A Story About the Body: A Review of Rachel Levy’s A Book So Red

21.01.16

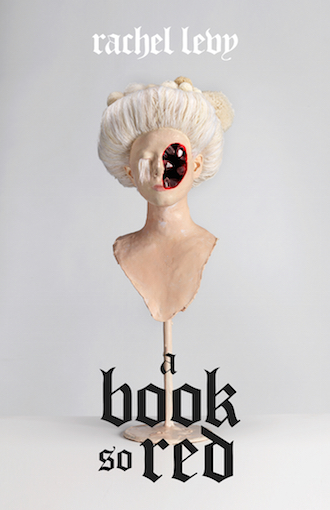

A Book So Red

A Book So Red

by Rachel Levy

Caketrain

$9 / 140 pp.

The best metafiction tells story as competently as it supplies the usual imperatives to reconsider the act of reading fiction (by which I mean, what that act is good for, if anything) and the ideological ramifications (political, aesthetic, and so on) of certain modes of literary representation. Rather than confine herself to mixing a new bag of old tricks or verbalizing a schematic diagram of how the old tricks work, the author devises a middle way, combining traditional storytelling elements with fresh self-awareness, reaching for a new genre of storytelling or rhetoric when the one in use loses its edge. In other words, the best metafiction says no to nothing but instead remains open to everything.

Some recent examples I know include Susan Steinberg’s Spectacle, Amber Sparks’s May We Shed These Human Bodies, Gabriel Blackwell’s The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men, Joanna Ruocco’s Another Governess/Least Blacksmith: A Diptych, Blake Butler’s There is No Year, and Tim Horvath’s Understories. I am not attempting to form a “best of” list (my reading is nowhere near up-to-date) or to be exclusive but to give a sense of the kind of fiction I mean, fiction where story mixes freely with narratorial self-study.

Rachel Levy’s very short, sad, and funny novel A Book So Red (Caketrain 2015, Paper) is another example. As a novel, the object looks and feels light, presenting about a hundred pages and perhaps ten thousand words. Further challenging formal expectations is the book’s narrative organization into seventy-eight brief chapters, some as short as half a page. The writing, frequently dialogic, is parceled into discrete episodes that occur chronologically, though these episodes are themselves grouped into (roughly) four larger sections, which are neither titled nor marked off by breaks but signaled by shifts in setting, character, and storytelling. The book’s conflicts and comic set pieces dramatize this same problem of formal expectation. The novel opens with the nameless first person narrator attempting to romance a recently divorced man (named, it turns out fatefully, Horst) who responds by articulating his disappointment and irritation with the narrator’s supposed inadequacy as a woman. While Levy plays this arrangement for laughs (Horst’s first words, about his recent divorce settlement, reveal a bloodless and unimaginative vision of life: “I have taken her ostrich”), she makes it clear that the imbalance in their partnership favors Horst (a bar late in novel, perhaps representative of the wider world, “bustle[s] with Horst-like men”). Horst may prove a selfish and cold-hearted lover with an emotional dependency on a nasty little lapdog, but it is the narrator who endures loneliness, unsatisfying sex, frequent insults and snubs, a lost foot (this is, among other things, a portrait of a fallen woman), and finally banishment.

Subsequent sections take place on a farm where the narrator’s father maintains a chilly distance from his daughter; a country estate where the point of view and storytelling shift to somewhat destabilizing third person fable of chambermaid violently taking her lady’s place (is the narrator this chambermaid? is she an imposter on this count, too?) and where Horst lies ailing after an accident; and finally Berlin, where the narrator feels old and unwanted (“Soon I would die and leave no sexual partners to mourn the loss of me”) and finds short-lived hope in a relationship with a woman named Mitzi. Having embarked on this journey toward the next disappointment, the narrator describes what will be a doomed attempt at eating a holiday cookie:

In the beginning I tried to eat a human-shaped cookie left out on a plate. There were three circles of icing between the face and the groin. I started at the bottom so I could eat the head last. That way it could experience everything. (109)

This comical and unsettling image pulls together much of the foregoing material. It suggests the pain of loss (seriocomically, for the cookie) and the pleasure of sweet spots (for its eater), which reflects the narrator’s arrangement with Horst. But the metaphor is more complex than that, as anyone with a body and sharp eyes has by now noticed: the erotic language of second sentence suggests the three most prominent erogenous zones on the female body between groin and head, which, when “eaten,” deliver pleasure to the female body as well as giving excitement to the owner of the operative mouth. Also contradicting any supposition that the eater will claim all the pleasure are the prepositional phrase and subsequent noun-predicate combination that open the paragraph: one senses eating will be work for the narrator. The act of eating, in any sense of the word, requires effort. Any act of eating will require an encounter of resistance. The act of eating cannot exist without the state, for something, of being eaten.

Perhaps, then, it would prove useful to consider eating-and-being-eaten as a single phenomenon: one cannot exist without the other. The same might go for taking-and-being-taken-from, as well as for writing-and-being-read. In all of the above, a two-way exchange of pain and pleasure maintains. Further, the processes above have the effect of disorganizing states or quantities. One moves food; another possessions; the other meaning. The baker cannot put back the flour and sugar the customer has chewed up and digested; the robbed cannot generally reclaim what has been taken; nor can a writer or storyteller restore the first arrangement of unread written material after a reader has made new sense out of it. Like anything else in life, writing depends on a transactional counterpart for its existence. In this world, it seems, one must not only eat or be eaten: one must eat while being eaten. One hopes to outlast the others, or to at least enjoy a lion’s share.

The cookie image is charged with this meaning by, among other things, a description from earlier in the novel–one in the chapter sharing the novel’s title–in which the narrator’s father refers to the stomach of a slaughtered bull as “[t]he book… When he slit open the stomach, the folds fell apart like pages.” This description calls the reader’s attention back to novel’s unusual formatting, its composition of many short chapters. The reader becomes aware of the text as the cuts of the butchered (sometimes literally) narrator; the reader sees a novel or story as the butchering of life-experience, the cruel necessity of the trimming away of certain parts; perhaps the novel (this is a book so read, after all, using such literary materials as fairy tale images, proverbs, the fallen woman figure, and the marriage plot) has been in need of a good butchering. Beyond the formal issue, there is the matter of interpreting or making sense of any free-standing being or thing as an act of butchering. We cut people to bits to make stories of them; we do the same thing to ourselves, choosing what to tell and what to omit. This book, whether imagined as a series of cuts or bites, presents a character, itself an artificial band of consciousness, as more accurately imagined as a frequently broken and crooked line as opposed to a continuous straight one. Turns out the self is a kind of fiction, too.

***

A Book So Red asks to be read as much a platter of the most select cuts as it does an account of a woman’s undoing by (sometimes sexual) takers (though, yes, uptight male reader, she is a taker, too, just like everyone). A consequence of this formal execution is the invitation to read the book as one wishes to, just as one might be invited to act as one wishes on another’s body in certain kinds of romantic relationships–especially those in which women might be considered a kind of chattel (however consciously or publicly). Making the text a dare to be bad reader is, I think, a gambit that succeeds for Levy in the end. The reader reading this book takes measure of its narrator’s suffering, and in taking measure, looks for what she has overlooked: all the losses this story leaves out, all the slings and arrows a ravaged storyteller–who might be anyone–never even bothers to remember, never supposing a reader–or a listener–might ever care to know. This novel is not merely a book about fiction but a challenge to listen, to look, and to read more closely.