Age As Disease: Nick Haymes’s Gabe

07.08.12

- Gabe

- Nick Haymes

- Damiani

- 128 p.

- $40

There’s a video on YouTube of Gabe Nevins holding a sign that reads: “WILL RAP AGAINST YOUR MOTHER FOR MONEY (OR WEED).” Gabe looks tired, wired, and slightly ruined. He goes on to do exactly what it says on his sign, with a couple of guys off camera laughing and egging him on.

The Gabe on YouTube and many of the Gabes that feature in Nick Haymes’s new book of photography feel like a very different Gabe Nevins from the one that I first saw on posters for Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park around 5 years ago.

In 2007 I was visiting Paris, drinking way too much, and feeling at a particularly low ebb. Nevins’s face was a constant on walls and the odd magazine cover in a blurred city that I was melodramatically using as a temporary emotional escape plan. Spurred on by the advertisements, and being fond of some of Van Sant’s previous work, I went to a cinema on the Champs Elysees with a friend and sat down in a Version Original screening of the film. I remember thinking it was cool it was that there was a group of old women at the screening, seeming to nod appreciatively at the screen, in a way that I hadn’t seen pensioners do in England. I remember getting goose bumps and teary when Elliot Smith songs started to play. I remember being impressed with how great Nevins was, and how the mood of the film seemed to fit with certain themes and interests that I was trying to point my own work towards at that time. I watched the film at the right time, basically. My friend hated it––aside from saying that he thought Nevins was quite cute.

Nevins was a non-actor chosen to be a lead actor after catching Van Sant’s eye at a casting call for extras. It doesn’t take a long stretch of imagination to work out why. Gabe Nevins has charisma; Van Sant cast him perfectly. Paranoid Park wouldn’t have been as great without him. He has an untraceable but unmissable charm that must have snagged Nick Haymes, whose new book Gabe attempts to catch whatever it is and all that accompanies and/or fuels it.

My initial response upon reading about Gabe was an uneasy joining of fascination and suspicion. If I were to try and identify the reaction precisely, I guess it would all hinge on the issue of exploitation, which if the early reviews of the book are indicative, is a subject that will no doubt continue to trail this particular work.

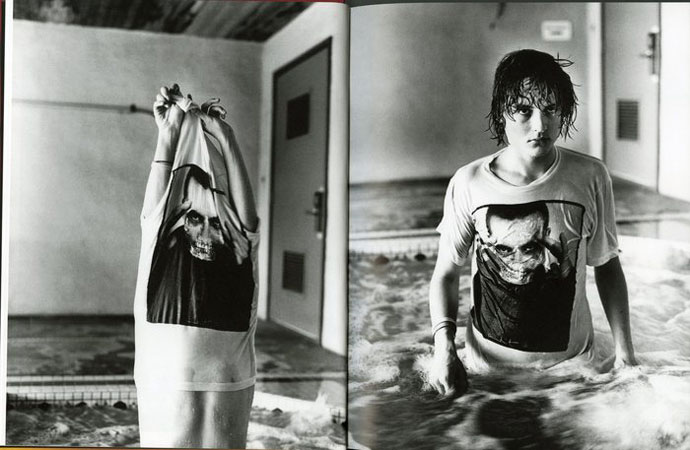

The photographs that Haymes displays in Gabe––of Gabe––almost posit age as a disease, from the start of the book where Gabe is snapped on promotional duties for Paranoid Park, to the later shots in which he’s naked and older, his body covered with red blotches, his facial expressions hard to read, sometimes close to tears. Which isn’t to say that at the start of the book Nevins’s gaze isn’t intense. Throughout the book it often looks like his eyes are drifting off into something else, far away from what the camera can actually see. But the later photographs offer up a young soul who looks physically ill, maybe trapped.

There’s no getting away from the fact that the preponderance of Gabe is a document of disintegration. There are photos of Gabe having fun, laughing, maybe high, pissing, some where it looks like he’s ready to fuck. Then there are pictures of the same person looking lost, fucked up, in pain.

I’m still trying to work out what I actually feel about the book. Lots of things. It’s uncomfortable, but it’s also compelling, and whatever suspicions I had of Gabe––even if I did think that something was wrong with the book––whatever that was didn’t stop me from ordering a copy as soon as I’d read about it and paying money to see it up close. The more I think about it the more I come to think that perhaps the suspicions that I held about the book are closer to me personally than I’d like to admit.

It’s intensely intimate, which hints to the trust and the kinship between the photographer and the subject, which has been mentioned in the interviews that I’ve read with Haymes concerning this project. The emails from Nevins to Haymes also suggest a loyalty, a bond. I started to think about Nevins’s role––he was obviously complicit in the photographs being taken, obviously approved of Nick Haymes wanting to document his life. He was aware of the allure that darkness and sadness can have––self-aware enough to email Harmony Korine, and offer himself for a part in the director’s films, famed for their masterful journeys into the surreal side of fucked-upness. “i would do ANYTHING under your direction” Nevins writes in one email featured in the book “…serously [sic] lets make a piece about a small townwith [sic] a bunch of inbreeding??”

I started to wonder if I was just trying to make excuses for myself. It became clear that I wanted to believe that everything in this book was okay and that it was okay to buy and that it was okay to look at. I realised that I wanted to make it clear to myself that Haymes was sincere, probably because I knew that if he was, then so was my interest in the book. It’s strange because I’ve very rarely wondered about whether or not I should like a piece of art, it’s usually just been instinctive, I’m drawn to something or I’m not, I connect with something emotionally or I don’t. Occasionally there have been times when I’ve been drawn into debates with myself about why particular things have appealed to me––for example, I’ve spent time analysing what it is about Peter Sotos novels that draw me in so feverishly. But for whatever reason, Gabe seems to ask me questions about accountability, about my role as the viewer, the audience, the consumer who wants to see someone else’s sadness at a distance, whatever the fuck it makes me.

I do know that on an emotional level I find the images in the book engaging, obsessive, beautiful, sad. Often all at once. With the other stuff … I’m still trying to work it out.