be honest I don’t listen to those records all that often, but, as a poet, I cherish them. All of them were brought into the world by Caedmon Records, a label that once upon a time made heaps of spoken word records (here’s an enlightening interview with one of the label’s founders, Barbara Holdridge). Caedmon was an early pioneer of the audiobook landscape and was eventually bought out by Harper Collins in 1987. With the steady decline of vinyl sales, Harper Collins eventually ditched the vinyl and turned Caedmon Records into the solely compact-disc producing Caedmon Audio. Which is all fine and well—but as has already been established I’m a loser for vinyl; having grown up in the CD era, I have hundreds of them, but compact discs don’t much do it for me anymore.

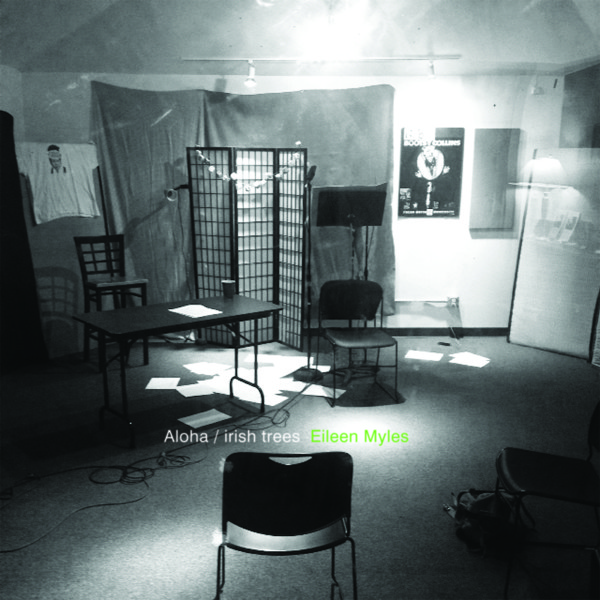

So for the last three or so years I’ve dreamed about starting a poetry press that would put out all their “books” on unreadable vinyl records that could solely be played and heard. And with the significant help of my friends at Octopus Books, in the past year I was able to actualize my poetry-vinyl dream. Eileen Myles’ Aloha/irish trees, Fonograf Editions’ first record, came out on May 17th and prior to that date we had a pre-sale extravaganza—free books, broadsides and fake tattoos with the purchase of a record—to get people interested. And if all goes according to plan our second record, Harmony Holiday’s The Black Saint and the Sinnerman, will be out by late summer/ early fall. So what’s the problem?

Well, there isn’t one—or at least not in a gift-economy world. In a market-based one, though, there potentially might be. There’s a reason why Caedmon Records turned into Caedmon Audio, namely that making vinyl records is A) very expensive and B) outdated. It’s true that in the past five or so years there’s been a resurgence in vinyl production, attention and sales. However, in the age of YouTube and Spotify, that renaissance is really only occurring for a select group of financially-stable patrons. And although there’s definitely a market for the new PJ Harvey or Frank Ocean LP, the market is somewhat untested when it comes to poetry records. To be sure, asking Eileen Myles to record Fonograf’s first record was, with the past year and a half she’s had, a serendipitous choice. (To be clear, she’s always been one of my favorite poets—“Understanding Eileen Myles” was the title of one of the poems in a book I put out in 2014—and I initially asked her to participate in the project in March 2015, well before her justly-acclaimed I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems [which was coincidentally published by Harper Collins] came out in September 2015.) For Fonograf, though, it’s been a welcome and peculiar happenstance that Myles’ renown has seemingly grown exponentially since I Must Be Living Twice’s release. She deserves it.

But with all that said, even with Myles in our corner, all we’re really hoping for from the sales of Aloha/irish trees is to break even, thereby allowing us to make the next record—and hopefully that pattern will continue itself after Holiday’s The Black Saint and the Sinnerman comes out. One record begets the next, and market-based economy forces like “making a profit” or “solving the bottom line” don’t really come much into play. Or if they do, they’re happy accidents at best. Just the same as any other label, Fongraf’s records cost money, sure. They exist in the world of commerce. But the origin of the press, its central impetus, resides in a “contract of the heart” that from an outsider’s perspective—and certainly anyone outside the world of poetry or vinyl—makes no sense. That’s the point though. As trite as it might sound, in the end, contracts of the heart value the gift, its sheer giftness, over all else—the art of the thing rather than the value of it. We’ve made something we love and believe in because we love and believe in it, and, in having done so, are hoping to offer others the chance to love and believe as well.