New Poethic Folk Cultures of John Cage Go Large

02.03.11

“The vision Cage has perceived is the vision of the craziness that so often enriches our lives, the positive side of the unpredictable. That is what he shares with us…” – Dick Higgins

“The vision Cage has perceived is the vision of the craziness that so often enriches our lives, the positive side of the unpredictable. That is what he shares with us…” – Dick Higgins

“… a practice of reading that enacts a tolerance for ambiguity and a delight in complex possibility. Imagine what might happen if such a practice were to become widespread.” – Joan Retallack

Still trying to hold in mind the experience of viewing Every Day is a Good Day, the show of John Cage’s visual art, first seen at BALTIC in Newcastle last summer, and now touring the UK. Or, rather, keep some memory of the show in dialogue with the reproductions in the catalogue; hold to its distinctiveness whilst seeing it alongside Cage’s music and writing; unfold its specifics without losing sense of the contemporary. A relationship to Cage in 2011, as always, is a shifting, complex thing.

The show itself has developed its own strategies for negotiating between process and object, the somewhat occasional role of visual art in Cage’s practice and the central focus such a monographic exhibition bestows. As conceived by the artist Jeremy Millar, it has adopted Cage’s own structure, developed for Rolywholyover A Circus at MOCA, Los Angeles in 1993, of a “composition for museum” that sought to ensure no two visits encountered the same exhibition.

For this more measured version of the same philosophy, all available works have been gathered, but the show – one of the Hayward Touring projects visiting UK galleries outside of London – will occupy widely diverse spaces. So individual sites choose how many works they can show, then use a pre-devised system to determine how the show will be hung. Variations are also made once the show has opened, both to works shown and positioning.

At BALTIC this involved an orchestration within a single gallery in the large spaces of the former flour mill. At Kettles Yard, Cambridge – and subsequent venues – multiple rooms are required. Whether this chance-led hang is the right strategy is hugely questionable. In music, for example, Cage was notoriously frosty towards those who approached his scores with a sense of freedom that ignored the specificity of the work. In a quote repeated several times in the catalogue, he says:

I use the I Ching whenever I am engaged in an activity which is free of goal-seeking, pleasure giving, or discriminating between good and evil. That is to say, when writing poetry or music, or when making graphic works. But I do not use it when crossing the street, playing a game of chess, making love, or working in the field of world improvements.

I suspect retrospective exhibitions may fall into the second category, between making love and world improvements. Maybe then, a critical response to this show has to focus on two elements: the exhibition as circus and the exhibition as retrospective, the later offering the first chance for an overview of Cage’s visual work. In treating these two categories as separate I hope to discover how they combine, offering both an insight into Cage’s work more broadly and an indication of why his legacy remains so potent.

The exhibition as “circus” creates an experience with some distinct characteristics. At BALTIC I made a list:

The exhibition as “circus” creates an experience with some distinct characteristics. At BALTIC I made a list:

PERCEPTION Cage quotes Rauschenberg that ‘art should have the dignity of not calling attention to itself; it can only be seen if you really look at it.’ Hung by chance, the works here certainly have an autonomy, and I have to adjust to what it is possible to see of them. Some, stuck up high near the ceiling, can hardly be seen at all.

CATEGORIES come into play, particularly when everything is in one large room. Affinities can be noted and links made across the exhibition, be it of size, detail, or absence of detail. Such aesthetic interconnections take precedence over any chronological or art historical readings.

WHOLE Even when the exhibits are split between rooms, Millar’s strategy makes us very aware of the different wholes of the exhibition as something we navigate within, physically and conceptually. The whole of Cage’s visual work (not all of which will be displayed); the whole of his artistic practice (referenced through archive materials, that at BALTIC included an installation of his 1969 multimedia piece HPSCHD).

JUDGEMENT For Cage, once a procedure has been decided upon, it is enacted, without personal preference intervening to determine the outcome. Exhibition as circus asks the viewer to also occupy this position, valuing equally what is felt as resonance and lack. The aim is experience not discrimination. Even so…

Other factors emerge through this show and its informative catalogue that elucidate the Cage phenomenon. The first is Cage’s particular relation to Zen Buddhism. Cage never adopted Zen practices of meditation, but adopted Zen techniques for his own compositional purposes, believing that he attained the same end state.1

Secondly, Cage’s musical scores have themselves often been exhibited as visual art works, never more so than recently with The Anarchy of Silence: John Cage and Experimental Art (at MACBA 2010, now touring). Only one piece in Every Day Is A Good Day also functions as a musical score. The rest have propositions to make informed by their status as non-score and a freedom from that requirement to be interpreted and performed.

–––––––––

1. See John Cage, ‘An Autobiographical Statement’, in Southwest Review, no.76, Winter 1990, 59-76.

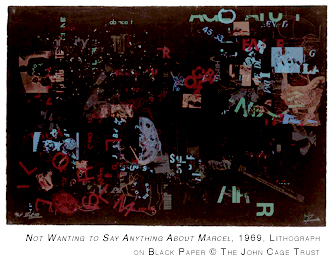

At the Cornish School in Seattle in 1938, Cage befriended Morris Graves and Mark Tobey. When Cage moved to New York in 1942 he stayed with Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim, in whose apartment he first met Marcel Duchamp. At Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Cage met Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

At the Cornish School in Seattle in 1938, Cage befriended Morris Graves and Mark Tobey. When Cage moved to New York in 1942 he stayed with Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim, in whose apartment he first met Marcel Duchamp. At Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Cage met Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

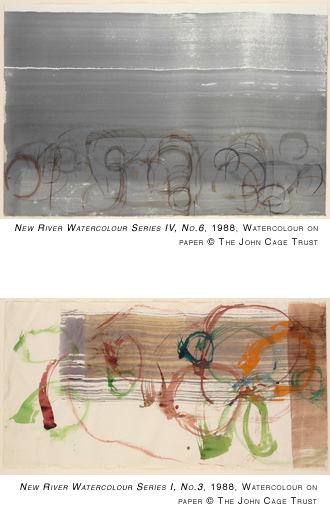

In terms of Cage’s own visual production, Every Day is a Good Day focusses on two distinct relationships towards the end of his life: the prints produced at Crown Point Press in California, and the drawings and watercolors unfolded out of summer workshops at Mountain Lake Workshop in Southwest Virginia.

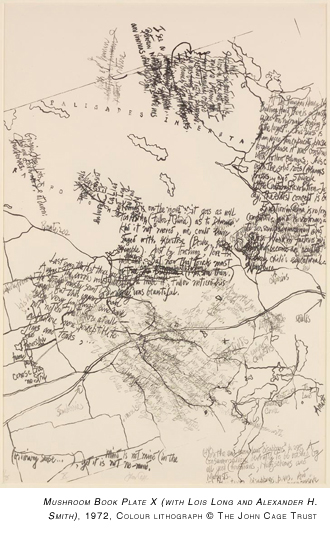

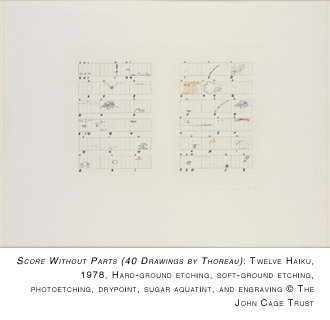

Cage first went to Crown Point Press in 1978, when he was sixty five years old, after an invitation from press founder, Kathan Brown. Brown relates how Cage arrived with a score (incorporating drawings from the journals of Henry David Thoreau) that had taken him from music into “paying attention to how things are to look at.”2

For Cage, who insisted he could not draw, the way to start exploring looking was to try different techniques of print making with his eyes closed (an exercise he attributed to Mark Tobey). Brown tells Millar: “If he was not a visual artist when I invited him, he quickly became one.” At Crown Point, Cage worked on series that followed a distinct structure: begin with an idea, test it to get an idea of what it would look like, then codify the methods to be followed. Once this stage had been reached, projects would be completed.

For that first project – Seven Day Diary (Not Knowing) (1978) – Cage, eyes closed, added and removed engraving techniques throughout the week, after using chance methods to determine where on the paper the image would be placed. The result was seven prints, each containing a rectangle, square or bar shaped swatch of varying proportions, filled with dense scrawl and varying color.

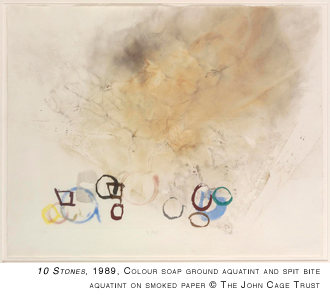

For Where R=Ryoanji (1983) the idea was to imitate the Japanese Ryoanji rock garden by drawing around fifteen stones. The I Ching was used to resolve questions of tools, colour, length, and placement. Such questions were complex and numerous enough to necessitate the creation of written scores, which Cage and his assistants could interpret. Delicate and skeletal engravings built up into prints filled with dense, black, drypoint tangles.

As for Mountain Lake Workshop, Cage was originally invited to Virginia in 1983, to lead mushroom hunts in the Appalachian mountains. Ray Kass, who established the workshop, had discussed with Cage his work at Crown Point, particularly the stone practice he had developed for Where R=Ryonaji. Cage spent time collecting flat stones from the New River, and Cass wondered if these might be the basis of painting practice. Cage said he was too unfamiliar with the watercolor materials to know how to proceed.

–––––––––

2. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations in this essay are from Every Day is a Good Day: The Visual Art of John Cage (Hayward Publishing, London, 2010)

As with Crown Point, Cage’s visual work emerges out of both the initial invitation and the careful provision of space, tools, and assistants. Kass describes surprising Cage with a ready-studio practice, which succeeds in providing Cage with a structure within which he can begin to work:

As with Crown Point, Cage’s visual work emerges out of both the initial invitation and the careful provision of space, tools, and assistants. Kass describes surprising Cage with a ready-studio practice, which succeeds in providing Cage with a structure within which he can begin to work:

It included an ample floor space covered with soft particleboard, and sixty or more river rocks gathered from the New River site the previous day, now numbered and divided into size groups of small, medium and large. I provided a large selection of watercolour brushes, each numbered and arranged according to type and size, a selection of different kinds of rag papers, a palette of about twenty-six colours, additional tubes of paint and various containers for mixing paint. After a brief demonstration of brushes and paint qualities, I encouraged him to ‘experiment’ by painting around some stones on several ‘practice’ sheets of bond paper, which he appeared to enjoy.

This enables Cage to develop a program for painting, combining Kass’ studio with his own computer generated pages of random numbers based on the I Ching. Cage produced over 120 watercolors through eight years of visits to Mountain Lake, each visit’s work developing out of the extensive studio preparations organized by Kass.

Cage’s work with stones has a potential proximity to the kind of expressive gesturality his work generally avoided. As Roger Malbert notes in his catalogue essay, watercolour “lends itself dangerously to spontaneous gesture.” Yet one of the insights of Every Day is a Good Day is to precisely question that reading of gesturality, or how it relates to any straightforward distinction between self––or impersonal expression. As New River Watercolors Series I (1988) indicates with its smooth strokes and circles of color, an advancing gestural complexity can also measure an increase in methods of constraint.

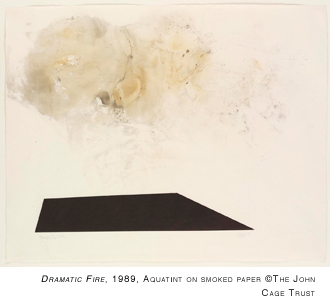

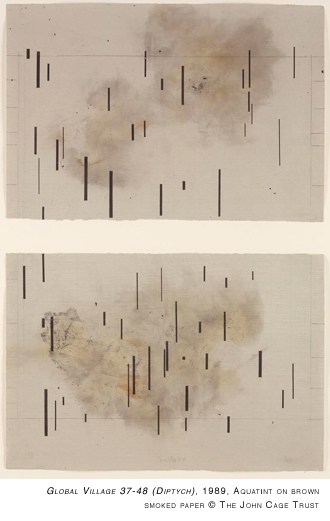

Negotiating these issues, Cage developed a further set of techniques: a preference of feathers over brushes, specially made brushes, and smoke stained paper. Kass describes how the feather had a particular importance for Cage. The most revealing aspect of Kass’ recollection, however, is how this required the exploration of many different types of feathers used as brushes, rather than the continued use of one particular feather.

At both locations, then, Cage’s visual work came from invitations that didn’t specify a particular goal and could allow a cultivation of Cage’s interest in “non-intention.” Both are also linked by Cage’s work with stones. This expands, as Brown notes, to encompass different tools, stone sizes, paper sizes, and color palettes. It includes techniques he developed for other series, like working with fire. Cage developed a portable studio of stones and a practice that involved a stone placed by chance on a piece of paper and a single brush stroke around it. Later, the scores of Cage’s Ryoanji music contained the drawn edges of stones. As Cage remarked. “Music doesn’t go in a circle.”

Through highlighting its own curatorial strategies, Every Day is a Good Day suggests decisions undertaken in the act of revealing the ideas and assumptions that lead such work to be instigated.

Through highlighting its own curatorial strategies, Every Day is a Good Day suggests decisions undertaken in the act of revealing the ideas and assumptions that lead such work to be instigated.

Such assumptions include the artist’s sense of position in the world. In a story told to Millar by Laura Kuhn, Cage’s former assistant and now director of the John Cage trust, Cage is writing his Norton lectures using the I-Ching to write through source texts, including Thoreau. Merce Cunningham suggests the talks would be more topical if they involved material from The New York Times. Cage agrees, and for the next few days clips articles from the newspaper. One day Kuhn finds him weeping and unable to work. He asks her: Do you know about these crack babies?” Kuhn tells Millar:

I had to come to terms with how this person, whom I revered more than anyone in the world as a kind of life coach, could be so ignorant of current affairs… I began to wonder whether what we might reasonably consider the weights of the world, and I would include crack babies in this category, were unusually heavy on him. That letting them in, so to speak, engaging with them, on any level, paralysed him, making him question the viability of his work as an artist, making him wonder whether his work wasn’t in some very real sense futile.

Such an idea of the artist can be applied to the exhibition itself as a fragile structure, vulnerable to the everyday tumult beyond its walls. This runs contrary to the more dominant contemporary sense of the museum as a place of participation, but Millar’s conception unfolds some positive implications of Cage’s simultaneous presence and removal. Kuhn also notes a public lecture where Cage, challenged on his lack of direct political involvement, is initially speechless, before observing he “just wanted to put something positive forward.”

Secondly, Cage’s exploration of a totally different media might have led to or resulted from some kind of artistic crisis. In fact, the only problems of any kind that are evidenced here are to do with Cage finding time for trips to Mountain Lake in his already busy schedule. Nonetheless, a sense of crisis due to a proliferation of creative possibilities is evidenced in a number of Cage’s fellow travelers, such as artist/ composer/ poet/ Dick Higgins.

Higgins suffers a nervous breakdown early in his career due to a sense that he had to choose between art forms.3 Higgins critical formulation of a concept of “intermedia” is one response to this crisis, but more relevant here is how, later in his life, Higgins makes the following formulation to Nicholas Zurbrugg:

Higgins suffers a nervous breakdown early in his career due to a sense that he had to choose between art forms.3 Higgins critical formulation of a concept of “intermedia” is one response to this crisis, but more relevant here is how, later in his life, Higgins makes the following formulation to Nicholas Zurbrugg:

I would say that I am indeed a composer, which is actually where I began, but that I compose with visual and with textual means. That’s a fairly accurate way of describing my approach. A composer is apt to work with more design in his approach than a prose writer, or a poet, or a visual artist, is apt to do. That is, the composer maps out the architectonics of a musical work. And that basic approach is the one I’ve carried on over all the areas that I’ve investigated.4

This recalls the definition of poetry, Higgins notes, Cage gave to his students: “the principles of music applied to language in space.”5 Cage is still a composer, of course, but Higgins’ articulation is a useful way of understanding what carries across and remains distinct in these different areas of his work.

Engraving, Cage observed when Brown videotaped him at work, required a calmness that was the calmness he had been seeking in his music. For Cage “the nature of the difference between graphic work and the musical work brought about a change of feelings. At least gave me new experiences.”

Finally, Every Day is a Good Day makes evident what Joan Retallack has termed a “poethics of a complex realism”:

The poethics of this poem invites a practice of reading that enacts a tolerance for ambiguity and a delight in complex possibility. Imagine what might happen if such a practice were to become widespread. Cage believed that such an eventuality could have real social consequences – that it could, as he said, change the political climate. An ethics, even a poethics, is not a politics, so this question is very much at large. At large is precisely where we need to be.6

–––––––––

3. Higgins discusses this breakdown in the essay “On Doing Too Much,” in his collection A Dialectic of Centuries: Notes towards a Theory of the New Arts (Printed Editions, New York, 1978), 104-109.

4. Dick Higgins, in Nicholas Zurbrugg ed. Art, Performance, Media: 31 Interviews ( University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2004), 211.

5. Dick Higgins, Modernism Since Postmodernism: Essays on Intermedia (San Diego State University Press, San Diego, 1997), 115.

6. Joan Retallack, The Poethical Wager (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2003), 221.

This is how Joan Retallack understands a section of Cage’s “lecture-poem” I-VI (1990). To apply this back to specific works in Every Day is a Good Day, is to realize the specific acts that any poethics is mediated through – the Thoreau drawings that provide a starting point for the Déreau series (1982), for example, or the smoked paper (prepared using straw, whose produced variegated color and left their imprint on the paper) that is the basis of River Rocks and Smoke (1990).

Unlike I-VI the visual works of this exhibition are not intended as performance scores. In this quality of non-score, artist and viewer become separated, each with very different experiences of the work and the freedoms it makes possible. Few viewers are likely to approximate the time consuming process of tossing coins the I Ching requires, even via the computer version (IC) Cage used from 1984. Millar’s strategy holds us closer to Cage the more we understand it, moving the works back within an idea of the processes by which they were made.

*

During his life, as Kyle Gann observed in a Village Voice obituary, “his significance as a composer was overshadowed by his value as a person.”7 For those coming to his work since his death, Cage becomes a one man folk culture. Followers know the sacred texts – there was once a man in an anechoic chamber… – almost as their own. I’m writing as an adherent here.

Within this micro-culture, Cage’s music, writings or art work can disappear behind the stories he told as lectures, performance and in conversation, sometimes again and again. Story Cage relates in contradictory ways to Composer Cage, sometimes enacting some Zen core of that practice, other times concealing its complexities.

More so than with his music or writing, the openness of Cage’s visual works – the smooth feather line following the contour of the rock – alongside some very evident technical procedures – lets them occupy and reveal both aspects of Cage. Compared to viewing his musical scores in an exhibition, there is less sense here of something to interpret, no necessary dividing of viewers into musicians and non-musicians.

–––––––––

7. Kyle Gann “Philosopher No More: John Cage (1912-1992) Quietly Started a Spiritual Revolution)” in Gann Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2006), 296.

Here, then, as a sort of conclusion, is an attempt to respond (sometimes once again) to works in the (remembered) Every Day is a Good Day, in a manner consistent with what this essay has put forth.

Here, then, as a sort of conclusion, is an attempt to respond (sometimes once again) to works in the (remembered) Every Day is a Good Day, in a manner consistent with what this essay has put forth.

(1) Where R=Royoanji are pencil drawings around stones placed at chance determined points on Japanese handmade paper. Begun in 1983, they follow closely on a series of drypoint prints exploring the same territory. As Brown observed of working with Cage, it was the specificity of his practice of asking questions, rather than the aspects of indeterminacy and chance, that were most striking.

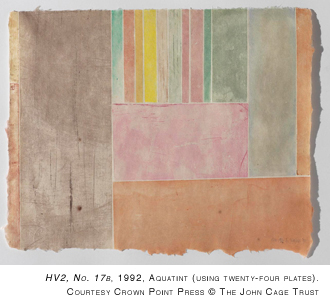

(2) After making three highly complex print series, Cage produced HV (1983). These were made by ink rolled in relief on one of four materials: foam, felt, batting and jute. Chance operations were used to determine placement, color, density of color, and the number of passes from the ink roller and the pressure setting of the press.

No.7 comprise two blue and one red strip of varying textures going horizontally across the paper. Compare to Cage’s drawing blindfold, where impersonality becomes a heightened difference not a reduction or removal of sensory experience.

(3) Where There Is Where There – Urban Landscape (1987-89) was a series Cage recalled, a year after completion, because it seemed too like wallpaper. He added small, black, chance-positioned rectangles. In Signals (1978) the single impression of a print was sold in a package with the plate and other preparatory materials.

In a late series, HV2 (1992), selections of copper from the studio scrap pile were inked and then placed on the press bed. They were etched lightly so fingerprints and other marks from handling caused lighter areas in the final print.

*

Writing about Cage, like curating exhibitions of or on his work, poses challenges. As Millar does with this exhibition – and as Cage himself did in his essay Jasper Johns: Stories and Ideas – I wondered whether to define a structure for proceeding that would form the process of writing and editing. I decided not to, thereby aligning such essaying to Cage’s list of love making, world improvements, and crossing the road.

This creates a writing that appears to stand back from its subject, but also one that knows it has a different, more specific function to fulfill, at least initially. As Every Day is a Good Day reveals, such moving away may actually be a way of attaining proximity, like taking the music class off into the wood to look for mushrooms, or somehow finding some on the streets of Manhattan.

–––––––––

Every Day is a Good Day is at the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, Glasgow 19 February-2nd April 2011, and at the De La Warr Pavillion, Bexhill on Sea, 16 April-5 June 2011.

David Berridge curates verysmallkitchen.com