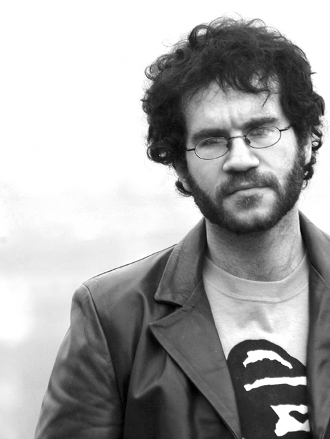

The Life You Save May Be Bill’s: An Interview with Tom Bissell

06.06.10

Tom startles the witch. After warning me about her, pointing her out, telling me to turn off my flashlight, admonishing me not to shoot in her direction, and generally giving me the sense that if the witch is startled, we are without a doubt done for, Tom startles the witch. I’m almost certain of it. He blames me for it, but I swear its him.

Tom startles the witch. After warning me about her, pointing her out, telling me to turn off my flashlight, admonishing me not to shoot in her direction, and generally giving me the sense that if the witch is startled, we are without a doubt done for, Tom startles the witch. I’m almost certain of it. He blames me for it, but I swear its him.

I am in Portland for a reading, and while I am there, I get together with my friend and fellow Upper Michigander (because I will not call us Yoopers, no matter how many times you ask) Tom Bissell, author of Chasing the Sea, God Lives in St. Petersburg, The Father of All Things, and now, Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter. It is—like all of Tom’s work—a dizzyingly smart book, cocksure and combative about its premise, revealingly personal when you least expect it to be. A damn fine book all around.

I am supposed to be interviewing Tom, but for the first two or so hours, we sit on his couch and play video games. We attempt the recent Resident Evil, but I’m not picking up the controls very quickly, so we replace it with Beatles: Rock Band. Tom is an experienced Rock Band drummer. I take up guitar duties. An old friend of mine from Wisconsin has joined us, and he plays bass. We let the introductory animation play through; it’s fairly stunning, this surrealist recounting of the band’s history. After that, we manage a serviceable run through the Abbey Road medley. It’s possibly the only time that Ringo has ever been the virtuoso.

After that, out comes Left 4 Dead, a cooperative zombie shooter that is simple to figure out: pay attention; keep shooting; run like hell when needed; help your buddies when they get pinned down or incapacitated by either the regular zombies or the more powerful Hunters, Smokers, or Boomers; and for God’s sake, don’t startle the Witch, a small female zombie that presents itself as a weeping child but can render a character prone and bloody in a single, furious, clawing hit.

On our first mission, I’m playing Zoey, a young college student and Tom is Bill, a Vietnam vet. It’s a character he has always avoided even though — or perhaps because –his book The Father of All Things is a travelogue through contemporary Vietnam with his father, a veteran. As we fight our way through a hospital to the safety promised on its helicopter landing pad, I sense that Tom is both on my side in this and also doing his best to mess with me. Everything is happening very fast and the witch is actually managing to freak me out. She runs in my direction screaming, arms lashing out. I know this is a game, but Tom is shouting, and the zombies are running in my direction, and the guns are going off all around me, and I am more than a little bit shaken.

And if it affects me in this way, doesn’t that mean that in some way this game matters?

Let’s start with the big question. Do you think video games are a form of art?

Let’s start with the big question. Do you think video games are a form of art?

Yeah. Not all games, obviously. But I think there’s no question that the medium has as much viability as an art form as any other. It’s just going to be up to individual game designers. To me, games are art because there are people creating them who think of themselves as artists, and there are people who respond to them as they respond to any other work of human creation. And so, to me the whole question is a non-starter.

I suppose you can start getting into questions of high and low art, but I don’t really think that way about stuff.

There are not many games that have startled me emotionally. I guess that my own personal definition of art is something that you go into one way and after your exposure to it you come out changed in a way that goes beyond, “That was awesome,” or “Oh, man, that was scary!” You come out of the experience expanded somehow. There are a handful of games that have done that for me—that have given me memories of what I’ve gone through that are really powerful.

I don’t think every designer, or even most designers, think of themselves as creative artists. Most of them think of themselves as entertainers and I have no dispute or debate with that. But the games that are really going to mean the most to me as a player are the ones that are made by people who self-consciously understand themselves as artists, like Clint Hocking [lead designer of Ubisoft’s Far Cry 2] and Jonathan Blow [independent game designer and creator of the innovative and popular game Braid, which revolves around manipulating time].

In Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics, he says he sees a lot of hand-wringing in the comic book industry about whether or not what they’re doing is art. His response is that the way to be culturally significant is to go to the party, sit down at the table and have something interesting to say as opposed to worrying about whether or not you have something interesting to say. You spent a lot of time talking to people in the video game industry—the people who made Gears of War, Jonathon Blow—so do you think that there is, similarly, too much hand-wringing there?

To me, Left 4 Dead, the game we just spent 45 minutes playing, is a superlative piece of popular art. I wouldn’t put it up against Casablanca or something, but as a piece of popular art I think it’s phenomenal work.

Here’s the problem with games. Even a really thoughtful, interesting game like Bioshock, say, when you describe it to someone and say it’s about Objectivism [Ayn Rand’s theory of rational self-interest] and it’s about how you deal with power, and it’s beautiful. People ask, “Well, what’s it about?” You say, “Well, you run around this underwater city shooting lightning out of your hands at psychopaths.” The reigning paradigm of game design is to send someone running amok through some system populated by enemies. And as much as I love those games, I think they will remain in the comic book ghetto until more designers figure out how to make enjoyable games that don’t involve picking up an armament of some kind. It’s not going to change the way I look at games, but I think that’s what it’s going to take to change the culture’s view of games.

So you think the violence has sort of put a mask over what at the core is interesting about playing games?

So you think the violence has sort of put a mask over what at the core is interesting about playing games?

I think that the violence puts up a wall between a large number of people who might otherwise be inclined to think of games as works of creative significance and those who don’t. But maybe that shift doesn’t have to happen. Maybe it’s fine that games are the way they are. I don’t know.

You mentioned Casablanca. Many who admire Casablanca admire more than just the story. They think of it as a master class in filmmaking. As good as the story and the acting is, what a lot of people—film people usually—focus on is the mechanics of it: the editing, the structure of the story. This is something I was thinking about when I was reading your book. You cop to the fact that you are interested in games for their narrative possibilities. The games you really like are the narrative games. What I was wondering about was how game design involves more than the story being told; it involves well-planned interfaces between player and game world. Maybe where art exists in games is not in how well it creates a narrative arc, but instead in the design itself.

I agree totally. The story in games is never going to be as good as the stories in novels or films because, as Clint Hocking says in the book, the nature of drama is authored. And as Jonathan Blow says, “Interactivity sabotages the way successful stories are told.”

Now, I agree with the spirit of what Blow is saying, but I disagree in that interactivity sabotages the way currently stories are told. And I think the challenge for really thoughtful game designers is going to be how to tell a story in an interactive mode that is as interesting, surprising, and fulfilling as the way an authored story is told, and in a way that is native to the way games operate—the systems, the interface, the gameplay.

Maybe I focus too much on the narrative stuff in Extra Lives, but I’m much more interested in the way gameplay feeds into the narrative because, as I say somewhere in it, a game with a great story and shitty gameplay is never going to be a good game. But a game with a stupid story and good gameplay can be a good game. For me as a literary person, that is the most suspect thing about the game form.

Reading the book, I started to think about Portal, which I think is one of the most brilliant games I’ve ever played. And the story in Portal—

There isn’t one.

Yes, there really isn’t one. There’s humor, there’s the funny voice, the computer who is leading you around. But what Portal does so very well is that it teaches you how to play it. And as it gets more and more complicated from room to room, you get better and better at those increasingly difficult tasks. It’s all gameplay. And to me, that seems like art because of the depth of what’s going on. There’s depth in a narrative, and there’s depth in interacting with a system.

Yes, there really isn’t one. There’s humor, there’s the funny voice, the computer who is leading you around. But what Portal does so very well is that it teaches you how to play it. And as it gets more and more complicated from room to room, you get better and better at those increasingly difficult tasks. It’s all gameplay. And to me, that seems like art because of the depth of what’s going on. There’s depth in a narrative, and there’s depth in interacting with a system.

The narrative story is a space that you are allowed to fill in yourself. Very cunningly, they provide you with all the devices—they give you an antagonist, they give you the world, they give you the situation—all that, I would argue, is narrative. Very cleverly hidden narrative. I love Portal, too. I wish I had written about it more, but I felt like that game had been written about so much that I didn’t have anything else smart to say about it.

I wrote about Fallout 3 in the book, and in that game you watch your dad suffocate and die. And I felt absolutely nothing emotionally at that moment, and yet, there are lots of places where I’d wander around the wasteland and I’d find a dead body in some cave, and I didn’t know how it got there, but there would be a note. And that to me was more affecting because I found it. I wasn’t told to go there. It was just something I happened upon.

It’s similar to Portal in that the story that becomes meaningful to you is the one that you just stumble upon. And I think that’s the kind of storytelling that games have to focus on. There are great narrative games, but I think they are essentially a kind of dead end. There will still be great games that adhere to that design model, but I think we already know how good the narrative model can be; I think we haven’t yet seen how good the still evolving, interactive model of games can be.

Fallout 3 was actually the first game I bought for the Xbox 360, and I loved it. Maybe it’s just that it was the first game I played with a fairly deep “sandbox,” and I like the sandbox model [in which players are allowed roam freely through an open-ended game world] a lot. I had this experience where I found Dogmeat—the dog you pick up at the junkyard who follows you around—and when Dogmeat died, when I wasn’t able to protect him when he chased after a Yao Guai [mutant bears that wander through the game’s radioactive Washington D.C.], and when that happened, I pressed pause, I sat down for a second, and I was pretty sad. My dog was dead. Whereas dad dying was, yeah, not as powerful.

Yeah, well, you found Dogmeat. The game made you track down your dad. You weren’t as invested in it. When Trisha [Bissell’s girlfriend] played Fable II and Lucien shot the dog, she started crying. She was shocked. She made a sound, and I looked over and she had tears in her eyes. [One of the options at the game’s conclusion allows players to bring some characters back to life.] And, of course, she brought the dog back from the dead at the end, and I didn’t in my play through. And I stopped playing Fable II, because there was no dog. I brought back all the people I’d killed—I don’t know why I did that. Feeling particularly generous that day.

As far as a focus on narrative game in Extra Lives, I think if it gets any critical hits from game people it will be on that point. I have one game writer friend who always knocks my taste as being really mainstream, and I’m like, when you get dissed or out-snobbed by game people, there’s something really humiliating about that.

“Mainstream? I have Werner Herzog over there.” [Interviewer points to Bissell’s DVD collection.]

“Mainstream? I have Werner Herzog over there.” [Interviewer points to Bissell’s DVD collection.]

Just because I like to shoot zombies.

I’d like to talk about one more thing that I think is really interesting. Last year at GDC there was a talk given by the woman Jane McGonigal, who is kind of the maven of alternative reality and internet games. I went to her talk and realized that it was totally fascinating, but I personally had no interest in what she was talking about. I could recognize that, objectively speaking, this was a brilliant person but her games are about cooperation in systems and people coming together to achieve some kind of salutary social thing, and I realized that what you are interested in in life is probably what you be interested in in games. There’s no dividing between the two. So the games that I play are typically chaotic, really violent, morally ambiguous. The games that I really respond to are the ones that have taken chaos and my role in it, and thrown some curveball at me, like, “Hey, you might not be the good guy. You may be charging or may not be charging up the mountain to plant the flag and if you are, it may or may not be a good thing.”

And you’ve read my stories—they’re all about violence and ambiguity. What you are interested in in real life is the same set of interests you take with you into games. I’m not interested in cooperating in games. It has no appeal for me.

Except for Left 4 Dead?

Well, that’s cooperating under duress. And I like playing Left 4 Dead with friends, but I’m not so crazy about playing it with strangers, even though a lot of people I know who like the game say that’s really the best way to do it because it reveals your true nature.

That was a very important realization for me to have. I was allowed to be interested in shoot-em-ups because I am interested in war. I wrote a whole book about my dad being in Vietnam partially because I’m fascinated by what that experience did for him. And I’ve gone through about eight- or nine-hundred digital wars myself.

We should talk a little bit about some of the games you didn’t get to write about for the book. And one of them in particular that I loved was Shadow of the Colossus. Why does that game work, do you think? There’s almost no dialogue. There’s only a little bit of story to it.

I think that was the first game to really step out of the reigning paradigm of games in the modern era. I think Resident Evil did that a little bit, but I think Shadow of the Colussus stuck its thumb in the eye of every convention of game design.

That world was beautiful. It was so lonely and atmospheric. It was sad. I just think it’s a perfect example of a game, like Portal or Left 4 Dead, that gives you just enough of a frame to have an experience inside. The experience didn’t feel dictated—even though, obviously, all game experiences are dictated. The trick is hiding that, and allowing you to feel like you are having this unique experience, and no one else has played this game this way. Grand Theft Auto IV does that for me, Far Cry 2 does that for me, and Shadow of the Colossus was the first game to make me feel like I wasn’t really playing a game. I was having an experience. I wanted to write about that. I had a chapter on it, but it felt like a lot of wanking. It was all about how lonely and sad everything was. It’s kind of hard to write about those things. I’ve been thinking about playing it through again. There’s one monster with a particularly sad look to him, and I didn’t really want to kill it. He’s a beautiful, hulking thing and I wanted to let it live, but the game makes you kill him.

I know you love Grand Theft Auto IV. Is it bad that my problem with the game is that I couldn’t get more tattoos, outfits, or haircuts like in GTA III: San Andreas? That was sort of my favorite thing about San Andreas, how incredibly customizable the character was. I started Grand Theft Auto IV, and I’m enjoying it, sure, but I can’t get a different haircut?

I know you love Grand Theft Auto IV. Is it bad that my problem with the game is that I couldn’t get more tattoos, outfits, or haircuts like in GTA III: San Andreas? That was sort of my favorite thing about San Andreas, how incredibly customizable the character was. I started Grand Theft Auto IV, and I’m enjoying it, sure, but I can’t get a different haircut?

You’re not the only one who feels that way. Clint Hocking told me the same thing. He thinks GTA: San Andreas is the greatest GTA game ever made and he just didn’t like all the restrictions placed on you in GTA IV, but I never finished San Andreas. I think that there was just too much for me to wrap my mind around. I think they wanted to uphold the integrity of Niko [the main character in GTA IV], in a way. Like, when CJ [the main character in GTA III: San Andreas] shows up to some gang-banger meeting in his underwear and a giant afro, there’s something so absurd about that and I think with the spirit of that game, they didn’t mind. But with GTA IV, they were taking the themes of the game seriously enough to not want Niko to show up wearing a chicken costume to talk to someone. I can respect that decision. I probably would’ve made it, too, if I were trying to make that game.

And there’s a game whose story I think is totally overrated. I mean, it’s good for a game. When I hear people talk about well written games, and they throw out GTA IV or Assassin’s Creed II as work that can stand beside any Hollywood film, I just wonder what fucking planet they’re on. Heavy Rain, too. I read a review on IGN [a videogame review site] that said it would not look out of place in David Fincher or Martin Scorcese’s oevre, and I was like, are you fucking kidding me? I just think there’s so much wishful thinking on that topic for most people.

After taping this interview with Tom, I have since gone out and invested in a used copy of Left 4 Dead for my Xbox 360. But months ago, I cancelled the internet service in my home—to encourage myself to write more—and can only play it on my own. Without the cooperative element, the game is fun, but the few hours I’ve put into it (my zombie kill count is up to about 10,000) pale in comparison to that afternoon playing with Tom.

I startle the witch every time. And it just isn’t the same.

————————————————————————

Buy a copy of Extra Lives here.

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

“Happy Rock” by Matthew Simmons

N. Katherine Hayles’ Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary