A BYRONIC MOTHERFUCKER: An Interview with Adam Gnade

27.06.16

I first came across Adam Gnade’s work over a decade ago. I had just moved into my first apartment, in a ‘cool’ neighborhood in San Diego, after having grown up in a decidedly ‘uncool’ suburb twenty minutes north. Gnade was an editor at Farenheit, a free newspaper that I picked up from the coffee shop across the street every Tuesday immediately after it was published. The paper was basically what all free weeklies strive to be, a portal to the best local shows and bands that an uncool suburb kid like me might never have known about otherwise. Like most truly great things, it didn’t last long, dissolving just over a year after it was founded.

Gnade came across my work about a year ago, liked it, and then messaged me about it. We have a fair amount in common—we’re both writers who are more than slightly obsessed with the side to San Diego that has nothing to do with beaches or fish tacos, and have since left our sunny hometown for a more rural life. Gnade is the author of over a dozen works, most notably Caveworld, a novel that tells the story of a city– San Diego–and a family–his own–over the course of several decades, and The Do-It-Yourself Guide to Fighting the Big Motherfuckin’ Sad, which is fairly self-explanatory, and an indie-press bestseller three years running. Most recently, he is the author of Locust House, a novella that covers a single night in 2002, at a party house named after local legend The Locust, a band that, according to Wikipedia, is “known for their unique mix of grindcore speed and aggression, complexity, and new wave weirdness.” We discussed his work, San Diego, farm life, and more over a series of emails.

Fanzine: Locust House is about a lot of things, but at the center of it is the San Diego music scene of the late ’90s-early ’00s. I think it’s safe to say that we both have mixed feelings about our hometown, but I’ve always felt proud of being from a city that fostered so many great bands – all the Three One G bands, Three Mile Pilot, Drive Like Jehu, etc. Are there any shows from that time that were particularly memorable for you?

Adam Gnade: Some of the best shows were actually wakes. A lot of messy, violent house shows with bands that ripped off the Birthday Party and did it so well, which I think is thanks to Antioch Arrow coming up in the generation prior. Any Relics show, which is a band most people won’t know. Black Heart Procession, Album Leaf, Holy Molar. Any Gravity band and any Beautiful Mutants show and any Locust show. Anytime the after-party ended up in Tijuana. Tristeza anywhere, because their early songs sound just like the landscape of Sherman or Logan or Golden Hill—sunny, looping, nodding guitar parts, hills of sound with big empty blue sky above you and you’re driving over those hills in a rusty terrible car but you’re dressed well, and those synth parts and loops cycling as repetitious as the lines of palm trees on the sidewalks. Their songs “Building Peaks,” “Respira,” and “Golden Hill” are fine examples of that.

I think I’ve never fully been able to grasp San Diego (or Southern California, for that matter). People move there and like it because it is sunny and beautiful and nice, and it is all those things, but there’s something very dark underneath it too. This juxtaposition has made it into your work, and my work, and the music of the aforementioned bands, but I’ve still never been able to put my finger on what it is or where it comes from. Some of it has to do with artificiality, but it’s more complicated than that. What the hell do you think it is?

That’s one of the things I immediately got from [your book] Black Cloud—we’re writing about the same place but it’s not the place of most people who live there. It’s Misfits shirts and threesomes and eyeliner rather than Chargers jerseys and bayside barbecues and sunscreen. I’ve been trying to figure that out all along. Why is a rich, clean, safe beach town so dark? Probably because the land was stolen from Mexico or maybe it’s a vampire town like in Lost Boys. Maybe it’s all the heroin and meth. Or because it’s a very expensive city and a lot of people can’t afford to live there and end up in these trashy, desperate situations. Bands like Prayers are doing well at the moment but San Diego’s punk scene was always very gothy. All of my friends were goth even if they didn’t know they were goth. It’s like the song goes: “The sunshine bores the daylights out of me.” I knew some Byronic motherfuckers in that town.

A few months ago, you were telling me on chat that you’d recently visited Golden Hill–the neighborhood that so many of those bands once called home–and it had grown foreign to you. It used to be kind of run-down, and populated mostly by Latino families, but is now full of condos and hair salons. This kind of spit-shining has happened all over the county, and isn’t unique to San Diego. I feel like it’s happening in big cities everywhere—Brooklyn and San Francisco and Portland and Austin and Chicago. Is this one of the things that drove you to living on a farm in Kansas? How’d you end up there?

It’s a big reason but mostly I wanted to live closer to the land and be left alone to write. It’s very hard some of the time to live rurally, as I’m sure you know, and almost always lonely, but I think it’s good for me. The big wild thunderstorms like we had last night, the quiet days, the rolling green hills, the chickens pecking in the grass … I love all of that from a very deep and fundamental piece of my heart.

Can you tell me more about farm life? What do you guys grow? Are you anywhere close to self-sufficient? What does a normal day look like for you? What are some of the things that living on a farm has taught you?

I love the idea of being self-sufficient but we’re far from it. At this point we’re still city kids fumbling around trying to make things work. But that’s important too. With rural life, maybe as with anything, fumbling’s how you learn. You screw up and maybe sometimes you get it right and then you learn from that too. I guess the thing I’ve learned most is how to improvise. How to take the little you have and succeed as best you can. You have to improvise and be flexible and thrive with the changing terrain, and by that I mean the terrain of your life, not physical terrain. But sometimes that too.

Normal days? They start around 8am. First farm chores. Bring the dogs out into the lower field. Feed them. Feed the barn cats. Let the male goats and the sheep into the far field to graze. Put the ducks and the banty chickens out. Then open the shack where Edith, our female goat, lives with the full-sized chickens. They all go out to graze. I fill up a half-dozen water buckets for everyone, then it’s back inside.

After that I work on my new book, which will take up a good part of the day. Sometimes we go out to the lake to swim (or watch the water snakes swim, which means we stay out of the water that day). Farm chores happen in reverse at dusk. Lately there’s a lot of thunderstorms and there’s nothing better than watching them roll in. Which is what I’m doing right now.

I want to see some pictures of the cute animals and the pretty farm, please?

I think The Do-It-Yourself Guide to Fighting the Big Motherfuckin’ Sad is really kind of an ingenious idea—a self-help book for people who otherwise wouldn’t read self-help books. (And considering it’s been the #1 small press bestseller at Powell’s for three years running, a lot of other people feel the same way.) Reading it made me wish I had come across it sooner, because a lot of the tips are things that I had to learn through a lot of pain and a lot of time and a lot of hard work. What motivated you to write it? Were you surprised at its popularity?

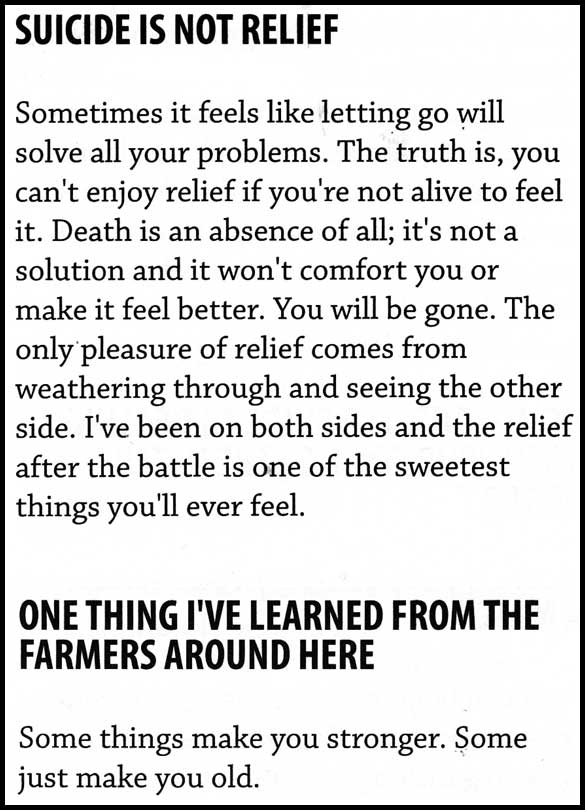

I started writing that one because I was going through some awful, stupid stuff and I needed to take inventory of my life. I did that mostly with lists … well, lists and short notes-to-self. Had no idea it would take off. I feel lucky that it’s resonated with people to that degree. Fiction is what I want to do but I think stuff like Big Sad might be more important. The “good deed” (in the Boy Scout sense) of my life or something to that effect. Still weird to me that my notes to keep myself from blowing my brains out have become this huge thing with so many printings.

Locust House plays around with point of view a lot, inhabiting the minds of four different young people: a group of three friends (all told in first person), and then Agnes, who is grieving the recent death of the closest thing she knows to a parent (told in third). What was the process of figuring out you had to tell this story this way?

I wanted there to be a lot of people in my story because at the very base level it’s a book about a wild, fun party, and lonely parties are something else (though most parties are lonely in their own way, which is another topic altogether). The first version I mapped out was going to have the characters Joey Carr, Ted Boone, the street corn seller whose name I forget, the pregnant woman in the laundromat (who was never named but is an ex-girlfriend of Joey Carr that shows up in my book Caveworld), Marcos the Halloween store employee, Agnes’ boyfriend Steven Boone and her cousins, the priest at the funeral, the drug dealer who’s only mentioned in the second act but shows up in Caveworld… some fictionalized band members would have first person sections too, and then there would be a fourth act before the epilogue that was one sentence from 316 different people at the party told years later or as stream of consciousness in the present (like Molly Bloom in Ulysses). But that would have been obnoxious and probably impossible to do well. A few of those bits made it into Frankie’s section where she’s listening to the people talk as they leave the party but that was as far as it went, thankfully.

Each of my books has had a crazy, ill-advised version I’ve either abandoned before writing or cut afterward. Originally Caveworld was 1,500 pages with 40-page transcriptions of phone conversations between the characters and a lot of drawn-out sex scenes and massive encyclopedic sections of California history and a whole interior book (an intentionally poorly-written supermarket pulp biography) about the writer Ed Distler but I wised up and cut it down to something like 350 or whatever it ended up at. (I think that version exists somewhere in my shelves. I should get rid of it.)

It’s like Bob Seger sang in “Against the Wind,” that bit about “What to leave in, what to leave out.” He also said he wished he didn’t know now what he didn’t know then. That’s good too. I walked past Bob Seger once on a street in Tokyo. He was literally three times the size of me. I think that’s an improper use of the word “literally” but that’s how big he was. He was a monster like Lou Ferrigno or Thomas Wolfe or Andre the Giant. My gut reaction was “Kill the monster!” Pitchforks, torches.

What’s the book you’re working on now?

I’ve been working on a longer novel for about two and a half years. I’m thinking it will be done, at least ready to edit, by the end of the year. Right now I’m kind of punching above my weight with it so it may take longer. Might do another slim book like Locust House and give it another couple years. It’s a very ambitious idea, this one, and maybe a bit too difficult for my current skills but I’m going for it and working hard every day.

As far as virtues go, the virtue in hard work is satisfying and strong and feels good at the end of the day. I want to get better with each new thing I release and with this one I’m hoping to take a giant leap forward. As cheesy and dated as this sounds, I want to write the Great American Novel and I’m going to get there or die trying. Of course I know I won’t actually die because of writing a book but I guess there are other kinds of deaths when you push yourself too far. Irrelevance, burn-out, loss of audience, loss of the essential perspective it takes to write truthfully, something like that. I don’t know if I’ll get where I want to go but I’m going to try like hell.