An Interview with Marc Handelman

13.07.06

The viewing experience Marc Handelman creates is not one of comfort – his unsettling work references a history of painting that ranges from the Hudson River School to Abstract Expressionism to Thomas Kinkade, and depicts troubling landscapes, billboards and nationalistic iconography. Neither of these things is particularly chilling in and of themselves, but it is Handelman’s virtuoso handling of light that makes the subject matter take on a dark and sometimes even sinister feel. The result is varied, but always leaves the viewer with an indefinable yet very clear disquieted feeling.

The viewing experience Marc Handelman creates is not one of comfort – his unsettling work references a history of painting that ranges from the Hudson River School to Abstract Expressionism to Thomas Kinkade, and depicts troubling landscapes, billboards and nationalistic iconography. Neither of these things is particularly chilling in and of themselves, but it is Handelman’s virtuoso handling of light that makes the subject matter take on a dark and sometimes even sinister feel. The result is varied, but always leaves the viewer with an indefinable yet very clear disquieted feeling.

During our conversation at his studio, Handelman described the “warm peachy light” of a Sanford Gifford painting as being so disarming that he imagined the feeling might be comparable to lethal injection. It wasn’t until afterward that it occurred to me that M.L. Sheil, a novelist at the turn of the century, had similar ideas. In 1901, he published a book called The Purple Cloud, which tells the story of a man who manages to survive the poisonous aroma of peach blossom brought by a fog that wipes out the Earth’s population. There are countless examples throughout history that show the suspect nature of extreme sweetness, and while Handelman’s paintings are not so singular, they certainly touch upon this idea and reveal its presence within various forms of propaganda. His 2006 painting vision is based on Frederick Church’s saccharine Civil War propaganda painting “Our Banner in the Sky” (1860) and draws upon a contemporary palette commonly used in the fields of advertising, news and even mass produced paintings to illustrate this point. Furthering this idea, Handelman pointed out that “Lichtdom,” created by Hitler’s chief architect Albert Speer, was part of the famous 1937 rally in Nuremburg, and partially inspired “The Tribute in Light” at ground zero in New York City, (a memorial that interestingly showed up in aspects of FOX News billboards, and are inspiration for some of the artist’s paintings).

The influence of artists like Speer came up more than once during my studio visit, and I was left with the feeling that there was much more to say on the subject. The purpose of the conversation that took place over email was to further explore how these influences shape what the viewer sees, and to suss out to what capacity his studio practice informs the paintings.

FANZINE: In your last show at Lombard Fried, the work very often depicted landscapes as some sort of barrier to light. There was a sense that growth was happening all around you, and you had no control over its direction or what it did. They are strange, bittersweet fantasies. In your newest body of work, landscape seems to play a far less dominate role. What prompted the change in your paintings?

FANZINE: In your last show at Lombard Fried, the work very often depicted landscapes as some sort of barrier to light. There was a sense that growth was happening all around you, and you had no control over its direction or what it did. They are strange, bittersweet fantasies. In your newest body of work, landscape seems to play a far less dominate role. What prompted the change in your paintings?

HANDELMAN: I suppose I thought about the paintings themselves as a kind of barrier or void—an obfuscation to some wholly other event. But for me, the light and the darkness are always the same. They both collapse into the same kind of abyss. But I’m less interested in a relationship to nature than in landscape painting as a framework for pathologies and desires about power and space. So “nature” in my work is always a foil. I think the first time I really started thinking about Luminism was when I painted “Soft Ascent”—that execution viewing window and architectural facade. I had initially painted in a curtain, wanting to eradicate the view altogether. Maybe that kind of speaks to that “barrier to light” that you just mentioned, but then I painted it out with this warm peachy radiant light like a Sanford Gifford painting. There’s this feeling in Gifford’s work, of everything just vanishing—the mountains, the trees, the distance and even the viewer. And it’s such a clean annihilation too, not like [J.M.] Turner or [Frederick] Church’s sublime. It’s a dissolution that’s totally disarming and beautiful and I thought maybe that’s the feeling you might have from, say, a lethal injection.

FANZINE: You are obviously thinking about painting and the history of painting quite a bit. You mention Luminism, and your work references the Hudson School of Painting, as well as Abstract Expressionism. I would imagine those who deal with landscape and propaganda are of great interest to you. Do the prints of The Steinberg Brothers have any interest to you? Who else are you looking at?

HANDELMAN: I’m only superficially aware of The Steinberg Brothers. Unfortunately, I missed the show at the MOMA too. I’m always thinking about design, but it’s a much less focused or researched area for me, which is fine. I sort of approach it more intuitively. In terms of structure, I think there’s an interesting relationship between the American Precisionists, and even O’Keeffe’s early city-scape paintings and a lot of early 20th century design work—the Bauhaus and, of course, political propaganda. There’s this fascination with machines, the geometry of modernity, the monumental and especially light. Paul McCarthy has been really important to me for a while, which says very little actually, as he’s so influential. But I’m particularly interested in the relationship between kitsch, monumentality and fascism in his work. I’m also interested in the way McCarthy uses space, its inversions, voids and its disorientating functions. Its kitsch is of such an American flavor too. Kara Walker’s work has also been incredibly influential, it’s a constant model. I’ve also been reading and looking at as much Ruscha as possible. He’s definitely part of my daily thoughts in the studio. But most recently, I’ve been thinking about Riley and Op art. Perhaps there’s this space in the physiological response to an image that has some pretty disquieting implications and ideas regarding the manipulation of agency and rationality in the viewer.

FANZINE: It’s interesting that most of these artists are not painters. Many who are, though, tend to be very philosophical about paint—what it means to them and how it has been used throughout history. Do you have an idiosyncratic relationship with paint?

FANZINE: It’s interesting that most of these artists are not painters. Many who are, though, tend to be very philosophical about paint—what it means to them and how it has been used throughout history. Do you have an idiosyncratic relationship with paint?

HANDELMAN: I don’t know how I would generally characterize my relationship to paint. It’s always been very controlled. I think there’s actually an increasing sense of control with the material even as the more recent work looks looser, or less controlled. There’s a false sense of freedom of many of the forms and that’s really interesting to me.

I’m always asking myself that question about the paint. I mean, you’ve got this gooey stuff with all the baggage of a language that’s fundamentally unfixed but all weighed down. You want to be conscious and critical of the codes and frames that might be externally imposed, but ultimately you want to negate all those restrictions and make your own language.

I’m trying to find a space somewhere between a kind of debased language, like an extreme version of those painters who make the 5-minute sci-fi landscapes in Times Square with tons of short cuts and effects, and one that’s a lot more subtle, one that even contradicts what it sets out to do. Ruscha, even the wholly commercial shorthand of Moran might be at one end, but unlike them, a kind of bodily implication in the materiality is very important. I don’t mean this in its more traditional, rhetorical and gendered terms, but I think it has to do with desire and the extent to which desire becomes externalized, engaged physically. Not ideas about desire, but the impulse to form with your hands, this thing. To construct it out of these little tools that has your body and its anxieties as well as pleasures written all over it. Like how your handwriting changes depending on what you’re writing.

With that recent painting, “Only One,” that’s inspired by the FOX News billboard, it was crucial for me to enter a dimension of that language in the most direct way, and perhaps with the ubiquity of programs like Photoshop, any kind of handmade image takes on an excessive nature. You can’t not be present at any point in its making. The implications for me are about my personal responsibility, agency and a space where things are a lot more unclear, at times critical, but also more insidious.

FANZINE: I feel like I’m not supposed to like these paintings—or at least not be seduced by them but they are like those giant lollipops you get as a kid. They look great, but are ultimately too large to take in all at once. The same is true of propaganda I think. FOX News, Thomas Kinkade—they have the allure of something easy, but the underpinnings are very complex. The trouble is that these things are so complex that it is difficult to fully represent them. Do you feel your work is a complete representation and interpretation of these underpinnings?

HANDELMAN: Well, I think in the examples you give, you get sort of hit on the head, sucked right into the space that’s been designed for just that. I think the way those types of images function is actually very simple. Those images don’t slowly unfold like a Morandi or Agnes Martin or something. Everything is right there on the surface. And you’re not supposed to think when you look at those things. You’re supposed to feel something. And you do. I’m as seduced as anyone else, maybe only I’m creeped out at the same time by it. I don’t think I’m trying to represent some hidden dynamic or anything in an analytic way. I, too, want to create very emotive work. I’m not outside of the problem so to speak but that’s a more interesting and real position to be in. Andreas Hyussen, in this essay called “Monumental Seduction,” has this great quote from Foucault who writes about “the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us” (Hyussen, Present Pasts, P. 39. 2003). I think about that idea and feeling quite a bit. I’m not sure you’re supposed to like the paintings. I certainly feel discomforted about a lot of what I do.

FANZINE: Your paintings are bittersweet in the same way that Foucault writes about the power of fascism. I think they represent both the success and failure of political structures. They aren’t hopeful in any way, which I find not only a disheartening feeling, but also a rather lonely one. The images you use don’t create a landscape in which dissonance will be heard. To what degree does the current political climate inform your work?

FANZINE: Your paintings are bittersweet in the same way that Foucault writes about the power of fascism. I think they represent both the success and failure of political structures. They aren’t hopeful in any way, which I find not only a disheartening feeling, but also a rather lonely one. The images you use don’t create a landscape in which dissonance will be heard. To what degree does the current political climate inform your work?

HANDELMAN: The current political situation feeds all kinds of feelings and ideas into my work, but none for the purpose of illuminating “information.” I think it’s fueled a great amount of anger, sadness and perhaps most of all paranoia. But the work has always existed in an imaginary space that is however rooted in social and political reality, is about a kind of paranoia, a kind of dream where fantasies are enacted and fears are played out. The work often does aestheticize politics, only to such a degree that its dysfunction can’t be turned outwards; it exceeds persuasion and its power is self-consuming.

FANZINE: There is the suggestion of something faintly religious about this work. Through the landscape, through the light, it is as though there is something larger out there. And though it’s a seductive force, it’s not necessarily a good one. Where do you situate yourself vis-à-vis seductivity versus negativity?

HANDELMAN: Oh there’s definitely a religious or spiritual dimension to the work I make. Religious ideology and faith played such a big role for The Hudson River School, and its predecessors in figures like Caspar David Frederich and Turner. American Christian ideology is, of course, central to the rhetoric of “Manifest Destiny.” The Sublime is really the bracketing aesthetic term of the epoch. But the spiritual dimension to the political and historical developments in 19th century America were part of what made them so diabolical. The historian Barbara Novak wrote that “[t]he taking of the continent was powered by an undisputed Christian consensus, a missionary zeal, a largely benign interpretation of progress. The themes are contradictory: the growth of a comfortable middle class and an ongoing Indian genocide; the idealization of nature concurrent with industrialization; confidence in an inevitable future and a selective memory of the past.” (Nature and Culture, P. xii) So I’m always thinking about the emotive and aesthetic forces that marshal ideas and actions, and light has always played such an important role in that.

This spiritual connection to ideology is also an intrinsic part of fascist psychology. Speer’s “Lichtdom” at the Nuremberg rallies was also meant to instill feelings of a transcendent order and national destiny. I think this idea of losing yourself in the seduction and beauty of something is really remarkable and terrifying. Mike Kelly talks about the relationship between fascism and the sublime, of the loss of the self and the potential annihilation of the self to this larger entity. Perhaps too, we could say the same thing of the televised experience of the “Shock and Awe” bombing campaign. Throughout all these things though, there’s this sense of beauty and the orchestration of positive forces. One of the challenges for me has been to tease out this dark side from a space that always feels really good and that’s always light.

Marc Handelman lives and works in New York. He is represented by Sikkema Jenkins Gallery, and will be in the upcoming show “USA TODAY” at The Royal Academy of Arts in London, October 4th, 2006, and “This ain’t no foolin’ around” at the Letterkinney Art Center in Letterkinney Ireland, July through August.

Image Notes:

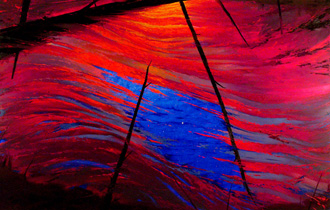

Gorge (detail)

2005, oil on canvas, 47.5" x 36"

Trademark

2006, oil on canvas, 41" x 82"

Only One

2005, oil on canvas, 93" x 168"

Our Banner in the Sky

2005, oil on canvas, 89" x 144"