A Review of Sade Murphy’s Dream Machine

08.01.15

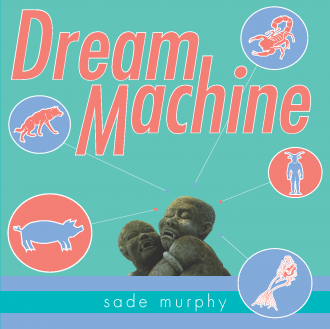

Dream Machine

Dream Machine

Sade Murphy

co-im-press

75 pp. / $15.00

Louise Glück writes in her Wild Iris, “At the end of my suffering, there was a door.” Conversely, Sade Murphy’s Dream Machine asks, “At the end of her dream machine, is there a door?” And what will that door open into?

Sade Murphy is from Houston. Like Rothko, she is an artist. Some artists work in media such as digital installation, painting, printmaking, and sometimes collage. What kind of literary medium is Murphy’s Dream Machine? Is it a hybrid between postmodernity and arithmetic? Between textual hallucination and dreamscape? Between prophecy and semiautomatic coital positions? Does it bear resemblance to Keith Waldrop’s dada-lyrical and radiant visual collages? What kind of poetry crop do we want and expect from a poet born in a city filled with magnolias?

In an interview, Murphy shares with the world that Dream Machine birthed from a writing exercise where she recorded the previous night’s dreams over breakfast. She has named her poems with numbers derived from various, selected places such as Imaginary Numbers, Biblical Numbers, Prime Numbers, Fibonacci Numbers, etc. She even has a category for Sexy Numbers. She connotes the number “0” as a sexy number. When it first appears to you, you realize that it makes sense why zero would be such. The round “O” for Orgasm. Surely it can’t be anything else.

Sade Murphy begins with this line from ‘Post Prelude to Dream Machine’: “The orgasm backfired muffled sobs on its crest.” As a reader or a lover of intimacy, you don’t expect an orgasm to backfire, but it has, and it appears on your first neonatal sampling of her work. So you continue as you suck on your thumb, hoping that by the end of the poem, the orgasm isn’t holding a handgun and pointing at you. You discover that it isn’t. In fact, most of Murphy’s lines are esoteric in themselves, rarely repeating though they multiply in their inventiveness. In fact, the only frequent visitor that traffics Murphy’s world goes under the name of “Him.” When “Him” is capitalized like so, you can only refer to Jesus and Houston because that is the only place where Jesus would want to be, you assume. As you travel down the highway of the dream constructions of Murphy’s world, you discover that you wish you could live in Murphy’s dreams for three primary reasons:

1) she has more interesting dreams than you do (“Damn unicorn gorging on cucumbers and tiger lilies”;

2) she has a better subconscious than you do (“Try for a caustic coup and do callous hiccups”;

3) she has a better memory than you do (“A catharsis of feathers, camouflaged lavalieres, percolating rococo kids in full French & Indian War regalia.”)

Try recalling that upon waking up and most importantly, try limning that in one line!

The most interesting aspect of Murphy’s work is her translation. How does she translate the visual world into the textual? She does this by giving herself the sovereignty and boldness to explore her interior worlds and to avoid the conventional methods that hold back her creative, intellectual properties. She is like the Charon of the dream world, where if you offer her a coin by reading her work, she will take you across the visual Acheron rivers of her dreams to the proper chthonic palace of her words. After all, as a kinetic, visual thinker, I can’t seem to be able to imagine (in reverse) what the visual world of “Humidity will flirt with your mouth” or “bedazzled vaginas glitter gaudy” or “equestrian socks” or “mausoleum screams” etc. would look like, but she has that fearless ability. She also invites her love for numbers to come with her as well. As you will notice, when numbers and letters co-exist, they heighten their sexual altitude even more. Manuscripts that capitalize on this level of sexiness often live an exotic, unquiet life, as demonstrated by Murphy’s book. Her sexiness lives here from poem titled “33”:

33 Humming to black and white British people. Projected optic maroon angels pinching your sideburned sunburned love handle. Do the French inhale for me and peel the camel hair shirt from the exquisite corpse of charity. Impressionistic and impressed, I am under every street light, shooting cannonballs of fleeting fireflies, carouseling at three thirty. Envy is an umbrella against a sandstorm of affection. You rest somewhere between queue and ewe, savagely pretentious, retrieving letters from the recycled rubble.

More than her ability to translate, Murphy’s talent exists in her ability to create magic. She gives language a new periodic table of elements. When she combines and recombines the different chemical elements of her linguistic playfulness, we expect combustion. Her dream recordings are a series of combustion, igniting the poetic landscape of the Digital Age. So what do readers expect of this Houston-born poet who loves the dictionary, who loves word play, who toils with the linguistic hallucinogens called dreams? Do we expect her poems to smell like magnolias, like an art gallery, like The Niels Esperson Building, like an Art Car Parade, like George Bush Intercontinental Airport? I don’t know, but what I can say is that her dynamic, polychromatic poems do not intend to lie still like a dead leaf, waiting to be decomposed by time and neglect. Her poems are born into the world to become Pythagorean medusas meant to make love to a lexical Hydra.