Bizarre Generosity: A Review of Diane Seuss’s Four-Legged Girl

11.02.16

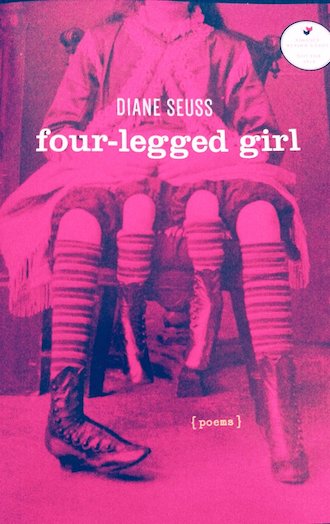

Four-Legged Girl

Four-Legged Girl

by Diane Seuss

Graywolf

88 pp. / $16

Myrtle Corbin, a major inspiration for Diane Seuss’s Four-Legged Girl, joined the circus at thirteen because she was born, in 1868, “with four legs—a full-sized pair and two smaller ones that dangled rather uselessly between the standard appendages. The miniature feet had three toes each. There was a club foot on one of the standard legs. She also had two pelvises, two vaginas, and two menstrual cycles. She gave birth to five children—two from one side, three from the other.”

Seuss writes: “I love and lust after Myrtle Corbin because she is queered and empowered by her idiosyncrasy . . . I experience my own body as a spectacle, an exhibit, a performance, and a condition.”

When I met Diane, nobody would shut up. I deplore nepotistic reviews, so I’ll say right off the bat that we crossed paths at a residency. That month in the woods was the most generous opportunity and most intense social crucible I’ve ever flung myself into—and I’ve done a lot of strange things.

At MacDowell, the most varied and talented group of artists I’ve known fired bon mots at each other: a twice-daily tennis match in a paradise bolstered by hidden labor. [i]

Of course, many of my fellow Colonists are now lifelong allies; our bonds were genuine and meaningful, and it was the work that took place between breakfast and dinner that was important. But as an introvert and weirdo, the golden tennis court became exhausting. By the time Diane showed up, what little fucks I had left to give were abandoned at my studio door. Vocabulary—much less banter—had given way to a marked inability to sustain the same three questions.

This is how I immediately knew Diane was rad: she didn’t try to compete, didn’t try to ask the requisite questions, and told exactly zero dewy-eyed n00b stories about being able to see a squirrel from her porch. (Internal monologue: Yes, we’re in nature. Yes, chickens. I’ve been in nature for several weeks. It’s lost the shine, even if I have developed a close relationship with my driveway-spiders and that bird that sounds like death. Just you wait.)

Diane befriended another poet—one of two people of color out of 31 colonists—and they’d get to dinner a bit early and sit at a table that stayed half-empty, talking in low murmurs about, from what I heard, race and class and their lives and their children. Those of us who’d bonded during the height of summer flitted around chattering in cliques. The population shrunk rapidly. The air felt changed: summer’s dregs going fetid, ghostly. They wouldn’t linger. They didn’t seem unfriendly so much as uninterested in playing the game. They took their breakfasts on the porch, not talking much. They watched the dew burn off the meadow, or perhaps something I wasn’t paying enough attention to see.

And yet—I’m going somewhere with this—although I never made an effort to get to know her because my brain was broken, I ran across a poem somewhere months later and promptly devoured everything I could find. She is astounding. I’m not writing this because I barely know her. I’m writing this because everyone should. Her work is phenomenal: mesmerizing, generous, kinetic, and frightening.

While I was avoiding writing this by bitching on Facebook about submission fees I’d paid while procrastinating, Diane messaged me with a suggestion about a grant, put me in contact with someone, and offered to give me a small sum herself. (I refused, of course.)

That, dear reader, is literary citizenship in a nutshell.

I’m reminded, here, of another poet I know who, a few weeks ago outside a reading, gave a homeless man change and then, when he kicked his paper-bagged beer over, knelt to set it upright. I’ve heard emerging poets question her bizarre generosity. I’m pretty sure it’s genuine, even absent of hope for reciprocation. We find this inexplicable. I find that sad.

There should be more room for generosity, and Seuss has hewn it. Via Myrtle’s circus leitmotif, coupled with nods to Dickinson’s more privileged kind of freakdom, the poems in Four-legged Girl tackle embodiment and womanhood—in the sense of both femininity and gendered oppression—via a swathe that charts several decades of relationships with men: any muse’s hidden labor for junkie boyfriends, poet-bros she’s known, and a working-class hometown. Seuss writes of Burroughs, Jackie Curtis, and a boyfriend:

“I stood on the sidelines wearing a vintage

muskrat coat—those were fur-wearing days. You’re delicious, Jackie said to me.

I think she thought I was in drag too, my eyeliner curling into my temple,

my hair like a spillage of blue ink, and I was, playing girlfriend, playing

secretary, sexpot, writer. Beneath it all I was a farm girl watching locusts devour

the crops, wondering what all the fuss was about . . . There is

no redemption in having outlived them all, but having outlived Burroughs, that

makes me smile a bit on the inside, though you’d never know it to look at me.”

Seuss employs surprising, wry turns of phrase embedded in poems that are decidedly lyric–dense & richly metaphorical, wine-dark: “Waning / moonlight on hospital sheets on the line, and the christening gown // brushed with pollen, cut into costumes for canaries.”

Seuss’s work is suffused with compact details that owe much to lyric poetry but are free of fealty to the academy. Beloved symbols of old white guys abound—animals, nature, et al—but her wisdom is self-taught: folk tools such as Brer Rabbit come to mind. Seuss’s speaker is more Helen herself than the story told about her. Her strangeness and touches of magical realism are world-building at their best, as the myths are non-hierarchical: “a shot glass half-filled with music” or “more eyes than a potato bug has legs.”

Seuss’s chimerical mysticism invokes the ghosts of those already in the underworld: “I’m sure / there are other kinds of ghosts other places, // sad angels wearing bloomers and fanning their wings, / but here their faces are made of gristle and their eyes / are red from too much Thunderbird. They want to steal / our valuables.”

Too, she’s expertly rendered Good-Ol’-Hellscape New York, blinkered by AIDS and crack: “I blew soot from my nose, / and the homeless, not yet rounded up, frozen blue on park benches / . . . I was not yet muffled by useless wisdom and silly ambitions / which are stand-ins for exhilaration and what is called love, sweet / until it was bitter, and when it was bitter I spat it out / onto the street, which glittered, in winter, with road salt, / fish scales, sequins and loose change.”

The pacing of the text’s five sections comprise an almost-linear chronology of becoming non-linear: coming into oneself as unsafe. The wisdom Seuss gained through time isn’t an easy recovery: no capitulation, no smoothing into normality. Hers is a refusal, an arrival at lack, at largeness: a comfort in one’s disruption, in being disruptive:

“An unbeautiful woman is her own

antidote. Her own black granite basilica. Go ahead. Walk in, though you must

enter her unshaved vulva, oh the vines, the vines, the brambles that break

all axe heads and mastheads! If she is ashamed, she is an implosion of sacred

spaces. If unashamed, she’s a foul explosion of barbells and stars, crucifixes

crosshatching the air black.”

Here, Seuss addresses the loss of possessing “beauty” (as specifically tied to youth) as a performance against authority. Her loss isn’t that of a former-downtown-cool- middle-aged poet who moved to the suburbs and had a kid while bitching about Pilates. Her work addresses the unexpected gift when refusal is chosen, when safety was not chosen, when one has decided not to perform or participate: age grants invisibility, e.g the permission to not perform because one’s beacon for misogyny to target has faded to a warm glow.

“Some of us claw our way to the bottom, transcend downward/ There at the hub/ of the drain, we swirl.”

In several poems, Seuss addresses women’s work, particularly the tokenization and misogyny inherent in both poetry and working class labor. In “Hub,” for example, a long poem about umbrellas, the speaker’s father “would walk in the rain like his tumors were made // of sugar” until, after he died, her mother “disappeared” his clothes and “rescinded anything shelter-shaped, including the parasol flowers.” Then, as a young woman, a paper umbrella is carried “only // to cut a romantic figure, a small-breasted lusted-after / girl flouncing off / to the secretarial pool . . . Translucency / served my purposes, which were as transparent/ as glass shoes.”

This umbrella invokes the history of repression embedded in a lifetime’s twirling succession of everyday objects that are themselves imbued with cultural mores around safety and performed femininity. Seuss explains: “from the hub arose many begettings . . . Culture begat the faux peony, the petals sometimes made of silk, the stem, a hub of cold wire wrapped in green tape, which begat capitalism, which in turn begat tilt-o-whirls, tennis skirts and fireworks, all things that spin and flare for no reason other than that spinning and flaring greases the machine, which begat the idea for a solar system—bodies circling the hubs of other bodies—which begat weather, and Christmas, which begat shopping, and denial—thus, our decision to believe that the ants crawling over the unbloomed heads of peonies were somehow rehabilitative.”

I think I’ll keep coming back to Seuss for her descriptive power, particularly as a tool for disruption: she is parsing the irreparable, rather than neat bow-tying or hand-holding. Through it, she manages to both evoke the past and to be annoyed at nostalgia; to describe trauma without the description being a stand-in for “healing.”

If Four-Legged Girl has a shortcoming, it’s a reliance on blowsy description our generation has ceased to fashion in favor of detatched, laconic irony. Yet Seuss is funny. Her humor is no less self-skewering or wry: it’s sincere, subtle, and deeply uninterested in being a cool kid. “Still pretending to be girls, and hetero, wearing lacy knickers and shit kickers. / We were, relatively speaking, housewives. / Haute cusine was Bisquick pizza and lychee martinis…. Remember, somebody kidnapped you and set you up in a whorehouse / in West Virginia. So not cool. / I had to thumb a dangerous ride to break you out.” Four-Legged Girl is a life study in that it’s a book about really having lived. Seuss’s stories would probably frighten children, but she trusts her readers are adults.

For an example of how to use both rich description and genuine humor, buy this book.

————————–

[i] Next time you’re annoyed or saddened over something in your life, pulling out to assess your problem meme-style is a super-fun exercise in mapping the intersections of privilege and suffering in your current lived experience—a quick flash of politicizing the personal. If your problem it is My picnic basket fell off my bike or A cloud came over the sun while I was trying to sunbathe in the amphitheater, you might not have much police brutality to worry about.