And Now for Something Less Funky: A Fan in Search of Joanna Newsom’s Elusive New Epic

23.04.10

More like have three on me, amirite? Defensive sarcasm was an easy first response to Joanna Newsom’s Have One on Me, released last February by Drag City. Spread over two hours and three discs, on paper it sounded even more sprawling than it was. The 28-year-old singer, songwriter, harpist, and pianist already had a reputation for excess, which detractors and devotees agreed upon but interpreted differently: immoderation or ambition? The Milk-Eyed Mender featured extravagantly cracked vocals, while Ys indulged in epic track-lengths and Van Dyke Parks’ lush orchestral arrangements. Both albums were exotically spiced with many, many arcane lyrics. You either relished every bit or spat out the mouthful. I relished, and still winced a little upon hearing about the triple disc. It was hard to comprehend how the demands of Newsom’s craft, both emotional and technical, could be sustained on her end—and withstood, on ours—at such length.

More like have three on me, amirite? Defensive sarcasm was an easy first response to Joanna Newsom’s Have One on Me, released last February by Drag City. Spread over two hours and three discs, on paper it sounded even more sprawling than it was. The 28-year-old singer, songwriter, harpist, and pianist already had a reputation for excess, which detractors and devotees agreed upon but interpreted differently: immoderation or ambition? The Milk-Eyed Mender featured extravagantly cracked vocals, while Ys indulged in epic track-lengths and Van Dyke Parks’ lush orchestral arrangements. Both albums were exotically spiced with many, many arcane lyrics. You either relished every bit or spat out the mouthful. I relished, and still winced a little upon hearing about the triple disc. It was hard to comprehend how the demands of Newsom’s craft, both emotional and technical, could be sustained on her end—and withstood, on ours—at such length.

After the rumor and apprehension, the music arrived quietly, leaking only a week before its release date, and it instantly quelled my own reservations with the crystalline opening sounds of “Easy”: Newsom’s voice, high and fluted, against an atomized cloud of instrumentation. You only had to browse through the first disc to realize that the album was not some rambling mess—that it was, in fact, Newsom’s most careful and charted-feeling work to date—and that most of the excesses which had been a magnet for both adoration and criticism were gone.

Newsom’s voice is still veined with glass and wire, though it doesn’t chirp and squawk so much any more. The idiosyncrasies of her style are settling into more traditional, rigorous modes of jazz and blues, evoking Joni Mitchell by way of Ella Fitzgerald more often than the fairy-tale creature of her prior work (although the decorative, essential imagery of fairy tales still abounds). The songs remain long, but the arrangements (by Ryan Francesconi) are compact and wispy; less fussy and battering than those of Ys, with a lot of space around Newsom’s piano, harp, and voice. The length is justified by the subtlety of her writing, which draws you in slowly, and makes her prior work seem ingratiating and exhausting by comparison.

Those opening lines—“Easy, easy/ My man and me”—are somewhat deceptive, although ease is the dominant impression left by Newsom’s pliant phrasings and plentiful but tamped-down lyrics. She floats in from courtyards; tills the dirt of Eden with her bare hands; sleeps for forty years; gently dies over and over; all at a dreamy, breeze-borne pace. The emotional register is one of gracious friendship: the elegiac compassion that can bloom at the end of romantic struggle. It is a music of second chances, new beginnings, affectionate recriminations; of lost moments preserved in amber. First-person confessions lurk like shadows on a brightly wrought backdrop of musical puppetry: Funny animals, mincing aristocrats, explorers, saints, dragons and more all dance on strings. Newsom, as the puppet-master, operates beyond the realm where stories end unambiguously well or poorly, and longs for it. She plays fated archetypes against tactile sense memories of “the sound of you shaving—the scrape of your razor, the dully-abrading black hair,” the stubble drifting away like the moment itself, the image clinging. The lyrics turn excoriating at times, but always get back to tenderness quickly. It is a world of “terrible hardship,” she confides on “Esme”—the hardship of changing and dealing with changes in others. But “kindness prevails.”

That sense of kindness—which, for Newsom, amounts to a generalized forgiveness—runs through the music as well as the lyrics. It never jars or scolds; it’s calm and appeasing. Francesconi’s arrangements for brass, winds, strings, tambura, banjo, and mandolin avoid any sense of orchestral weight, accenting Newsom’s latticed melodies with bright harmonic and timbral counterpoints instead. Even the liveliest songs, like the gospel-infused “Good Intentions Paving Company,” hew to lean, braided pulses that never hit the feverish pitch of, say, Mender’s “Inflammatory Writ.” Fillips of energy run through “Easy,” but the baseline is a languorous canter, which carries through the entire album. And sometimes, as on “Occident,” accompaniment is all but nonexistent, leaving Newsom’s voice and piano to construct the delicately hulking melodic structures in a void. Even the longest songs waft by softly; a rather drastic change for someone who has always put a lot of sharp corners in her music. Those edges were places where intense emotions leapt out—anger, jealousy, heartbreak—but here, again, “kindness prevails,” smoothing the rough parts into a beatific current.

That sense of kindness—which, for Newsom, amounts to a generalized forgiveness—runs through the music as well as the lyrics. It never jars or scolds; it’s calm and appeasing. Francesconi’s arrangements for brass, winds, strings, tambura, banjo, and mandolin avoid any sense of orchestral weight, accenting Newsom’s latticed melodies with bright harmonic and timbral counterpoints instead. Even the liveliest songs, like the gospel-infused “Good Intentions Paving Company,” hew to lean, braided pulses that never hit the feverish pitch of, say, Mender’s “Inflammatory Writ.” Fillips of energy run through “Easy,” but the baseline is a languorous canter, which carries through the entire album. And sometimes, as on “Occident,” accompaniment is all but nonexistent, leaving Newsom’s voice and piano to construct the delicately hulking melodic structures in a void. Even the longest songs waft by softly; a rather drastic change for someone who has always put a lot of sharp corners in her music. Those edges were places where intense emotions leapt out—anger, jealousy, heartbreak—but here, again, “kindness prevails,” smoothing the rough parts into a beatific current.

But it doesn’t add up to an easy record to get to know and hold close in the manner to which Newsom fans are accustomed. Those sharp corners of yore scored the melodies into our memories with their strangeness, their violence. Have One on Me is Newsom’s most difficult album to get a handle on, her most remote and enticing. Without that sense of quirky excess, fans and critics, for the first time, are facing it without the defense mechanisms of outright dismissal or intuitive adoration. Suddenly, all of her “I” statements connect to a creature that seems more terrestrial and relatively plainspoken, more ordinary—more like us as we are in our real, messy lives, not in our romantic imaginations. Mender was easy to swoon for, with its spontaneous aura and scrappy arrangements. Ys earned its listeners with hard-won, grand-scale intimacy. Have One offers more circuitous, slowly paced rewards. We get ramification instead of revelation; depth instead of immediacy; reticence instead of bombast. It’s her best-performing album on the U.S. charts to date, which is not surprising: It avoids polarizing tics for a more centrist appeal.

I don’t think anyone can really claim to have digested Have One on Me yet. I’m not sure it’s digestible at all. Of course, there’s simply a lot of it, and many songs play with similar tonal registers in a way that makes the album seem like one big shape-shifting mass. The melodies unravel at great length, like secrets coming undone, often favoring the extended harmonic modulation of classical music or jazz over the hooky repetition of indie-rock. I’ve been listening for a couple months, and it still feels like walking through a foreign city I’ve been in for a week or two, as acutely familiar plazas and intersections alternate with lengthy spans of seductive anonymity, where only small details flash out recognizably: a window-box here; a certain awning there.

Its instantly legible peaks—for me they’re “Easy,” “Have One on Me,” “Good Intentions Paving Company,” “Soft as Chalk,” “Esme,” “Ribbon Bows,” and “Kingfisher” (you’ll have your own)—have in common a sense of melodic athleticism and clarity; and often, a blues- or gospel-based churn to offset the rarified air. They flow out into a sense of mannered unreality, in retiring songs that sound beautiful while they’re playing and then evaporate like breath on glass. “Easy” is the song that makes me want to begin the journey, but the more mysterious passages—the barely-there “Baby Birch” and the rococo “No Provenance”—keep me walking, in my desire for them to become known.

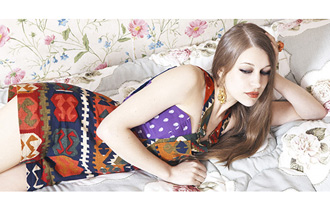

I had a similar blockage with Ys until I saw it performed live, when Francesconi’s stripped-down arrangements brought the melodic and emotional cores of the songs into clearer focus for me. I attended Newsom’s show at the Carolina Theater in Durham on March 25 hoping for similar clarification. She sat pertly at a harp that looked about twice her size from the audience. She wore her hair lustrous and straight, framing one of those forthcoming faces that seems built to scan from the balcony. She was charming and funny in a low-key, slightly practiced way, sipping at a chunky mug that you just knew contained some kind of evanescent tea. As she loiters somewhere between indie stardom and what passes, in this age of deracinated cultural power, as pop stardom, you can sense the planes of her public persona settling into something more approachable than the wolf-pelted princess of The Milk-Eyed Mender; a vortex for broader desires. On the cover of Ys, she was painted into a stylized iconography of the album’s themes. On Have One on Me, she is the icon, posed winsomely in a series of arty black-and-white stills that could land her the Scarlett Johansson role in a new Woody Allen film.

I had a similar blockage with Ys until I saw it performed live, when Francesconi’s stripped-down arrangements brought the melodic and emotional cores of the songs into clearer focus for me. I attended Newsom’s show at the Carolina Theater in Durham on March 25 hoping for similar clarification. She sat pertly at a harp that looked about twice her size from the audience. She wore her hair lustrous and straight, framing one of those forthcoming faces that seems built to scan from the balcony. She was charming and funny in a low-key, slightly practiced way, sipping at a chunky mug that you just knew contained some kind of evanescent tea. As she loiters somewhere between indie stardom and what passes, in this age of deracinated cultural power, as pop stardom, you can sense the planes of her public persona settling into something more approachable than the wolf-pelted princess of The Milk-Eyed Mender; a vortex for broader desires. On the cover of Ys, she was painted into a stylized iconography of the album’s themes. On Have One on Me, she is the icon, posed winsomely in a series of arty black-and-white stills that could land her the Scarlett Johansson role in a new Woody Allen film.

The live show made me appreciate the craft behind the new songs even more, partially by negative example—the Francesconi-led band felt tight and effortless on the Ys tour, but felt a little more timidly formed this time; once in awhile even verging on slipshod. A few mushy cues certainly didn’t ruin the show, whose ambitiously scintillating and interlocking motifs demanded a lot of musicians, several of whom had to handle multiple instruments. The string section, whose attention was less divided, shone. But while the band on the Ys tour seemed to play with Newsom, this one seemed to play around her, which is faithful to the album’s arrangements but felt a little stiff in the live setting. A long rendition of “Have One on Me” was polished and bristling with energy, and a rollicking version of “Good Intentions Paving Company,” where opener Fred Armisen came onstage and stood around ambiguously, elicited one of the best crowd responses. But however captivating the new songs were, the two she plucked from Mender—“Inflammatory Writ” and “The Book of Right On”—arrived with a sense of near-relief, like you get upon spotting a familiar landmark when lost. Still, seeing the band explore the songs, sometimes slightly losing their way, gave me a deep feeling of identification—after all, wasn’t I experiencing them the same way?

“And now for something less funky,” Newsom said after “Good Intentions Paving Company,” before slipping into the hushed, insinuating “Kingfisher.” The quip was telling. She must know that something a lot of fans love about her music—rough edges, spontaneity, a certain grit—is leaving it. That it has to for her to grow as a musician. That growth and change can be hard; a theme the new album both obsesses on and demonstrates. For all the benefit-of-doubt she doles out, she requests the same in return, especially from those who came to her music by way of indie-rock, not classical. Have One on Me asks for our trust and credulity; the lyrics make that kind of classically ethical appeal. Its emotional resonance is prismatic, alloyed, and so ample it can seem amorphous. When I left the theater, I didn’t feel as if I knew the songs any better, at least not in the way I’d imagined. But I understood that forestalled insight was built into the music itself. Newsom has abandoned the territory of epiphany for a furtive, liminal region: more daunting, equivocal, deeper. I realized that the songs were bottomless by design, and that I wanted to keep exploring them anyway.