American Experience: Roberto Clemente

20.04.08

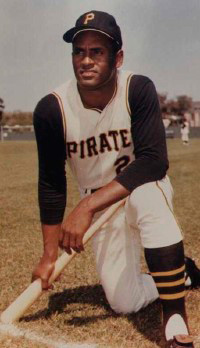

Baseball legend Roberto Clemente might not have run the bases with an economy of motion, but he was certainly fast and most definitely exciting to watch. Legs churning, long arms thrashing the air outside his sleeveless #21 Pittsburgh Pirates jersey, Clemente rounded first base and headed to second with the look of a man driven by both determination and desperation.

Baseball legend Roberto Clemente might not have run the bases with an economy of motion, but he was certainly fast and most definitely exciting to watch. Legs churning, long arms thrashing the air outside his sleeveless #21 Pittsburgh Pirates jersey, Clemente rounded first base and headed to second with the look of a man driven by both determination and desperation.

Highlights of Clemente’s baseball skills are abundant in PBS’s American Experience: Roberto Clemente, which premieres Monday, April 21st. Widely considered a five-tool player (above average at running, throwing, fielding, hitting for average, and hitting for power), Clemente has been called baseball’s first Latin superstar. He is still a dynamic player to watch in the clips that span the 1960’s and reach into the early 1970’s. Of all of this Hall of Famer’s skills, his throws from his position in right field might be the most breathtaking to witness; perfect, low-trajectory strikes to the catcher.

Clemente achieved fame as a ballplayer, but the circumstances of his death in 1972 at the age of 38 say much more about him as a person. A native of Puerto Rico, Clemente was touched by the plight of earthquake survivors in nearby Nicaragua. After hearing that relief supplies were not reaching victims of the disaster, he accompanied an aid shipment aboard a DC-7 heading to Managua, Nicaragua from San Juan, Puerto Rico. The plane crashed into the Atlantic Ocean just after takeoff on New Year’s Eve, and Clemente’s body was never found.

That single humanitarian act, and its result, carry Clemente’s life story beyond the field of most sports biographies. And even though tragedy places a focus on Clemente’s kindness as a human being, there were other dimensions to his personality as well. His pride, passion, and sensitivity were not limited to the baseball field or the act of charity that led to his death. American Experience: Roberto Clemente writer/director Bernardo Ruiz does an excellent job of revealing a man who wasn’t perfect but who possessed a great depth of character and sincerity and who lived a life worthy of remembering.

Narrated by actor Jimmy Smits, the one-hour documentary features interviews with Clemente teammates Manny Sanguillen, Steve Blass, Al Oliver, and Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda, as well as Clemente’s wife, Vera, and brother, Matino. Other interview subjects include Pulitzer Prize winner David Maraniss, author of Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero. Visually, the program offers a satisfying number of filmed highlights from Clemente’s career, in addition to shots and film of his beloved home, Puerto Rico.

Narrated by actor Jimmy Smits, the one-hour documentary features interviews with Clemente teammates Manny Sanguillen, Steve Blass, Al Oliver, and Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda, as well as Clemente’s wife, Vera, and brother, Matino. Other interview subjects include Pulitzer Prize winner David Maraniss, author of Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero. Visually, the program offers a satisfying number of filmed highlights from Clemente’s career, in addition to shots and film of his beloved home, Puerto Rico.

The youngest of seven children, Clemente was born in 1934 in a poor, rural area of Puerto Rico. As a teenager, he would ride the bus to San Juan to watch winter league ballgames. His favorite player was Monte Irvin, the Negro Leagues star who later played for the New York Giants and was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

As Maraniss points out early in the documentary, the racial climate in Puerto Rico during Clemente’s youth was much more relaxed than what he would later find in the United States.

“If you were a black Puerto Rican, or black American, you could eat wherever you wanted to, could sleep wherever you wanted to; you could date whoever you wanted to. There wasn’t this constant reminder of the color of your skin.”

Signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers but drafted away by the Pittsburgh Pirates, Clemente attended his first Spring Training in Ft. Myers, Florida in 1955. As a twenty-year-old ballplayer, he encountered the open racism that existed in the south. He and three other teammates were not allowed to stay in the same hotel as white players and often had to eat their meals on the team bus while the white ballplayers dined inside of restaurants.

In a portion of an interview from later in Clemente’s career, he speaks about the indignity of sitting on the bus and having white players offer to bring back sandwiches for him and other players. He knew that things would have been different in his homeland. “We are in Florida,” he says, “not too far from Puerto Rico.”

In a portion of an interview from later in Clemente’s career, he speaks about the indignity of sitting on the bus and having white players offer to bring back sandwiches for him and other players. He knew that things would have been different in his homeland. “We are in Florida,” he says, “not too far from Puerto Rico.”

The early years of Clemente’s career in Pittsburgh posed its own challenges. White fans viewed him as a black man, and African Americans saw him as culturally different, or foreign. Sportswriters didn’t help foster an understanding of Clemente or other Latin players by quoting Clemente’s broken English while also Americanizing his name as Bobby Clemente.

Cepeda, a native of Puerto Rico, says that Clemente had two strikes against him, “being black and being Latin.”

Despite a noteworthy performance in 1960 that included a spot on the National League All Star team and a World Series win by the Pirates, Clemente finished eighth in National League Most Valuable Player balloting.

Author George F. Will, another interview subject, says that Clemente might not have been the outright MVP that season, but there were certainly not seven more deserving players.

Clemente’s struggles with racism and cultural misunderstanding are poignantly told through the documentary’s interviews and through Smits’ narration. Dealing with dislocation, Clemente appreciated reminders of family and home. He befriended a teenage fan and her family after the seventeen-year-old spoke to him in Spanish when asking for an autograph. Clemente also spent his off-seasons at home in Puerto Rico where he conducted baseball clinics for underprivileged children and had a goal of building a youth sports city.

Clemente’s status and popularity as a baseball player swelled during the 1960’s as immigration to the U.S. from Latin America and the Caribbean grew. The number of Latin ballplayers in the major leagues also grew during the sixties. In 1971, the Pirates returned to the World Series with a largely African American and Latin roster. Clemente was 37 at the time.

Clemente’s status and popularity as a baseball player swelled during the 1960’s as immigration to the U.S. from Latin America and the Caribbean grew. The number of Latin ballplayers in the major leagues also grew during the sixties. In 1971, the Pirates returned to the World Series with a largely African American and Latin roster. Clemente was 37 at the time.

“We were like a family back then,” says teammate Manny Sanguillen, the team’s catcher and a native of Panama. “We weren’t thinking about color. We just wanted to win.”

As the documentary nears its conclusion, the pinnacle of Clemente’s career is revisited during that 1971 World Series, when the Pirates defeated the Baltimore Orioles in seven games. Having played in a smaller television market in pre-ESPN days, this was Clemente’s chance to perform on the game’s biggest stage once again. Also, for the first time ever, a World Series night game had been scheduled, guaranteeing an even larger television audience. Clemente seized the opportunity, batting .414 with two home runs while earning the World Series Most Valuable Player award.

Clemente would play one more season for the Pirates, collecting his 3,000th hit on the final at bat of his career in September of 1972. Three months later, he boarded the DC-7 bound for Nicaragua.

In footage of his televised locker room interview after the final game of the ’71 World Series, amid the delirium of victorious athletes, he took the time to deliver a message to his parents in Spanish before continuing the interview in English. The gesture was especially meaningful to Latino baseball fans. His home, his family, other people, were always in his thoughts.

As Clemente’s friend Osvaldo Gil says during this fine documentary: “On the greatest day of his life, what is his first thought? Family and country.”