The Invisible Dragon Redux: La Chanson de Dave

27.07.09

Even in this revised version, augmented by a new essay that traces the pagan uses of beauty in the West, The Invisible Dragon takes the chansons des gestes as its genre, folding metered rhyme and blocky stanza into luminous prose. Although told in a voice that splits the difference between poststructuralist bookworm and gonzo journalist, while easily surpassing both types, the book’s narrative couldn’t be more traditional and threadbare: a lone outsider, surveying the beautiful things that bloom in his midst, takes a stand against the powerful and evil Order that wants to squash them. The evil Order is the Therapeutic Institution – “a loose confederation of museums, institutions, bureaus, foundations, publications, and endowments.” (p. 53) It’s agenda: “…it upholds no standards and proposes no secular agendas beyond its soothing assurance that the ‘experience of art,‘ under its politically correct auspices, will be redemptive––an assurance founded on an even deeper faith that ‘art watching‘ is a form of grace that, by its very nature, is good for both our spiritual health and personal growth––regardless and in spite of the crazy shit that individual works may egregiously recommend.” (p. 53) Perhaps a benign agenda that of the Therapeutic Institution in light of the truly horrific schemes of both the Middle Ages and our own times, except for the fact that it impoverishes our understanding of both art objects and what can happen when we stand before them.

Even in this revised version, augmented by a new essay that traces the pagan uses of beauty in the West, The Invisible Dragon takes the chansons des gestes as its genre, folding metered rhyme and blocky stanza into luminous prose. Although told in a voice that splits the difference between poststructuralist bookworm and gonzo journalist, while easily surpassing both types, the book’s narrative couldn’t be more traditional and threadbare: a lone outsider, surveying the beautiful things that bloom in his midst, takes a stand against the powerful and evil Order that wants to squash them. The evil Order is the Therapeutic Institution – “a loose confederation of museums, institutions, bureaus, foundations, publications, and endowments.” (p. 53) It’s agenda: “…it upholds no standards and proposes no secular agendas beyond its soothing assurance that the ‘experience of art,‘ under its politically correct auspices, will be redemptive––an assurance founded on an even deeper faith that ‘art watching‘ is a form of grace that, by its very nature, is good for both our spiritual health and personal growth––regardless and in spite of the crazy shit that individual works may egregiously recommend.” (p. 53) Perhaps a benign agenda that of the Therapeutic Institution in light of the truly horrific schemes of both the Middle Ages and our own times, except for the fact that it impoverishes our understanding of both art objects and what can happen when we stand before them.

Against the paladins of the Therapeutic Institution, Dave Hickey casts himself as a kind of knowing hidalgo in cowboy boots and a baseball cap, a dog-eared paperback of Coldness and Cruelty stuffed in the back pocket of his washed-out jeans. He strives, against the tide, to keep alive not a world of chivalry but of delirious experience, where desire sets the agenda and all guarantees are off the table. One leaps into the abysses of sex, psychedelics, and intense imagery without legal recourse for the damage that may be done. It’s an unregulated world that unfolds beneath the threshold of protective institutionality––a gambler’s paradise. It’s hardly surprising that Vegas would emerge, in the book that followed this one, Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy, as the one faithful contemporary manifestation of this world in which you take the hits because you know the highs are worth it. And the highs, no one needs to tell you this, are what keep habit and resentment from wrapping you in their tendrils and a kind of deadness from settling deep in your step. The highs are not necessarily good for you, they’re just necessary. They elevate us, even when they drag us through the mud.

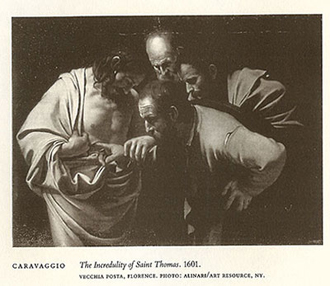

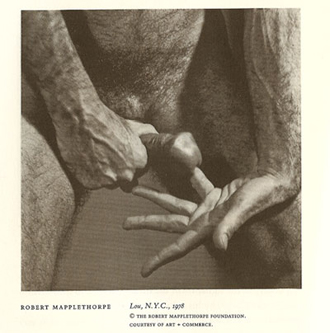

Beauty, in this world, is the rhetorical device potential highs come dressed in, the drag of pleasure and surprise. Beauty is the mediator that can turn “the crazy shit that individual works may egregiously recommend” into imaginable social and existential options. It can doll up toxic assets, airbrush monsters, polish deviance, and make turds gleam like candy canes. It can do this long enough to seduce us into taking a second and a third look, into bending a little our rigid, Puritan parameters. Beauty, in short, can create an audience for what would otherwise pass as unpalatable proposals, like sticking a fist deep in your ass as a form of sublime pleasure. It greases the conduits through which marginal positions can be widely diffused; it lubricates an encounter between thing and beholder with ramifications that are never exhausted then and there.

Hickey’s argument for beauty pivots on shifting the question from What does this or that art object mean? to What does this or that art object do? And, perhaps more pointedly: What does it do to us? It is here that things get complicated for the paladins of the Therapeutic Institution, as Hickey drags in the climate of adult conversation and knowing wager, of equals grown up enough to be able to choose their own poison. The Therapeutic Institution comes off, in this scenario, as willing infantilizer of the audience it supposedly serves. It functions from the premise that the art object owes some kind of moral debt that obliges it to be good to us or for us. Forcing it to function within this economy of obligation, divests the art work of its destabilizing momentum. Effects matter more than purported good intentions, consequences more than proper or improper meanings. It’s a question of how images affect us, how they force us to shake off the calcified habits that we have settled into, how they inaugurate intoxicating new spaces and modes of being and shifts of horizon and invite us to step in or up, always at our own risk.

Hickey’s argument for beauty pivots on shifting the question from What does this or that art object mean? to What does this or that art object do? And, perhaps more pointedly: What does it do to us? It is here that things get complicated for the paladins of the Therapeutic Institution, as Hickey drags in the climate of adult conversation and knowing wager, of equals grown up enough to be able to choose their own poison. The Therapeutic Institution comes off, in this scenario, as willing infantilizer of the audience it supposedly serves. It functions from the premise that the art object owes some kind of moral debt that obliges it to be good to us or for us. Forcing it to function within this economy of obligation, divests the art work of its destabilizing momentum. Effects matter more than purported good intentions, consequences more than proper or improper meanings. It’s a question of how images affect us, how they force us to shake off the calcified habits that we have settled into, how they inaugurate intoxicating new spaces and modes of being and shifts of horizon and invite us to step in or up, always at our own risk.

The “yield of pleasure” that the beautiful image promises is enough to entice us to bond with it and take a gamble on what it proposes. We find at the intersection of its desire to produce pleasure and our desire to find pleasure a momentary clearing from where we feel in communion with the thing not because it is good for us, but because it is willing to make a case for itself in a joyful language of seduction. Delectation, at least for a moment, trumps moral alignment. We enjoy before we identify, and if we can enjoy an image enough we may be willing to identify with things that cast into doubt everything we took, just a minute before, as unshakeable and necessary. Certain pleasures can surprise us into changing our minds and our ways. This is the danger of beauty: it provides the conditions for this operation of dissent.

The art object, in Hickey’s chanson, is always a potential force of contention, a destabilizer of the status quo, a proposal to reconfigure the world. “As a stepchild of the Factory,” Hickey writes, “I am certain of one thing: images can change the world...I know that images can alter the visual construction of the reality that we all inhabit. They can revise the expectations that we bring to that reality and the priorities that we impose on it. I know, further, that these alterations can entail profound social and political ramifications.” (p 34) And this, this unregulated potential to change things, is precisely what the Therapeutic Institution undermines. By determining what is good for us (and sterilizing what is bad), by treating us like fragile bubble kids, it voids the possibility of encountering images that can lead us to overturn everything inside and around us. It protects us from unruly rendezvous that will always seem detrimental from a certain unbending and paternal perspective.

There is something at stake for the art object in this equation as well. The recourse to beauty is a survival strategy for the artifact. Objects seduce viewers, create constituencies around themselves by radiating waves of pleasure-producing sensation. This is done because the object needs these constituencies, the energy that they invest in it, to keep the fog of oblivion from rolling in. Objects survive only when they are talked about, defended, speculated on; only when the record of the enthusiasm they generate grows robust. For even if the object falls out of favor, a victim to one of fashion’s sharp turns, its public performance leaves it available for the salvage operations of dissatisfied future generations. The value of the object is contingent on the amount of heat it can draw from its fan base.

There is something at stake for the art object in this equation as well. The recourse to beauty is a survival strategy for the artifact. Objects seduce viewers, create constituencies around themselves by radiating waves of pleasure-producing sensation. This is done because the object needs these constituencies, the energy that they invest in it, to keep the fog of oblivion from rolling in. Objects survive only when they are talked about, defended, speculated on; only when the record of the enthusiasm they generate grows robust. For even if the object falls out of favor, a victim to one of fashion’s sharp turns, its public performance leaves it available for the salvage operations of dissatisfied future generations. The value of the object is contingent on the amount of heat it can draw from its fan base.

As with all aesthetes worth their salt or their cravats, Hickey’s prose is his own best example. Which is another way of saying that the writing matters here, that it feels almost a matter of principal or necessity that Hickey would pressure and polish the text until it came out a beguiling unicorn to the dead horse that art writing, more often than not, turns out to be. Reading Hickey is a little like reading William Gass or Wayne Koestenbaum: the experience of absorbing the language––as delirious as the writing of it must have been––is such that whatever message it is supposed to deliver either dissolves in the pure joy of reading or leapfrogs our first line of critical defense. What Hickey says often matters half of how he says it. This is something that he has been both praised and castigated for. He’s been described as too talented for his own good, cursed with the diabolical gene that sacrifices argumentative clarity to disarming literary felicity (not true re: clarity, but I can see the prosecutor stumbling over himself to make a case). But this criticism bites mouthfuls of air. Of course the experience of reading the text is important. It’s what has created a constituency of readers, what allows the crazy shit Hickey is egregiously recommending to get through as an option to be earnestly considered, and what justifies, in the final analysis, the reissuing of the book. Unlike the paladins who write as if untainted by the very social and economic mechanisms that pay their rents, Hickey is fully immersed in the game. He wants to generate intense enthusiasm for his product. This is the only way the writing will survive.

Despite how seduced we may be by the pleasure-ride the writing provides, this is the question that continues to peskily pop up, like a goofy dollar-a-game state-fair weasel amid all the jaw-dropping Caravaggio paintings and Mapplethorpe photographs presented as supporting evidence: If the capacity to enfranchise constituencies is what spreads the popularity, cements the prestige and guarantees the continued presence of the artifact, why does the Therapeutic Institution, being so bad for us, have such staying power? What magical card are its wizards keeping close to their chest? And, of course, what they have is what Hickey ignores––the Twentieth Century’s history of broken subjects and tainted objects that went to bat for the wrong team, of sweeping ideological constructions and genocidal policies, of technologies of discipline and nefarious market forces. Subjects damaged by the beauty of brown shirts parading in perfect unison; objects implicated, even if at a distance, in the colonial adventures that generate the capital and labor force that guaranteed the social conditions necessary to leisurely paint nymphs in the garden; massive disciplinary technologies that make the Therapeutic Institution feel like a warm-up exercise. The magic of beautiful objects pales in the grey light cast by these catastrophes. More than draining the life from Hickey’s critique, acknowledging the tragedies of the last turbulent century may help explain why we are not all jumping at the prospect of swapping a more insouciant agenda that pivots on beautiful objects and undamaged subjects, things that give off a whiff of fantasy this late in the game, for the institutionally-underwritten one that demands art objects do their tiny part in counterbalancing the avalanche of lies that coated such a large chunk of the last hundred years in misery.

Despite how seduced we may be by the pleasure-ride the writing provides, this is the question that continues to peskily pop up, like a goofy dollar-a-game state-fair weasel amid all the jaw-dropping Caravaggio paintings and Mapplethorpe photographs presented as supporting evidence: If the capacity to enfranchise constituencies is what spreads the popularity, cements the prestige and guarantees the continued presence of the artifact, why does the Therapeutic Institution, being so bad for us, have such staying power? What magical card are its wizards keeping close to their chest? And, of course, what they have is what Hickey ignores––the Twentieth Century’s history of broken subjects and tainted objects that went to bat for the wrong team, of sweeping ideological constructions and genocidal policies, of technologies of discipline and nefarious market forces. Subjects damaged by the beauty of brown shirts parading in perfect unison; objects implicated, even if at a distance, in the colonial adventures that generate the capital and labor force that guaranteed the social conditions necessary to leisurely paint nymphs in the garden; massive disciplinary technologies that make the Therapeutic Institution feel like a warm-up exercise. The magic of beautiful objects pales in the grey light cast by these catastrophes. More than draining the life from Hickey’s critique, acknowledging the tragedies of the last turbulent century may help explain why we are not all jumping at the prospect of swapping a more insouciant agenda that pivots on beautiful objects and undamaged subjects, things that give off a whiff of fantasy this late in the game, for the institutionally-underwritten one that demands art objects do their tiny part in counterbalancing the avalanche of lies that coated such a large chunk of the last hundred years in misery.

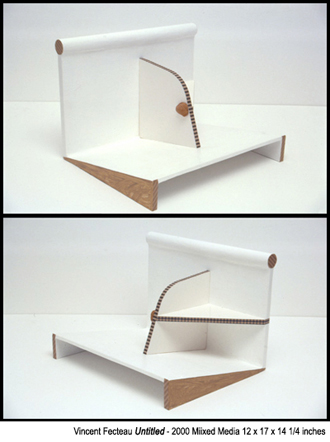

And why beauty exclusively, why this quality so prone to be co-opted not by the residents of the vibrant margins as by those who serve at the pleasure of gloom? Surely, there are other intense qualities in the art object with which it can spear us through the eye and shake us to the core. Someone like Peter Eisenman would argue, from behind his perennial bow tie and graceless prose, that it is precisely the shapes that unmotivate desire rather than fulfill it, shapes that are so strange or unexpected that they may not respond to our needs as much as force us to think beyond them and beyond all the parameters we live by, that really fire up an artifact’s affective power. Weirdness, more than beauty, opens the world to new reconfigurations. Not Matthew Barney’s staged strangeness, mind you, but that interpretation-resistant ineffable quality in Vincent Fecteau’s delicate constructions or the irreducible what-the-fuckness in Ulrike Ottinger’s delirious films. One wonders if Hickey’s position may be open to challenge not from the outraged paladins of the evil Order but from kindred spirits who also like their art objects to royally fuck things up but worry about those who would use beauty to iron-out rather than multiply the strange folds into which the world––and we, its puny and damaged inhabitants––can be bent.

Image 1 is the cover from the book and images on pages 2 (Caravaggio: The Incredulity of St. Thomas, 1601 and 3 (Robert Mapplethorpe: Lou, N.Y.C., 1978 are scanned from Invisible Dragon (2009) as well. The 4th is from Matthew Marks Gallery, NYC