American Mirrored – Dan Graham: Beyond

23.03.09

The length of the mirrors and their distance from the cameras are such that each of the opposing mirrors reflects the opposite side (half) of the enclosing room (and also the reflection of an observer within the Area who is viewing the monitor/mirror image.)

The length of the mirrors and their distance from the cameras are such that each of the opposing mirrors reflects the opposite side (half) of the enclosing room (and also the reflection of an observer within the Area who is viewing the monitor/mirror image.)

The camera sees and tapes this mirror’s view.

Each of the videotaped camera views continuously is displayed 5 seconds later, appearing on the monitor of the opposite Area.

Mirror A reflects the present surroundings and the delayed image projected on Monitor A. Monitor A shows Mirror B 5 seconds ago, the opposite side’s view of Area A. Similarly, Mirror A contains the opposite side’s view of Area B.

A spectator in Area A (or Area B) looking in the direction of the mirror sees: 1) a continuous present-time reflection of his surrounding space, 2) himself as observer, 3) on the reflected monitor image 5 seconds past, his Area as seen by the mirror of the opposite Area.

A spectator in Area A turned to face Monitor A will see both the reflection of Area A as it appeared in Mirror B 5 seconds earlier, and on a reduced scale, Area A reflected in Mirror B now.1

Dan Graham’s description of his mirror installation piece, Opposing Mirrors and Video Monitors On Time Delay (1974) reads like the TV direction for Siegfried and Roy’s eight-minute multiple illusion farewell performance. The experience of this piece, as well as Graham’s other, mirrored wall and video installations on view at MOCA’s 40-year Graham survey, is somewhat more akin to entering my local (Chase) WaMu bank with its labyrinth of smoked glass chambers and gauntlet of security cameras one must pass through in order to pay your credit card or make a deposit. In Graham’s impractical and much more amusing version, cowed customers standing on-line have been replaced with gleeful museum visitors running from room to room, waving at themselves on closed circuit TV. Mirrored walls reflect viewers’ surroundings and themselves while a television monitor shows what has just occurred in the space––recorded seconds earlier as seen from the opposite monitor.

1. Graham, Dan, Video – Architecture – Television: Writings on Video and Video Works 1970-1979

Seeing one’s self on a time-delayed closed circuit TV has all the inherent creepiness of a scene from a Japanese horror film. Your physical self has just moved through a contained space––you perceived this passage in real time, as well as observed it simultaneously in mirrors. However, seconds later, we witness ourselves going through the motions once more via the “live” video feed. It’s uncanny, like glimpsing one’s own reflection reflected back to us from a second mirror: the view of our face, double-refracted, is rendered eerily unrecognizable from our normal, flipped perspective typically observed in a single mirror. Yet, we are seeing the view of ourselves that others always see in real time and space. With his interest in Lacanian ‘mirror phase’ theory2 as a starting point, Graham tweaks the foundation just enough to make us aware that what we subjectively experience as I remains incomplete; the act of being perceived as well as perceiving is essential. In this way, the artist reminds us the experience of art is also a kind of self-experience that makes profound transformations of consciousness possible.

Seeing one’s self on a time-delayed closed circuit TV has all the inherent creepiness of a scene from a Japanese horror film. Your physical self has just moved through a contained space––you perceived this passage in real time, as well as observed it simultaneously in mirrors. However, seconds later, we witness ourselves going through the motions once more via the “live” video feed. It’s uncanny, like glimpsing one’s own reflection reflected back to us from a second mirror: the view of our face, double-refracted, is rendered eerily unrecognizable from our normal, flipped perspective typically observed in a single mirror. Yet, we are seeing the view of ourselves that others always see in real time and space. With his interest in Lacanian ‘mirror phase’ theory2 as a starting point, Graham tweaks the foundation just enough to make us aware that what we subjectively experience as I remains incomplete; the act of being perceived as well as perceiving is essential. In this way, the artist reminds us the experience of art is also a kind of self-experience that makes profound transformations of consciousness possible.

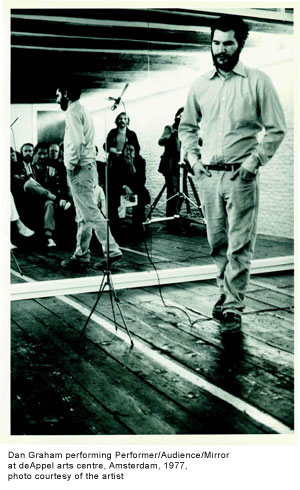

Co-organized by curator Bennett Simpson and Whitney Museum curator Chrissie Isles, Dan Graham: Beyond includes about one hundred works, myriad examples of Graham’s shape-shifting practice: video and video installations, performance documentation, photographs, theoretical texts, architectural models and pavilions. Originally slated for MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary building as a follow up to 2008’s Lawrence Weiner retrospective, the extensive Graham survey was moved at the last minute to the Museum of Contemporary Art’s main building on Grand Avenue after the G.C. was closed due to budget constraints. (The G.C. is officially on hiatus for six months, but could possibly remain closed indefinitely as a result of MOCA’s fiscal crisis – MOCA is currently operating on a shrinking endowment of $20 million with an annual budget of $20 million, meaning the organization could go broke later this year.)

One wonders if, in the old glory days, pre-Economic Crisis and prior to the departure of half of their board, MOCA’s G.C. courtyard may have housed an outdoor installation of one or more of Graham’s pavilions. Still, the last minute switch does not lack a certain serendipity as the looming glass and mirror office buildings of the downtown L.A. skyline, curbside bus shelters, and MOCA’s own reflective glass façade all echo Graham’s pavilions’ architectural associations with the steel and glass Minimal art structures of the modern city.

2. In his ‘mirror phase’ theory, Jacques Lacan writes of the child falsely imagining his body image to be a complete, unified entity. The child sees itself formed as an image in the same way as an Other: the human being who is in the mirror and its body, which is dissimilar to its subjective experience, but identified with it. In its mirror image, the ego appears to be in two places at once, outside itself (in the world of the Other, looking back at oneself) and within itself (looking out at its own image).

Created as ‘microcosms of the architecture of the city as a whole,’ deceptively simple geometric structures built of metal and two-way mirror, plain glass, and/or tinted glass, Graham’s pavilions are optical traps that modify perception and transform the viewer into both surveilled subject and voyeur. When Graham was asked to create a piece for the Venice Biennale in 1976, he aimed to please by utilizing two materials he felt Italians loved, steel and glass, to create Public Space/Two Audiences (1976). The installation exists in a room built with the proportions of a rectangle in the golden mean. A sound insulating glass divider splits the space into two smaller rooms, which sort of resemble showcase windows at a pet store. On one side of the divider, the audience space has a mirror as its far wall. On the other side of the divider, the audience space has a plain white wall. The divider itself also acts as a reflector, a sort of ghost mirror. Conscious they are being watched by viewers on the opposite side, participants become aware of a multitude of reflections. Girl’s Make-up Room (1998-2000), a semi-circular pavilion made of two-way mirror and perforated steel with lipsticks, supplied by the museum, at the viewers’ disposal, is reminiscent of a club in Miami Beach with two-way mirrors facing the Strip. Unbeknownst to the throng passing by, the shift in their postures and attitudes (guys flex, girls suck in their cheeks and fix their bangs) when they catch a glimpse of themselves in the two-way mirror accounts for hours of amusement for the unseen voyeurs inside. Graham’s pavilions, as with his performance and installation pieces, activate the viewer, powering up one’s experience from spectator to participant in the art. In his essay on Sol LeWitt, Graham writes, “There is no distinction between subject and object. Object is the viewer – the art and subject is the viewer, the art.”

Created as ‘microcosms of the architecture of the city as a whole,’ deceptively simple geometric structures built of metal and two-way mirror, plain glass, and/or tinted glass, Graham’s pavilions are optical traps that modify perception and transform the viewer into both surveilled subject and voyeur. When Graham was asked to create a piece for the Venice Biennale in 1976, he aimed to please by utilizing two materials he felt Italians loved, steel and glass, to create Public Space/Two Audiences (1976). The installation exists in a room built with the proportions of a rectangle in the golden mean. A sound insulating glass divider splits the space into two smaller rooms, which sort of resemble showcase windows at a pet store. On one side of the divider, the audience space has a mirror as its far wall. On the other side of the divider, the audience space has a plain white wall. The divider itself also acts as a reflector, a sort of ghost mirror. Conscious they are being watched by viewers on the opposite side, participants become aware of a multitude of reflections. Girl’s Make-up Room (1998-2000), a semi-circular pavilion made of two-way mirror and perforated steel with lipsticks, supplied by the museum, at the viewers’ disposal, is reminiscent of a club in Miami Beach with two-way mirrors facing the Strip. Unbeknownst to the throng passing by, the shift in their postures and attitudes (guys flex, girls suck in their cheeks and fix their bangs) when they catch a glimpse of themselves in the two-way mirror accounts for hours of amusement for the unseen voyeurs inside. Graham’s pavilions, as with his performance and installation pieces, activate the viewer, powering up one’s experience from spectator to participant in the art. In his essay on Sol LeWitt, Graham writes, “There is no distinction between subject and object. Object is the viewer – the art and subject is the viewer, the art.”

Evocative of the steel and glass box houses designed by architects Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, Graham’s pavilions share not only their structure, but a few of the problems or limits of modernist utopian architecture. Adrian Searle wrote about one of Graham’s outdoor pavilions that became so infested with flies and fly poop, to stand within it was like a leisurely interlude inside a Damien Hirst vitrine. Graham’s concern with the relationship between architectural form and function is apparent in pieces such as Alteration of a Suburban House (1978), which takes on the form of a scale architectural model. Impractical, yet founded in architectural reality, Graham has altered a generic suburban tract house by expanding the typical front picture window into an entire wall of glass and then replacing the back interior wall with a mirror that reflects the outside world. The mirror reflects the house’s interior as well as the street and houses across the street, projecting an ongoing domestic sitcom for anyone to see.

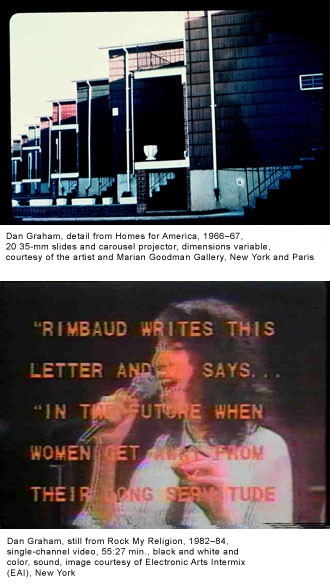

It’s possible to trace Graham’s interest in architecture and the suburban landscape back to his early conceptual work, Homes for America (1966-67). An illustrated magazine article for Arts Magazine made when Graham was 24, the piece consists of short texts and photographs he took with a point-and-shoot Kodak Instamatic camera on train rides home through suburban New Jersey tract housing. Connecting the mass produced, banal repetition omnipresent in suburbia to the works of Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd, Homes for America stands as an ironic, critical commentary on Minimalism. In his essay “Moments of history in the work of Dan Graham,” B.H.D. Buchloh writes of Dan Flavin misapprehending Homes for America as a work of photography along the lines of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Rather, Homes for America established the grounds of conceptualism, a new social art with the city as its prime subject of investigation.

It’s possible to trace Graham’s interest in architecture and the suburban landscape back to his early conceptual work, Homes for America (1966-67). An illustrated magazine article for Arts Magazine made when Graham was 24, the piece consists of short texts and photographs he took with a point-and-shoot Kodak Instamatic camera on train rides home through suburban New Jersey tract housing. Connecting the mass produced, banal repetition omnipresent in suburbia to the works of Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd, Homes for America stands as an ironic, critical commentary on Minimalism. In his essay “Moments of history in the work of Dan Graham,” B.H.D. Buchloh writes of Dan Flavin misapprehending Homes for America as a work of photography along the lines of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Rather, Homes for America established the grounds of conceptualism, a new social art with the city as its prime subject of investigation.

Graham’s examinations of Minimalism, conceptual art, and architecture have had an enormous influence on contemporary art, but it is his obsession with rock ‘n’ roll that has made him a guru to the supercool (Sonic Youth are his BFFs and played a special members-only opening party for the MOCA show). With its jerky edits, staticky lack of tracking, and the low-tech look and feel of an early 80s public TV announcement, Rock My Religion (1982-84) is a mesmerizing hour-long video linking rock ‘n’ roll to America’s puritanical roots and is one of the most compelling pieces in the MOCA survey. A visualization of Graham’s extensive writing on rock music, text scrolls over an acid green, orange, or yellow screen, comparing the “reeling and rocking” of the Shakers’ trance dances with the quaking hips of Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley. A bare-chested, teenaged Henry Rollins convulses onstage, drenching clamoring fans with his sweat while Patti Smith wails, “Shake…shake…shake off your flesh!” With its dream-like succession of images of ecstatic tent revivals and sex-crazed rock fans, Graham posits rock music is the new religion of suburban teenage consumers. Created in the era of Jerry Falwell bawling on TV while asking for your dollars, Rock My Religion’s hallucinogenic meditation has maintained its relevance to an American culture historically steeped in evangelical superstition and ideology. Maintaining his works’ sociocultural concerns, Rock My Religion links us back to Graham’s early text and image piece Homes for America and, wisely, will not be left out of consideration when navigating this comprehensive retrospective.

*title page: Dan Graham, Heart Pavilion, 1991, two-way mirror glass and aluminum, 94 x 168 x 144 in., Carnegie Museum of Art,

Pittsburgh, A.W. Mellon Acquisition Endowment Fund and Carnegie International Acquisition Fund, 92.5, photo courtesy of the artist

**For more info on this exhibition see the Moca website