A Review of Kate Durbin’s E! Entertainment

04.09.14

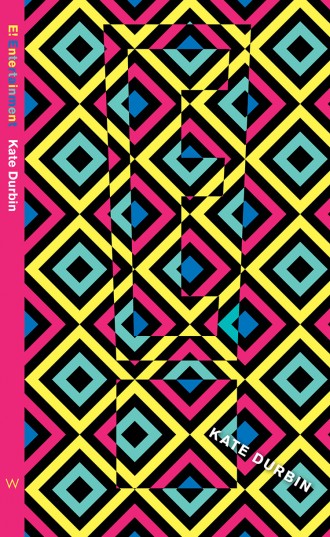

E! Entertainment

Kate Durbin

Wonder

205 pp. / $15

As I binge read the entirety of Kate Durbin’s book: E!, which transcribes reality television clips into an experimental literary remix, I emerged with new clarity on these stories and my own role as viewer, most notably in Durbin’s text when Kim Kardashian confesses to Stepdad: “It’s like I’m forgetting what this is all supposed to be about.”

I am reminded of how cults work.

Former cult member Lisa Kerr explains, “Brainwashing works in a layering process. First, the victim is isolated; second, limits are placed on what they see, hear and do; and finally, the person doing the brainwashing raises uncertainty about the victim’s old beliefs and habits.” Kerr then cites Kathleen Taylor, highlighting cults ability to “refashion identities” adding, “Brainwashing is not just a set of techniques. It is also a dream, a vision of ultimate control over not only behavior but thought.”

Isolation, “amnesia” and “refashioning identity” seems rampant in what makes reality television work too, and not just for Kim Kardasian, but both of us. I am implicated here as well, alone at home with my screens, focusing instead on subject and signifiers more so than the humanity behind it, often forgetting– Kim Kardashian is a real life, feeling person, or, this is what I’m reminded of as I flip through the pages of Durbin’s book.

Unfortunately, the production of television transforms or “refashions” Kim into a container for where I can stuff my thoughts on class, commercialism, or gender. She is a symbol of upper-class identity, akin to Patty Hearst, a kidnapped media heiress. Did she go willingly into the bank with a gun? How much is the real Kim implicated? Who is the real Kim? What was she wearing? Does she want to wear that or is she forced?

This translation of “Kim the woman” into “Kim the thing” generates a certain sense of isolation and tunnel-vision. Perhaps Kim’s constant attraction to self-promotion, designer heels, or over-indulgent product placement is a simple side-effect of Stockholm Syndrome: identifying not only with her production captors, but also identifying as this thing to be captured and produced– or to reiterate what Kim says: “It’s like I’m forgetting what this is all supposed to be about.”

Identity and branding on television complicates the relationship of not just seeing oneself, but also being seen by others, and this relates not just to Kim, but the whole reality show spectrum. For instance, Durbin includes a transcript of The Real Housewives communing at a dinner party with cocktails, declaring themselves “alpha-females” or as Wife Lisa jokingly adds “bitches.” This brief moment of play quickly devolves as another guest, named Medium, labels Wife Kyle as “talking more easily to males. ”This on-screen accusation results in division. Wife Kyle rejects this identity while Wife Camille claims it for herself, stating, “That’s me,” and “I am definitely more comfortable around men,” but Medium does not relent with her own ephemeral casting. In the Housewivesfranchise, Medium is an actual psychic-like person, but in Durbin’s text Medium could also be “the message” intrinsically echoing Marshall McLuhan: “We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.” As we read on, more chaos ensues, leaving us in a state of confusion as well, trying to recast according, guessing constantly who is the most trustworthy, the most fun, the most psychotic, the most sane–but there is never any logical resolution, only a strange pink canopy glow of pretend that pulls us in deeper into the world of simulated reality, echoing Barbie variations, role-playing, and clique backstabbing: experiences from childhood that’s over, but I don’t know, maybe not? My attraction to reading and/or watching these exchanges feels like a nostalgic reversion, and in some strange way, I wonder, if I am captured by these women in the same way that production companies capture them: my own Stockholm Syndrome.

Thankfully, throughout E! Entertainment, Durbin, to her credit, doesn’t push an agenda with how we should feel about watching Wives or Kardashians or reality television in general–it’s not good nor bad. Instead, her text reveals a deep meditation on what we see from designer heels to cocktails through image juxtaposition and repetition. Much attention is given to the simple recordings remixed: excerpts that function on a archeological/sociological level. The questioning comes from inside the reader after reviewing the evidence. For instance, in Durbin’s text, when Anna Nicole Smith says, “Talk to me. For the baby? How do you know it’s not a real baby? How do you know it’s not a real baby?” I am confronted with Smith’s infamous “clown video” footage as a literary dub step, structurally presented by Durbin as a play without stage directions, only samplings of direct dialogue reorganized into separate monologues back-to-back, creating another absence, lostness, or isolated reality. The video alone is disturbingly sad, but Durbin’s remastered transcript speaks to a larger conceptual conundrum–one of secluded production or the zeitgeist behind the curtain. Durbin cites CNN as a preface to the section for clarification: “Prosecutors presented this video as evidence that Howard K. Stern conspired to keep Anna Nicole Smith in a drug stupor. Stern’s lawyers say Smith was acting for the cameras.”

Here, I’m reminded of Andy Warhol– his statement: “Now and then, someone would accuse me of being evil–of letting people destroy themselves while I watched, just so I could film them and tape-record them. But I didn’t think of myself as evil–just realistic.”

In the cult of entertainment, where does the acting stop and the drug stupor start? Which one is more realistic? I struggle to define reality merely as a riptide of shredded physical and emotional violence through a lens: throwing a glass, flipping a table, or tightening a choke hold–especially when, upon closer scrutiny, the reasoning behind a televised fight reflects more of how someone is seen than seeing one another. To wit, if you watch The Real Housewives long enough, the brawls most often are not even in response to different political views or ethical values, instead, they’re a reaction to slander through tabloids, interviews, or social media–this idea of someone tarnishing their brands, their egos, themselves in public.

On this note, the most compelling aspect of Durbin’s collection is “The Girls Next Door” section, where interiors are described, minus the women. Here, Durbin writes beautifully: “In the pool filters are tangled balls of hair in stages of blonde,” and “The sponges in the shower were once natural, living creatures.” Durbin’s female identities in this section are never proclaimed. Instead, their sexuality costumes are left behind, collected in shrouds of scenery, part of a still life. Comparably, what once was Marilyn Monroe was previously Norma Jean and now is only a dress in a museum.

Maybe this is why I keep watching–for the awakening or that hopeful moment when each televised woman escapes the cult. I just keep forgetting that I’m a part of it as well. I honestly do love a good cult story. I think, in a way, we all do. This idea of how adaptable we are to alternative realities or could be, and this slipping is terrifying but also curious. How could this happen to people? How could she do that? It won’t happen to me. It already has. It’s a horrible type of alchemy: turning people into things. This is what Kate Durbin’s clever reconstructions bring up for me: how do reality star behaviors mirror our own online? How do we objectify ourselves digitally and is there a way for us to escape the faction as well?

These are questions I’m still asking after closing Durbin’s book, which most certainly is the sign of a solid read.

——————–

E! Entertainment by Kate Durbin is now available from Wonder.

Stacy Elaine Dacheux is an artist and writer whose work has most recently been shown at studio 1.1 in London and featured in The Los Angeles Times.